A cable car ascends to Tbilisi’s Narikala Fortress.

VOLANTE George Rush weathers Georgian hospitality and stumbles into intrigue as he mixes with everyone from a Nobel-nominated poet to Trump-haunted plutocrats

Photographed by the author

Above, from top: The controversial Peace Bridge spans the Kura River. Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, in Mtskheta, is said to house the robe of Christ.

The Chreli Abano bathhouse.

Above, from top: The controversial Peace Bridge spans the Kura River. Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, in Mtskheta, is said to house the robe of Christ.

The Chreli Abano bathhouse.

George Rush has contributed pieces to Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Wall Street Journal, Condé Nast Traveler, Men’s Journal, Departures, Travel & Leisure, and Spy, among others.

He is a guest contributor to Lucire.

I don’t know if the US State Department has ever issued a Travel Advisory about this but, if you’re considering a visit to the Republic of Georgia, be warned: its people will charm the pants off you.

Certainly, they’ll try.

For several years, a gentleman named Giorgi Rtskhiladze—a Georgian-born financier and music producer living in New York—would invite me through mutual friends to visit his homeland. Each time something got in the way and I had to send my regrets. What I didn’t realize, then, was that my trip was inevitable—because, for Georgians, hospitality is non-negotiable.

This time, Giorgi beckoned me to a vineyard that a 19th-century poet-prince had planted on an estate where Georgia’s current president and prime minister would be among the guests at a weekend of classical music and dance.

‘Stop,’ I said. ‘You had me at “vineyard.”’

Beyond being the 8,000-year-old wellspring of man’s winemaking, Georgia promised a dizzying array of landscapes: mountains with year-round snow, Black Sea beaches, subtropical forests, rolling hills—53 microclimates in all. Just as intriguing was the culture that had congealed at this Eurasian intersection. I’d read that Persians, Mongols, Turks, and Russians had all sought to control the Eden of the Caucasus.

I had not known that this land had also been darkened by the tangerine spectre of Donald Trump. Or that a suspicious hunting accident would figure into the trip. But we’ll get to that later.

Flying in through İstanbul, I met up with my old friend, author Tom Teicholz. On our first day, Tom and I toured Tbilisi, driving to the top of Sololaki hill, overlooking the capital. Below, autumn’s tinted trees shone like a coral reef. Around us, feral dogs stood guard on battlements dating to the fourth century. It’s said that Tbilisi (known until 1936 as Tiflis) has been destroyed and rebuilt 26 times. Its latest incarnation included Byzantine, brutalist, beaux-arts, art nouveau, neoclassical, and socialist classical structures, plus a few skyscrapers over 30 storeys tall. Surveying the city with us was Kartlis Deda, the ‘Mother of Georgia’, a 65 ft tall aluminum woman erected in 1958 to mark Tbilisi’s 1,500th anniversary. The hubcap-breasted lady held a mighty sword (to smote her nation’s enemies) and a welcoming goblet.

We strolled down cobblestone steps toward the city’s old quarter. Clinging to the hill were 19th-century wooden dwellings, painted like Easter eggs, with terracotta roofs and ornately carved balconies. The smell of sulphur smudged the air as we neared the hot springs that gave the city its name—tbili, or warm. Alexander Pushkin and Alexander Dumas were among the travellers who’d sweated in the Abanotubani District’s bath-houses—the prettiest being Chreli Abano, a mosaic-encrusted temple where a brawny man with a rough glove will scrub you for about €6.

Forgoing our exfoliation for now, we got back into our car for a spin through town. A statue of Lenin had loomed at Freedom Square until 1991, when protestors, declaring Georgia’s independence from the USSR, pulled it down. Following the bloodless Rose Revolution that ousted President Eduard Shevardnadze in 2003, a granite pillar rose, topped with a gilded statue of St George slaying a dragon (right). (I was tickled to find that half the men in Georgia share my name—well, until I got tired of turning around every time someone shouted, ‘George!’)

