LIVING With a web-savvy generation who know about Big Tech’s issues with privacy and surveillance, print magazines are looking like a great time-out from digital screens at every moment of the day. Jack Yan looks at the trends

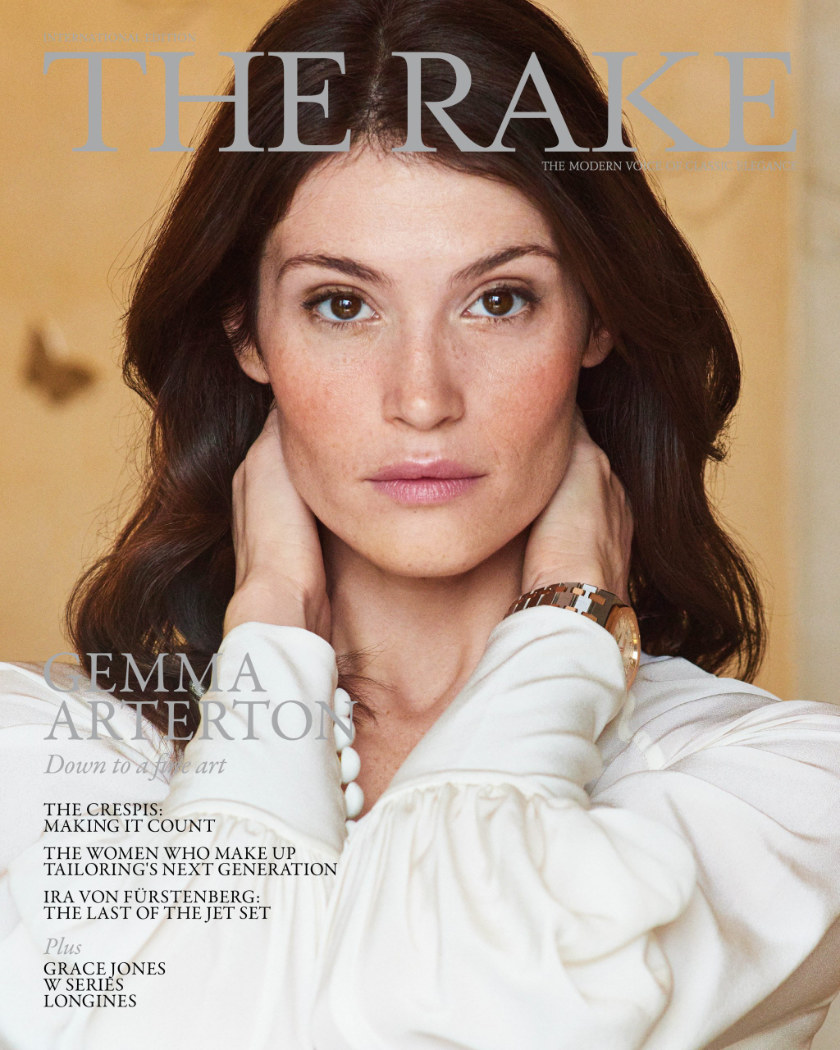

Independent magazines: Lucire in the header image; The Rake featuring Gemma Arterton;

