Above: The Tsinandali Estate.

Above, from top:

A statue of poet Giorgi Leonidze watches over Tbilisi’s 9th of April Park.

Prince Alexander’s country house. The ruins of Gremi afford a kingly view of the Kakheti landscape. The snowy Caucasus loom over the Tsinandali Festival’s outdoor stage.

Above, from top:

A statue of poet Giorgi Leonidze watches over Tbilisi’s 9th of April Park.

Prince Alexander’s country house. The ruins of Gremi afford a kingly view of the Kakheti landscape. The snowy Caucasus loom over the Tsinandali Festival’s outdoor stage.

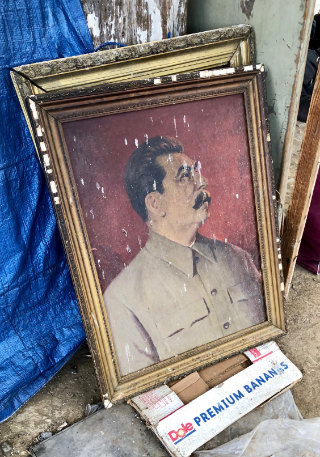

The next morning, I headed out on an early run around Tbilisi. The bars, casinos, and strip clubs looked exhausted after another night of dutiful abandon. But, in the shallot-domed church of the Lurji Monastery, the prayerful were already lighting candles. Dealers at the Dry Bridge flea market, near the river, were laying out their dusty treasures. Lining the sidewalks were scimitars, gas masks, forceps, holy icons, military medals, antlers, chandeliers, bearskins, typewriters, and busts of Stalin and Lenin. Intriguing contemporary paintings hung under the bridge. Some dealers used their venerable Soviet-made cars as mobile shops—stacking the squat Ladas with Victrolas, Smith–Coronas, samovars, and nesting dolls.

continued below

Above: Dealers at the Dry Bridge flea-market hawk remnants of Georgia’s past.

Above: Dealers at the Dry Bridge flea-market hawk remnants of Georgia’s past.

I bought a fistful of yellowed Soviet rubles and Georgian lari, then jogged back to the Radisson. After a quick shower, I joined the assembled delegation of music, wine, and human rights’ activists climbing into a convoy of sedans bound for Tsinandali. My pal Tom and I shared a car. Tom still cherished the memory of the Israeli Symphony Orchestra performance Zubin Mehta had conducted the year before at a soft opening of Tsinandali’s theatres. Together, we made our way on twisty route 383 as it climbed through tawny meadows and saffron forests.

Past the Gombori Pass, the snowy Caucasus came into sight. Our 90-minute drive ended at the Tsinandali Estate. Its centrepiece was Prince Alexander’s country house, built in 1835. Anti-tsarist followers of Imam Shamil had nearly destroyed the mansion in 1854. Meticulously restored, the house now featured furniture and heirlooms donated by the prince’s descendants. Surrounding the villa were 18 hectares of landscaped gardens.