Forgoing our exfoliation for now, we got back into our car for a spin through town. A statue of Lenin had loomed at Freedom Square until 1991, when protestors, declaring Georgia’s independence from the USSR, pulled it down. Following the bloodless Rose Revolution that ousted President Eduard Shevardnadze in 2003, a granite pillar rose, topped with a gilded statue of St George slaying a dragon (right). (I was tickled to find that half the men in Georgia share my name—well, until I got tired of turning around every time someone shouted, ‘George!’)

Tooling down Rustaveli Avenue, I thought we’d taken a detour to Paris. The wide, leafy boulevard was lined with such grey eminences as the Georgian National Opera, the former Parliament building, and the Georgian National Museum. But Tbilisi is not an antique shop. Taking office in 2004, Georgia’s third president, Mikheil Saakashvili, hired cutting-edge architects, mostly Italian, to design daring public structures, including the House of Justice, the Prosecutor’s Office, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. I liked them but some griped that futurism was out of place in landmarked districts. Saakashvili brushed off his critics, who still sneer at the Peace Bridge he commissioned—comparing it to a sanitary napkin.

This isn’t to say that the city of nearly 1·5 million people doesn’t appreciate new ideas. Tbilisi buzzes with homegrown fashion boutiques, art galleries, and clubs (see article sidebar). Driving north along the Kura River, which bisects Tbilisi, we reached a banquet hall whose rambling grounds included scenic water features. Our guide—named George, of course—recalled once fishing a drunken Russian client out of the restaurant’s babbling brook. (The birthplace of Josef Stalin, Georgia had been the USSR’s playground and, despite an official chill, Russian tourists still flock here.)

George-the-guide took the liberty of ordering. We started with some khachapuri, a pillowy flatbread topped and stuffed with cheese. Naturally, we needed some khinkali, fist-sized steamed dumplings. George advised trying ‘city khinkali,’ filled with chopped beef, as well as ‘mountain khinkali,’ stuffed with mutton. The proper way to eat a khinkali, he explained, was to grab its pinwheel tuft, take a small bite to release its steam, and then gobble the rest whole. Leave the pinwheel, so you can count of how many you’ve had. Next came some obscenely long kebabs—served with a plum sauce and a savoury green pepper sauce. A bright plate of chopped greens was our nod to vegetables.

continued below

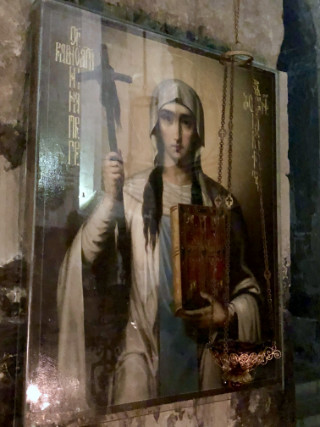

Left: Kartlis Deda, the 65 ft tall ‘Mother of Georgia’, watches over Tbilisi. Right: Portrait of St Nino, holding cross made of grapevines and her own hair.

We ordered some wine—a crisp white, which George said went well with toasts. And God forbid you eat without toasting. Illustrating, George volunteered to be the tamada, or toastmaster. ‘We have 82 toasts,’ he explained. ‘Allow me the to make the first—to our ancestors.’ A veteran of many supras (or feasts), George admitted that an evening of toasting can take its toll—especially if you’re using a traditional kantsi, or drinking horn, which forces you to finish your wine, lest it spill.

‘You learn some tricks for not getting too drunk,’ he said. ‘Like eating continually—particularly radishes.’

We concluded lunch with a snifter of Georgia’s other favourite spirit—chacha—a clear brandy distilled from grape skins and stems. Homemade chacha can burn like the devil’s aftershave. But this glassful was smooth, like aged grappa.

Stuffed and fuelled, we set out to plumb more of Georgia’s history in Mtskheta, 20 km north of Tbilisi. The capital of Georgia from the third century BC to AD the fifth century, Mtskheta boasts a number of UNESCO World Heritage monuments. Chief among them is the cross-domed Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, one of the holiest Georgian Orthodox sites. As a former Catholic altar boy, I’ve long been a student of the lives of the saints—especially their grisly relics. The cathedral did not disappoint.