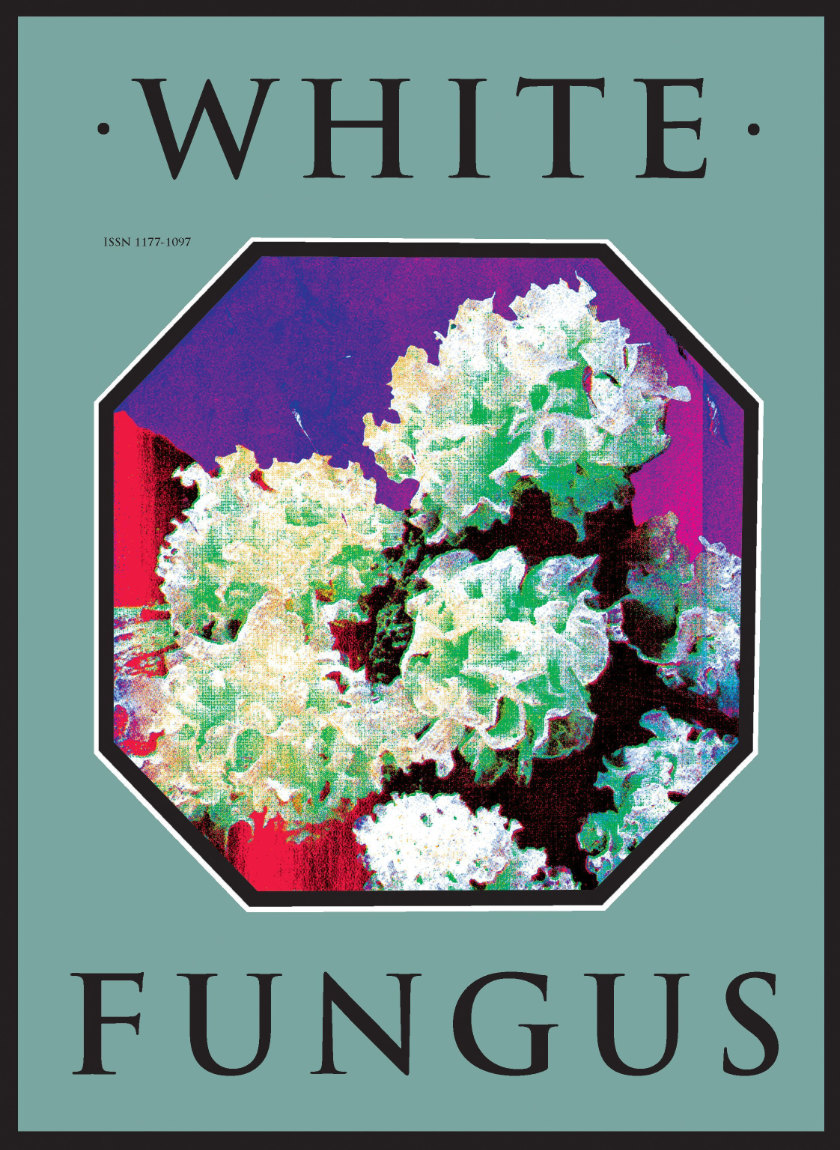

White Fungus of Taiwan; and Eye from the UK.

Independent magazines: Lucire in the header image; The Rake featuring Gemma Arterton;

White Fungus of Taiwan; and Eye from the UK.

Jack Yan is founder and publisher of Lucire.

For years, Big Tech, and more specifically, Google and Facebook, have been telling us how engaging their platforms are. We read headlines in many countries about the necessity of placating these two platforms, tailoring content to suit their algorithms. The entire country of Australia was locked in a battle with them in early 2021, demanding that they pay traditional publishers whose revenues had been decimated by them, to the extent that Facebook, in an own goal, demonstrated its dictatorial bent by not allowing Australian news outlets to be shared on the platform (in its usual clumsiness, however, it also knocked out its own official page to Australians).

There are, of course, statistics that back up how Big Tech’s monopolistic powers have hurt many publishers. Online publishing, for instance, is not a game that earns much money: advertising space that went for US$75 CPM (cost per thousand exposures) before the turn of the century now sells through Google at fractions of a cent, while Facebook has absorbed plenty of spending through being able to finely target audiences. A lot of local community newspapers have shut as people seek their news through their cellphones. What is harder to find, however, is whether digital is even an engaging, effective medium, and what the trends show with regard to people’s preferences between print and digital.

We have long maintained, sincerely and without any hidden agenda, that a lot of the numbers can’t be backed up. As early as 2013, Bob Hoffman, a retired advertising agency chairman, alleged that half or more of paid display advertisements online are never even seen by people, yet the clients are charged for them. This is a space in which Google, which controls the occidental online ad space, makes the overwhelming majority of its money. Hoffman has remained critical of the US giant. Facebook, meanwhile, has no independent verification of its advertising results, according to Hoffman, and is currently being sued for allegedly providing false data about reach. We can confirm that a large number of reported bots are allowed to remain on the platform, and they become part of the “audience” that likely receives advertising, leading to wasted spends. As noted recently in this publication, just under half of all Instagram accounts are fake, with the same outcome of wasting advertising spends. Instagram is owned by Facebook.