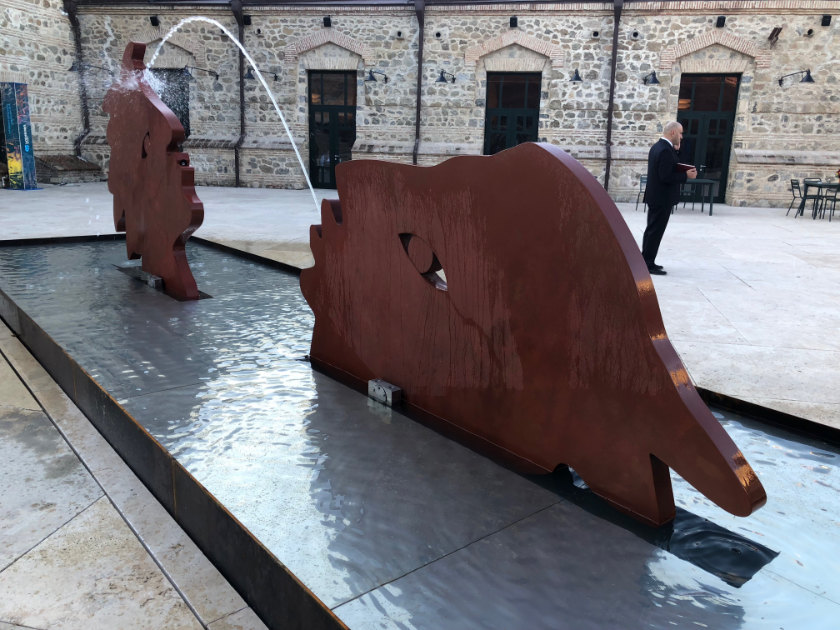

A short distance from the villa stood a 141-room Radisson Blu hotel that, with our arrival, had officially opened. Designed by Septiembre Arquitectura and Ingo Maurer, the five-storey building’s boxiness was softened by trellises dripping with ivy. The hotel looked like a giant Chia pet. Descending its grand outdoor stairway, I found a courtyard where guests had gathered around a whimsical fountain whose two oscillating cast iron heads spit water at each other. I assumed it was water. The crisp air was flecked with the tongues of Britain, France, Japan, America, Russia, and assorted former Soviet republics. A trio of Georgian Orthodox prelates sported black vestments, gold crosses, white beards, and sunglasses. They looked like an ecclesiastical ZZ Top. Georgia’s prime minister Mamuka Bakhtadze and president Giorgi Margvelashvili stepped up to the microphone to salute the public-private partnership that made the complex possible. Bakhtadze and Sharon Prince, president of the US non-profit Grace Farms, signed a resolution against human trafficking. Then a trio of young musicians demonstrated the superb acoustics of the new Chamber Concert Hall with a lovely Mendelssohn recital.

continued below

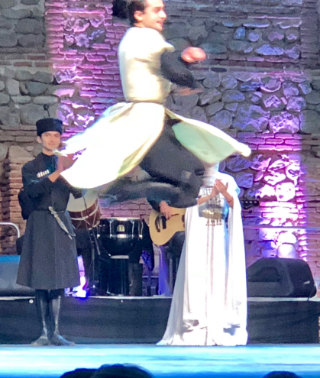

Top row: Kazakh guests and Georgian Orthodox prelates celebrate the Tsinandali Festival launch. Above: Dancers from the Sukhishvili Georgian National Ballet company show their versatility during folk performance and at EDM after-party.

Top row: Kazakh guests and Georgian Orthodox prelates celebrate the Tsinandali Festival launch. Above: Dancers from the Sukhishvili Georgian National Ballet company show their versatility during folk performance and at EDM after-party.

Afterward, we migrated to a building that had once been part of the estate’s winery. Laid before us was a buffet of kuchmachi (chicken livers with pomegranate), badrijani nigvzit (roasted eggplant stuffed with walnut and garlic paste), pkhali (minced wild greens), mtsvadi (brochettes), and satsivi (a version of stroganoff), to name a few of the entrées.

Tom and I foraged through it all. We were still grazing when a waiter’s bell summoned us to an outdoor amphitheatre. We were supplied with blankets and small bottles of chacha to ward off the cold. On stage was another heat source: the Sukhishvili Georgian National Ballet company. Sparks flew from the clashing swords of gyrating Cossacks. Tiaraed ballerinas stepped so quickly beneath their gowns that they appeared to be gliding on wheels.

All this would have been enough for me. But it was time to eat again. We were ushered into a ballroom, where circling waiters strafed us with plates. A troupe of folk singers launched into Georgia’s unique style of polyphony, built on a harmonic structure of parallel fifths and calculated dissonances.

I spotted Giorgi Rtskhiladze, the New York-based Georgian who’d invited me.

‘I’m glad you could finally see my country!’ said the dashing former pop singer (once known to his fans as King George). He administered a bracing Georgian hug.

Such an occasion naturally demanded toasts.

Lifting his glass, Yerkin declared, ‘We have a saying in Kazakhstan: “Grief becomes one thousand times less when we are together. And joy becomes one thousand times greater!”’

After dessert, some of the polyphonic singers gathered around the piano of jazz prodigy Beka Gochiashvili for some saloon-style improvisation. Those of us who could still stand waddled back to the old winery. A DJ from Berlin was rewiring the mood, pumping electronica into the now-off-duty ballerinas, who came alive like Fritz Lang’s beguiling robot in Metropolis.

Nearby, a pane of Plexiglas in the floor let you glimpse the cellar oenothèque of Prince Alexander. Its 1,800 bottles, dating to 1814, included vintages from Chateau Lafitte, Chateau d’Yquem, and other fabled domaines.

I found it amazing that such a trove had survived almost two centuries—including the period when the estate was a retreat for Soviet officers.

‘During all these years, the people who lived here watched over it,’ George Ramishvili told me. ‘Old women took care of the bottles. But more than that, I think, everyone, even in the Soviet era, respected that this was our national patrimony.’

I’d been looking at George and Yerkin differently since reading that New Yorker story. I felt conflicted. It was hard to reconcile the article’s sinister portrait with these men who supported the arts, who opposed human trafficking, and who’d paid my passage. With techno throbbing in our ears, this wasn’t the ideal place to delve into the allegations. But, having had a few glasses of chacha, I felt compelled to tell George that he was better off without Trump.

