BEAUTY In one of our favourite beauty stories of the last 20 years, Geneviève Hole headed to Grasse to uncover the evolution of perfumes, and found that among all the commercialism are a handful of parfumeries creating distinctive, rare scents

From issue 29 of Lucire

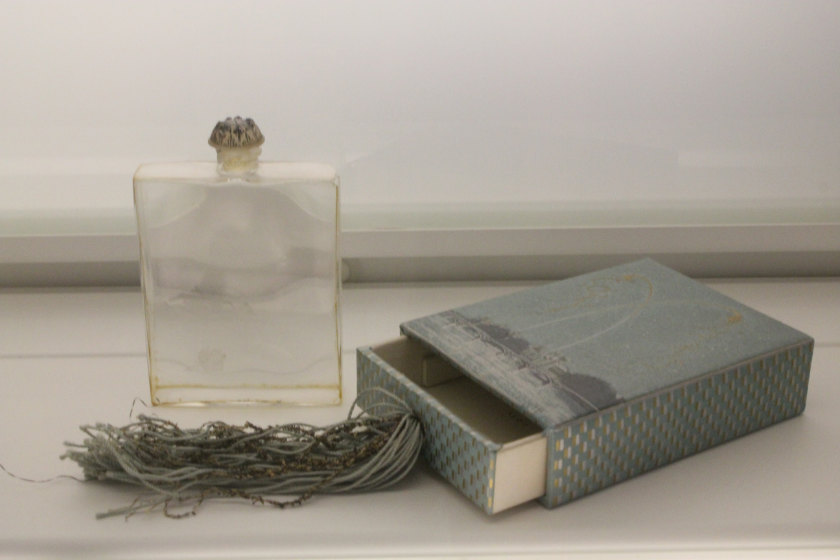

History Exhibits at the Musée

international de la parfumerie

in Grasse.

History Exhibits at the Musée

international de la parfumerie

in Grasse.

Geneviève Hole is a writer for Lucire.

I’ve been obsessed with perfumes for quite some time.

One of my fondest childhood memories is a holiday in the south of France. I must have been about nine. I loved the beaches and the food but I have a clear and particularly fond memory of visiting a perfume museum in Grasse.

I recall walking through a greenhouse that was home to all sorts of plants used for their fragrant oils and smelling what must have been hundreds of solid perfumes, much to the dismay of my tired parents who waited patiently for me, hanging out for the next café and Perrier.

And then there was my first perfume, a present from my father—Baby Rose Jeans by Versace. I don’t think I ever finished it, the particu-larly sickly sweet scent which was apparently a ‘subtle blend of mandarin, violet, sandalwood and vanilla’—subtle, Versace? Come on! Anyway it did make me feel extremely mature at the tender age of 10. Yes, I was a perfume wearer, and Versace at that.

Thinking back at my love affair with perfumes, the interplay between the actual scent and the label to me is a very interesting space. If my 10-year-old self was conscious enough to know it meant something to be wearing Versace, it needs to be asked: when did we get so obsessed with fashion house fragrances?

Being based in the south of France it quickly became obvious how I was to go about answering this question. I had to return to Grasse, to repeat the perfume pilgrimage I had taken years ago.

Grasse is a little town situated about 20 km from Cannes. The climate has long since made it an ideal place for growing fragrant plants and flowers, but Grasse got its name as the perfume capital of the world in the late 19th century. Using discoveries made in the industrial revolution such as steam distillation and the production of fragrant synthetic materials, the perfume industry of Grasse boomed and contributed to the rapid expansion of the town.

Perfume is still a major industry for the town with all sorts of perfume plants grown in Grasse including rose, jasmine and tuberose. Flowers are picked every day from May through mid-October, with pickers starting at dawn and working until mid-afternoon. Paid-by-weight pickers can collect between five and eight kilograms of petals an hour.

The town is home to a number of French perfume houses and perfume museums, the most famous of which is the International Perfume Museum (Musée international de la parfumerie). This houses both permanent and temporary exhibitions covering over 3,000 years of perfume history—clearly the ideal place to learn more about the history of fashion house fragrances!

Throughout the ages, wearing perfume has been as much about smelling good as not smelling bad. During the Age of Enlightenment, masking bad smells (both on the body and within the home) and attempts to ward off airborne diseases were major reasons behind the widespread use of perfumes. However, perfume was not destined to stay as just a Band-Aid covering up horrid smells. At the turn of the 17th and 18th century, both perfume and clothing became used as tools of seduction. Increasingly complex bottles became worn as jewellery, and bottle pendants worn on the body became fashionable. Distinguishing one’s self with fragrance—a sign of one’s personality—became as important as warding off foul smells.

Fashion house fragrances as we know them today are inextricably linked to marketing and this phenomenon comes from a more recent period in history: the 20th century.