It’s not just the commercial aspects of Big Tech that are flawed. Young people, many of whom have grown up in a world where being wired 24–7 is the norm, are beginning to show an interest in print magazines, since they have begun to find that the too-regular advertising (including ads that obscure parts of, if not all of, the page, especially on a small cellphone screen), auto-play videos, tracking, and other techniques used by online ad networks annoying. It’s similar to an American University study in 2016 that showed 92 per cent of young people preferred books to an e-book reader, especially with the high price of the reader units. Another study we saw from YouthSight in 2015 had 64 per cent favouring print and 16 the e-book. Statistically, readers engaged with a print story more than with a web one.

Just as with any other age group, they’ve found that being wired all the time is tiresome, and recognize that being offline is a valuable opportunity to unwind and get some detox from their digital world. They have plenty of pursuits, and actually read more than previous generations. There is enjoyment, then, to long-form journalism, to features that do not date quickly, and to being captured by great visuals. There is the tactile nature of the magazine, which can be kept as a souvenir, especially a special issue that might feature a celebrity or mark a major event.

Magazines, in particular independent ones, which are enjoying the custom of younger audiences, are the antithesis of clickbait news sites; one might even refer to them, as Walker Lötscher of Inside Hook did, as ‘slow journalism’.

Importantly, because young people are digital natives, who don’t know a world without online publications, they have become knowledgeable about phenomena such as fake news or deepfake videos. (Similar words were once said about the generation before, who could detect deceptive advertising, having grown up in a world of mass marketing.) Many are wise enough to know that social media cannot be relied upon, and, according to a Ypulse study, their trust in magazines is twice as high—69 per cent, versus 34 per cent.

Being part of their generation, they know how easy it is for someone to set up a blog or a social media presence, so the traditional press comes into its own once more, especially if they have both print and online presences. They realize there is a difference between amateur blogs and professional publications, something that wasn’t always obvious to earlier generations.

In 2017, the Financial Times noted that Slack, the independent magazine distribution service, recorded a 32 per cent growth in subscribers (three years earlier it had been as high as 76 per cent).

In 2018, The New York Times reported on the rise of independent magazines among younger readers. These were described as ‘small, sophisticated … produced on a shoestring by young editors with strong points of view and a passion for their subjects’, beautifully designed and costing upwards of US$20 per issue. Their description of lavish design and exclusivity almost sounds like this title, and our approach of producing a ‘soft-cover coffee-table book’, as the author has put it on many occasions, gives an indication of where magazines are heading. We simply arrived there very early.