‘Trump is such a politicized word that you don’t really want it attached to your property,’ I shouted. I also declaimed that, since Trump had pulled out of the luxury tower deal, he should return the US$1 million Silk Road had paid him.

Ramishvili listened to my gratuitous advice and kept his comments brief. He said the Trump-free property, now known as the Silk Tower, ‘is starting construction in February [2019]. All is going well.’ Then he smiled and politely took his leave.

continued below

Above, from top: Tamara Kvesitadze’s fountain sculpture anchors the courtyard of Tsinandali’s Radisson Collection Hotel.

The villa of Prince Alexander Chavchavadze, now a museum Qvevri jars at the Tsinandali Estate vineyard.

Above, from top: Tamara Kvesitadze’s fountain sculpture anchors the courtyard of Tsinandali’s Radisson Collection Hotel.

The villa of Prince Alexander Chavchavadze, now a museum Qvevri jars at the Tsinandali Estate vineyard.

Tom and I joined some other guests on a jitney tour of the area the next morning. Rolling past groves of walnut trees, we crossed the Alazani River. At the ruins of Gremi, the former capital of the Kingdom of Kakheti, I climbed the steps of king Levan’s 16th-century citadel. It afforded a magnificent view—not only of the countryside, but of the king’s clammy-looking stone toilet. We moved on to the 11th-century Alaverdi Monastery, which remains an active fortress of faith. Its towering cathedral cast a shadow over acres of vines that still filled priests’ chalices.

Winemaking in Georgia goes way back. Shards of pottery, embellished with grapes, time-stamp man’s first stab at viticulture here around 5980 BC. Since then, Georgians have remained pretty happy with natural distillation—letting grapes and skins ferment without added yeast in clay jars, called qvevris, that are stored underground. I saw some of these hulking vessels strewn on the front lawn of the Tsinandali Estate vineyards, where we pulled up at the end of our jaunt. The Tsinandali wine-works produces qvevri vintages. But being the place where Prince Alexander introduced European methods in 1841, the revitalized estate also sported gleaming presses, filters, and copper distillation stills.

Over 500 varieties of grapes are native to Georgia. The Soviets squelched most of them, ordering growers to churn out cheap wine for the masses. But many varieties are back. About 40 are commercially grown, and blended into roughly 45 cuvées. The Tsinandali Estate uses 11 grape varieties. Idling on the porch of its warehouse, we sampled Nino Veuve Griboyedoff, an elegant semi-dry rosé extracted from Aleksandrouli and Mujuretuli grapes. Saperavi, plumy red, came semi-sweet and dry. Khikhvi, an amber qvevri wine, had an earthy whisper of its terracotta incubation.

In between sips, we took bites of salty cheese and warm bread fresh from a stone kiln. Though most of us had just met the day before, we were feeling quite jovial in the afternoon sun. George Ramishvili and Yerkin Tatishev stopped by. The festival’s two founders, who’d grown to be like brothers, had met a dozen years before—around the time that Yerkin had lost his brother Yerzhan.

‘My brother died,’ Yerkin confided. ‘Actually, he was murdered.’

Taken aback, we expressed our condolences. Yerkin gave us the basic details of a story that had made local headlines. Yerzhan had been the chairman of Kazakhstan’s BTA bank in its glory days, when its western partners had included Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse. In 2004, on a hunting trip, a businessman named Muratkhan Tokmadi had shot Yerzhan in what was initially ruled an accident. Within months, Yerzhan’s ambitious partner, Mukhtar Ablyazov, became BTA’s chairman. Ablyazov brought Yerzhan’s heir, Yerkin, into the bank’s management. But Yerkin grew suspicious of Ablyazov. He hired American forensic experts to look at the shooting. They concluded it was deliberate. After Ablyazov’s embezzlement scheme came to light in 2009, Tokmadi testified in a new proceeding that Ablyazov had recruited him to kill Yerzhan because Yerzhan wouldn’t cooperate with Ablyazov. Tokmadi was later sentenced to ten-and-a-half years in prison.

As he sipped wine with us, Yerkin said, ‘I promised my mother that no blood would be spilled. I’ve kept my word. All the people who took part in the conspiracy have been convicted. Except one. And we will get him.’

Still a fugitive, Ablyazov has since been convicted in absentia as an accessory to the murder. He maintains his innocence, insisting that all litigation against him is politically motivated. Believe him or not, the killing made me wonder about Yerkin’s supposed involvement in Ablyazov’s embezzlement scheme. Why would Yerkin help a man he suspected of murdering his brother?