Something all perfume-lovers will know is the distinction between a simple and a complex fragrance. A simple uses its name to describe how it will smell such as orange blossom, violet and jasmine water—symbols of traditional perfumery with a single floral note. A complex fragrance has a combination of fragrances and has an abstract name, one that no longer evokes the ingredients within but calls on the collective wealth of imagery. Suddenly it is a compelling name must attract a customer, rather than the known promise of a particular single smell.

Single floral scents were popular at the beginning of the 20th century, but this all changed thanks to Gabrielle Chanel. Chanel was the first company to pioneer a complex fragrance for the modern woman. Previously, the only women who had worn a fragrance with more than a single floral note were “women of the night” and Chanel took it upon herself to create a new, dynamic scent that wouldn’t be associated with the musky fragrances worn by prostitutes.

But Chanel wasn’t the first couturier to turn to perfume. In 1911, Paul Poiret is responsible for making perfume an integral part of female attire with his brand Les Parfums de Rosine. The Callot sisters, Chanel, Lavin and Patou closely followed. Gradually, and even more so after World War II, traditional perfume houses faced stiff competition from fashion and jewellery houses.

Marketing and the media had a major part to play the success of fashion house fragrances. A commercial revolution ran in parallel with the Industrial Revolution and the 20th century saw the birth of mass media, which changed the way we learned about fragrances. For example, word of mouth spread the wonders of No. 5 to the élite and the cognoscenti when it was first launched in 1921, but mass media eventually introduced it to a much wider market, with the first solo advertisement of Chanel No. 5 placed in The New York Times on June 10, 1934.

Like perfume, branding as been around for quite some time. As far back as 1300 BC, potter’s marks were used on pottery and porcelain in China, Greece, Roma and India and the branding of cattle and livestock go back as far as 2000 BC. In a modern sense, branding emerged as a significant area of emphasis for companies and their products in the late 1980s and 1990s. The brand and all it stood for played a big role transforming consumers’ interest in fashion house fragrances to an obsession. Couture brands symbolized luxury. Luxury, which to most, is unattainable except when it comes to perfume. Since it is comparatively affordable, it represents the first step towards luxury for those who can’t afford a designer dress or jewellery.

continued below

Above, from top: Bottles at the Musée

international de la parfumerie. Lolita by Paul Brecher of

Pontoine, Paris.

Arôme Divin de Rallet, 1925.

The International Perfume Museum featured a timeline of fragrances launched through the 20th century, which was a fascinating visual display of how our tastes have changed over the last hundred years. It did, however, leave me feeling a little disappointed. After gazing at literally hundreds of intricate perfume bottles from the from ancient times right through to the early 20th century, I felt a sense of sadness at what perfume has become in our day and age. Gone are the bottles that look real like works of art made from quality materials featuring ornate atomizers. Gone is the quant, feminine, French sentiment. Instead there seemed to be an abundance of all that heralds commercial success—gaudy colours, bling, celebrities and sex. Commercially successful perfumes essentially reflect what consumers want (or think they want) which indicates that most people (unfortunately) like perfumes with trashy names endorsed by celebrities in oversexualized ads. But I like to believe that there are others out there who, like myself, long for a high quality, unique fragrance, something different to CK, Gucci or Prada.

Fortunately, the museum included an excellent temporary exhibition on the major perfume treads that have marked in the 21st century so far. This exhibition featured many fashion house fragrances but also fragrances by labels previously unknown to me, such as Kilian (an eco-luxe perfume brand from Paris, the brainchild of Kilian Hennessy), Frédéric Malle (determined to liberate perfumers from the kinds of restraints often imposed by marketers and focus groups), Juliette Has a Gun (created and designed by Romano Ricci, who approaches perfume as art), and Francis Kurkdjian (artist turned perfumer), which greatly boosted my spirits. Finally, we were applauding modern-day perfume artisans who are producing truly inimitable fragrances.

All in all, the perfume pilgrimage was a success, and my visit to the International Perfume Museum was as enjoyable as when I was 10 (for different reasons perhaps!). And my final word on fashion house fragrances: evidence suggests they won’t be going anywhere soon, but never fear. With a little bit of effort to get off the beaten track (and out of duty-free) you’re likely to find a much wider selection of special boutique fragrances that you’d imagine. •

Scent-ral bank

Which parfumeries eschew crass commercialism in favour of high quality? Geneviève Hole chooses her four

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

A guide to 2017 beauty

In our second part on 2017 débutantes, Lola Cristall examines beauty products and services that aim to make life better and more indulgent

Scent and sensibility of a woman

Scent and sensibility of a woman

Fortune 500 headhunter-turned-perfumer Nicole Mather followed her nose and found her passion, and inspires Elyse Glickman to trust her senses in finding lasting success

Empire of the jade

Empire of the jade

Fashion designer Agatha Brown has been creating some of the industry’s most unforgettable fragrances in the last few years

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.