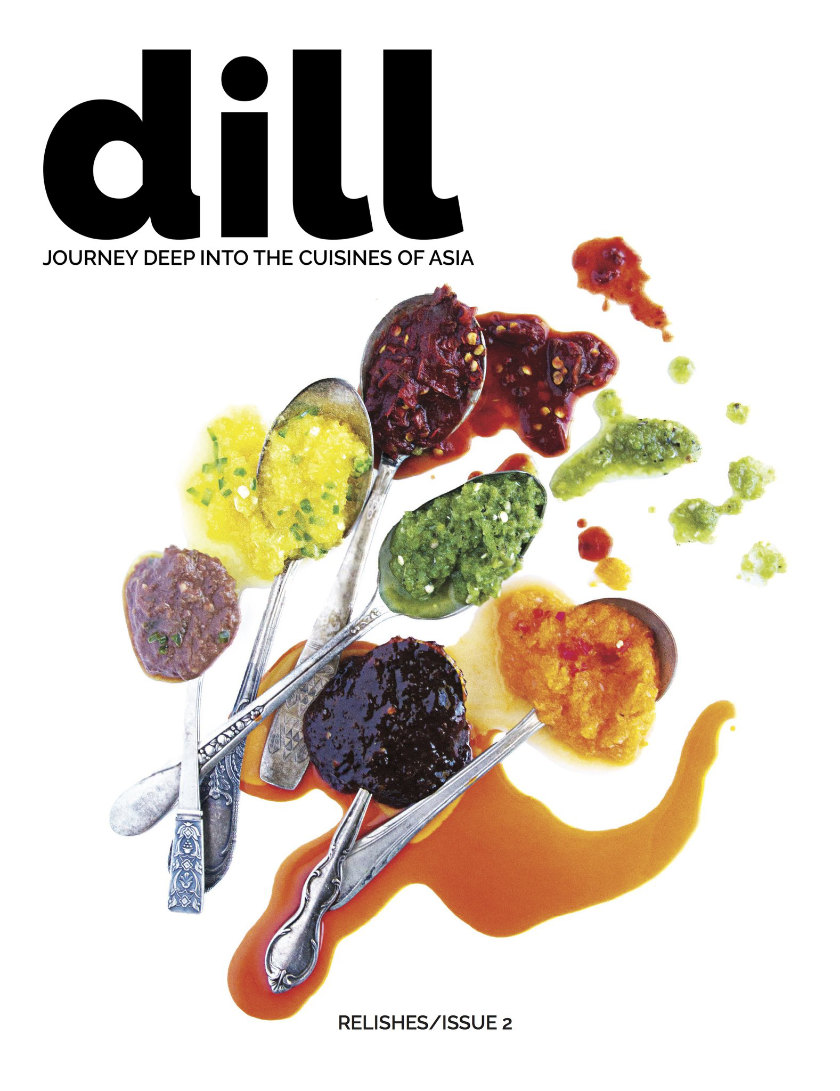

The American indies, they continue, tend to be staffed by one or two people, finding favour with younger audiences. The New York Times noted that independent print publishers in the food category were finding an increasing reader base among younger people, with titles such as Dill and Mold. The former was created by a student at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign who believed Asian cuisine could be covered more authentically and respectfully. Mold looks at the future of food, our inability to feed the entire planet by 2050 if we don’t change our consumption habits, an issue that is gaining more traction in related circles.

But we know of many others, not always created by young editors, but certainly appealing to similar markets, piquing the interests of young people who want to get a unique take that’s not reflected by the mainstream. There is White Fungus in Taiwan, an art magazine founded by Ron Hanson, an expatriate New Zealander, that enjoys a strong following. Hanson and his team cover not just visual art, but sound art, as well as history, culture, and poetry.

Men’s fashion magazine The Rake, which has managed to find distribution far beyond its London HQ, might commit the sin of too-small body type, but its features, which, like Lucire’s have an appreciation of history and context, leave you feeling more knowledgeable—surely this is something that all magazines should achieve? The Rake sees the sartorial archetype as Cary Grant, presumably the later one of North by Northwest and Charade, and revels in its jet-set world, right down to foiled type on its covers.

Some are well established and thick with content, such as France’s Cahiers du Cinéma, covering film with an European, artistic lens, not letting Hollywood blockbusters dominate the bulk of its pages; unfortunately with its sale last year and the resignation of its entire editorial staff I haven’t seen new issues or been able to make a judgement about its ongoing independence. Staying with the subject is Another Gaze, which has published, on average, an issue a year, with unique content not found elsewhere, taking a critical view through feminist film theory.