There was the icon of St Nino, who’d brought Christianity to Georgia and, to this very town, a cross made of grapevines, bound with her own hair. There was the sculpture of an arm holding a chisel—modelled after the church’s architect, Arsukidze, whose limb a jealous king had lopped off. Most stunningly, the cathedral was said to house the robe torn from Jesus before his Crucifixion. According to legend, a Georgian Jew named Elias bought the garment from a Roman soldier and showed it to his sister, Sidonia, who died from emotion upon touching it. Sidonia’s skeleton is said to lie beneath the cathedral’s floor, still clutching Christ’s robe.

Having paid our respects to Sidonia and the ten Georgian kings who also rest at the cathedral, we drove back at dusk to our Tbilisi hotel, the Radisson Blu Iveria. Having started life in 1967 as a luxe lodge for Soviet bigwigs, the building became a vertical camp for 800 refugees fleeing the civil war in the region of Abkhazia. In 2004, President Saakashvili’s new government asked the refugees to check out (offering them US$7,000 per room). Radisson, and Georgia’s Silk Road Group reopened the refurbished hotel in 2009, installing Asian and Italian restaurants, an oxygen bar, and a casino.

continued below

Above, from top: Sunni and Shia Muslims worship side by side at Tbilisi’s Jumah Mosque. Entrance to the historic Chreli Abano bath house. Church of the Lurji Monastery.

Above, from top: Sunni and Shia Muslims worship side by side at Tbilisi’s Jumah Mosque. Entrance to the historic Chreli Abano bath house. Church of the Lurji Monastery.

I was just about to nap-test one of the hotel’s beds when my friend Tom called to say we’d been summoned to eat again. Dinner was across the street at Andropov’s Ears. The restaurant’s name was a wink at a monument erected on the site in 1983 to honour visiting Soviet dignitaries. At the time, people wondered what the monument’s curious concrete arches were supposed to represent. One Georgian wag suggested (probably not too loudly) that they must be the ever-eavesdropping ears of Communist General Secretary Uri Andropov. President Saakashvili ordered the monument destroyed in 2005. The Silk Road Group had replaced it with a glimmering building, topped with Tbilisi’s premier seafood restaurant.

Silk Road’s founder, George Ramishvili, a handsome, smooth-headed man, greeted us there. The son of two college professors, George, 51, started building his fortune by transporting commodities by rail through Central Asia during the chaotic days after the fall of the USSR. Silk Road, which supplied fuel to Joint Forces in Afghanistan, later ventured into real estate development, telecommunications, financial services, and energy. In 2005, George took an interest in the former estate of Prince Alexander Chavchavadze (1786–1846). Located in the village of Tsinandali, about 100 km northeast of Tbilisi, the nobleman’s summer mansion had once been a salon for artists and aristocrats but, in recent years, had fallen to ruin. George believed it should be revived as a cultural heritage site. Securing a 49-year-lease to the property from the government, Silk Road restored the prince’s Italianate villa and his English gardens. Oh, and his vineyards—for, besides being an acclaimed poet and conquering general (his godmother was Catherine the Great), Prince Chavchavadze had founded Georgia’s largest winery, the first to incorporate European technology.

By 2016, 100,000 people a year were visiting Tsinandali. George Ramishvili wanted to build a hotel to accommodate them. He also wanted to give them classical music to listen to. For the hotel, he turned to his partners at Radisson. For the music, he enlisted Martin Engstroem and Avi Shoshani, co-founders of Switzerland’s Verbier Festival. The two men, who were dining with us, have been luring classical giants to the Alpine village for the past 25 years.

You’d think that a classical music festival would be an easy sell. But George, who needed government approval, ran into resistance. Part of the rub was his partner—Yerkin Tatishev, a doctor’s son who’d also capitalized on the rupture of the USSR by buying stakes in de-nationalized mines and factories in his native Kazakhstan.

Yerkin, who also was at our table, recalled, ‘Some Georgians were asking, “Why is this Kazakh guy involved?”’

A muscular man with a newsboy cap and a tireless smile, he recalled the day George first brought him to Tsinandali.

‘The place needed a lot of work,’ he told me. ‘But its energy was so great. From that day, we started dreaming. We just wanted to save the place. But some people didn’t believe a private enterprise should operate a national treasure.’