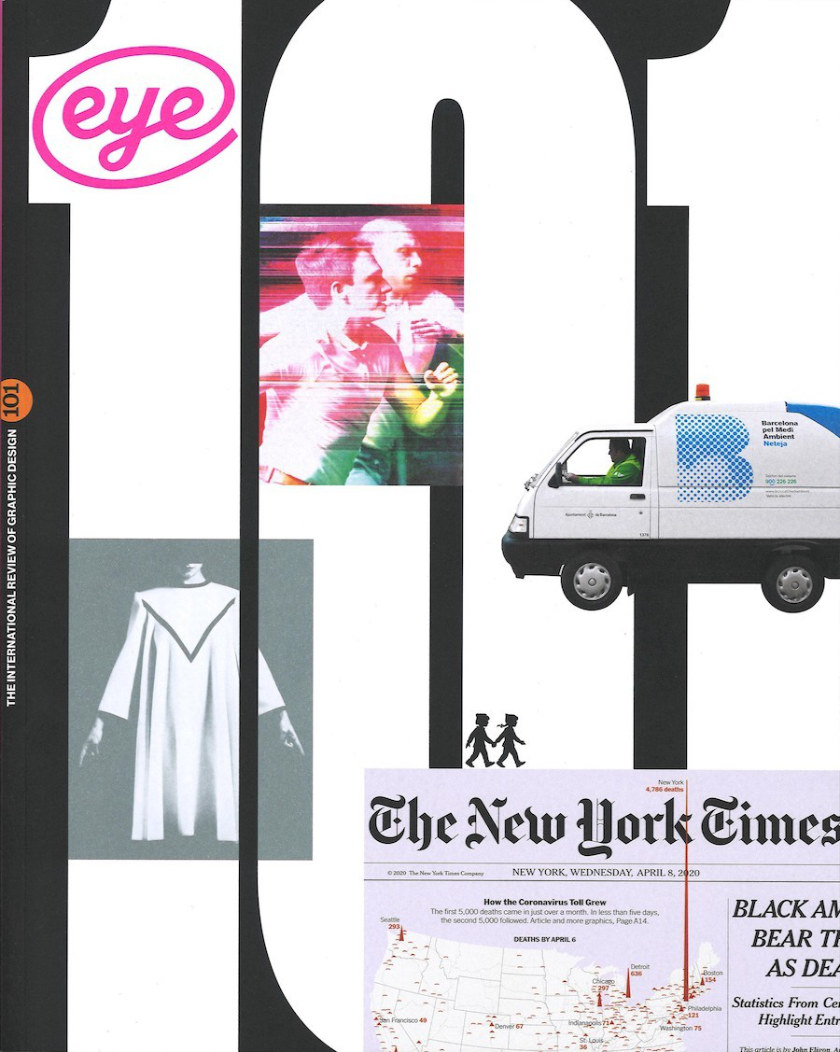

Many years ago this author penned a piece for Eye, commissioned by its editor John Walters, on typography; this British graphic design quarterly is another title that takes a deep look at its subject, and, given its audience, laid out to the highest standards.

The best approach appears to be maintaining both print and online presences; branching out into events and television also make sense if they can be sustained. The Americans call the approach ‘omnimedia’; we prefer to think of it as ‘cross-media’. You need as many as possible to work side by side. Terminology aside, how confident are we that the 2020s might see a renaissance in print, especially among younger readers?

The short answer is that we’re reasonably confident, as the Zeitgeist shifts away from what were once the darlings of Silicon Valley. This magazine was one of the first to predict the rise of the social media influencer, and a few years ago, we predicted their fall. This is only now beginning to play out with some questioning the reach numbers of all but the bona fide celebrities. Of course we need to be aware of the environmental impact of predicting the renaissance of print; digital was supposed to bypass the felling of trees for print publishing. But the first coming of the web hasn’t turned out that ideally, disappointing even its inventor, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. He has warned against the corporatization and divisiveness that have infected his invention. With few governments taking on Big Tech, and with Big Tech unwilling or incapable of cleaning up its act when it comes to fake news or conspiracy groups, it’s easy to see how it would be unappealing to use them. Magazines, then, transport us to the worlds of our choice, untracked and offline, knowledgeable and, depending on the sector, hopefully apolitical. •

Independent magazines Dill and Mold, two independent titles from the US. Cahiers du Cinéma, which lost its editorial staff last year. Another Gaze, considering film from feminist theory.

Independent magazines Dill and Mold, two independent titles from the US. Cahiers du Cinéma, which lost its editorial staff last year. Another Gaze, considering film from feminist theory.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Where have the fun fashion magazine websites gone?

Removing the design and content review scores from Lucire’s link section is the result of much larger forces in publishing and technology, as Jack Yan explains

Blogs are good for fashion, as long as we can find them

Blogs are good for fashion, as long as we can find them

Some of the top fashion blogs are good for the industry, and in coming years, the vanity-driven, poorly written ones may disappear as social networks grow, writes Jack Yan

Hack Is Back

Hack Is Back

After a successful serialization of travel editor Stanley Moss’s novel, The Hacker, earlier this year during lockdown in many countries, we follow up with its sequel, Hack Is Back, which picks up immediately after the conclusion of the earlier story about a young technology company located in Gurgaon, and continues to follow the lives and adventures of all the cast members. This time they’re mixed up with Israeli cybercriminals, Bitcoin ransoms and malware on smartphones

Who’s who | Chapters 1–3 | 4–7 | 8–11 | 12–15 | 16–19 | 20–3 | Acknowledgements

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.