George and Yerkin decided to go to church. But they didn’t just pray for approval. They sought the opinion of Georgian Orthodox Patriarch Ilia II. After listening to their pitch, the Patriarch found their motives pure and, in a televised statement, blessed their Tsinandali dream. In short order, the government pledged US$5 million to the project.

‘It took one year to convince the government that we are good guys – that we weren’t interested in making money,’ said Yerkin. ‘Once we had the Patriarch on our side, good people started to join us.’

Listening to the stories of these guys, I liked them. Dressed in jeans and sneakers, they didn’t look like oligarchs. Their commitment to Tsinandali seemed sincere.

But then, after we’d all said good night, I headed back to our hotel. I figured I’d catch up on some articles on Georgia. One was a long New Yorker story titled, ‘Trump’s Business of Corruption’. In it, journalist Adam Davidson told how George Ramishvili, my dinner host, and Giorgi Rtskhiladze, the New York guy who’d invited me to Georgia, had wooed Donald Trump to come in on a deal to build a 47-storey condo tower in Batumi, a resort city on the Black Sea. The Georgians had to hondle for a while with Trump lawyer Michael Cohen but, in 2011, Trump finally accepted the Silk Road Group’s offer of US$1 million—just for bestowing his name on the tower. Courted by President Saakashvili, Trump had come to Georgia in 2012, claiming he would invest millions in the country. But after he’d won the US presidency in 2016, he’d bailed out of the project, saying it would pose conflicts of interest.

Having reported on Trump since the 1980s, I’ll confess I’m not a fan. It troubled me that my hosts had been in bed with him. Then again, Trump had gulled many decent people—Trump University students, contractors he’d stiffed, millions of American voters. Foreign developers had long been susceptible to his brassy conception of ‘classy’. Georgian billionaire and former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili told The Atlantic that, contrary to reports. ‘Not a single cent has been invested by Trump [in Georgia]. It’s a complete lie.’ So I allowed that Silk Road wasn’t alone in falling for Trump’s spiel. More concerning was The New Yorker’s contention that they may have been in league with a world-class embezzler.

It’s a Gordian story. But, briefly, in 2005, Kazakhstan’s BTA Bank loaned about US$300 million dollars to the Silk Road Group. By 2009, faced with nationalization of his bank, bta chairman Mukhtar Ablyazov fled Kazakhstan for the UK. A Kazakh court later convicted Ablyazov in absentia of stealing US$7,500 million—via un-recouped BTA loans to specious projects. In his story, Adam Davidson attempts to make the case that the BTA loan to Silk Road were part of the boondoggle. And that Trump must have known about it. Among the culprits, in Davidson’s mind, was my dinner companion, Yerkin Tatishev. He’d once been deputy chairman of BTA—at the same time, Davidson alleged, that he was a “secret partner” in the Silk Road Group.

The story lacked a gun that truly smoked, relying on undated emails and speculation by money-laundering experts. In the article, George and Yerkin and Giorgi vigorously denied any self-dealing or wrongdoing. But why then had Silk Road agreed to a US$50 million settlement with the Kazakh government?

![]() Top: Tsinandali Festival co-founders George Ramishvili and Yerkin Tatishev. Left: The author’s host, Giorgi Rtskhiladze. Above: Nobel-nominated poet Dato Magradze.

Top: Tsinandali Festival co-founders George Ramishvili and Yerkin Tatishev. Left: The author’s host, Giorgi Rtskhiladze. Above: Nobel-nominated poet Dato Magradze.

Need to know

Tsinandali Festival

The latest from Tbilisi

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Making excuses on the road in Madagascar

George Rush has had a long-time fascination for Madagascar, finally venturing there to discover the nature and culture of the isolated island nation

Photographed by the author

Errands for the soul

Stanley Moss heads back to Varanasi, then to Amritsar and Dharamshala, where they were granted an audience with HH the Dalai Lama

Photographed by the author; audience photographs by the office of HHDL

Delirious Dubrovnik

Stanley Moss finds a gem on the peninsula near Dubrovnik, a discreet, deluxe hotel with first-class food in a personal, authentic setting

Photographed by Paula Sweet

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.