The next day, after a soaring evening performance by the Georgian Philharmonic, George Ramishvili was nice enough to chopper us back to Tiblisi. He also hosted a lunch on the patio of Andropov’s Ears and arranged a tour of the National Gallery even though the museum was closed. His largesse was remarkable, but he insisted it was nothing unusual for Georgia. ‘A poor man,’ he said, ‘will sell his last furniture to offer a proper feast to a stranger.’ (Presumably, everyone would have to eat on the floor.)

Further illustration of Georgian generosity came from Dato Magradze. Born in 1962, Dato is a Nobel-nominated poet. He also served as Georgia’s minister of culture and a member of parliament before breaking ranks with Shevardnadze’s government and joining the Rose Revolution. Along the way, he wrote the words for the Georgian National Anthem. My friend Tom, who helped publish the first English collection of Dato’s work, introduced me to him at Tsinandali. Tall, with vigilant eyes, a sly smile, and a spacious personality, Dato promptly issued an ultimatum.

‘Before you leave,’ he told us, ‘I must show you my Tbilisi!’

So, on our last night, we met up with him in the historic Sololaki neighbourhood, where venerable Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian houses of worship coexist with hip cafés and boutiques. Dato escorted us down its streets. Winking and tipping his hat to passers-by, he seemed to know everybody in Tbilisi.

We pulled into Vino Underground, a subterranean wine bar co-owned by local vintners. We sampled a few glasses of Tavkveri, a dry red, as we waded into politics. I’d asked Dato earlier whether he supported anyone in that week’s presidential elections.

‘I prefer to be independent,’ he said. ‘But, when I see the view from my window, I have to get involved. I do state my opinion. I challenge people to vote with their conscience.’

He’d made it known that he favoured former foreign minister Salome Zurabishvili, rather than Grigol Vashadze, the candidate backed by former president Saakashvili.

‘I don’t believe in bringing back the Sakashvili style of government,’ Dato went on. ‘I feel the Georgian spirit needs to be revived.’

We popped into a pub for a quick chacha. Then, looking at his watch, Dato said, ‘Oh, we have to get to dinner!’

He led us up a steep lane. Far atop Sololaki hill, the Mother of Georgia statue, bathed in light, seemed to hang like a lantern. Dato’s home was trimmed in gingerbread-moulding and filled with paintings and sculpture made by his friends. In the dining room, Dato’s wife, Lali Andronikashvili, had set the table with one of the patterned blue cloths officially designated as part of Georgia’s ‘intangible cultural heritage’. Dato uncorked a bottle of white. We dug into plates of assorted cheeses, fresh herbs, tomatoes, radishes, breads, and chicken in walnut sauce. Just when I was ready to burst, Lali blindsided us with ‘the main course’—a groaning platter of roasted meats and vegetables. Honestly, if this woman ran a police interrogation room, every suspect would talk!

Dato pulled out a guitar and sang several aching ballads. You didn’t need to know Georgian to feel him conjure what, in flamenco, they call duende. The doorbell rang. It was George Ramishvili and Giorgi Rtskhiladze, both old friends of Dato. Having come from a government meeting, they loosened their collars and filled their glasses.

I attempted a toast—expressing my admiration for a country where music-loving plutocrats can easily break bread with a revolutionary poet.

‘Hey,’ cracked Giorgi, ‘Trump had Kanye to the White House!’

I can’t say exactly what happened between these guys and Trump. Giorgi was friendly enough with Trump’s fixer Michael Cohen to joke in 2016 about rumours of compromising tapes. According to the report by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, Giorgi texted Cohen: ‘Stopped flow of tapes from Russia but not sure if there’s anything else.’ Giorgi later told investigators it was playful banter and that he’d subsequently heard the tapes were fake.

George Ramishvili maintains Silk Road got unfairly sucked into the ‘unprecedented media focus on the Trump organization’s business dealings.’ I will say that The New Yorker story neglected to mention that Big Four accountant KPMG audited the BTA loans to Silk Road and found no malfeasance. The article also did not mention that the Georgian prosecutor’s office investigated money-laundering charges against Silk Road for over a year and found no wrongdoing. And, again, why would Yerkin help a man he blamed for his brother’s death?

As to why Silk Road forked over US$50 million to the Kazakh government, Giorgi contends it was to avoid litigation and ‘to maintain a relationship’ with Kazakhstan, where Silk Road still has interests.

It’s hard to say what goes on in any privately held company, much less one with enough nesting-doll subsidiaries to earn 1,901 references in the Panama Papers.

I do believe George and Yerkin’s patronage of classical music is a good thing. (See earlier sidebar for details on the 2019 Tsinandali Festival.) I can corroborate that, if you come to Georgia, you will be hugged and air-kissed and fed till your stomach is declared excess baggage. I will particularly savour one of Dato’s dinner salutations. He recalled how, in James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, toast-making Gabriel Conroy declares that Ireland’s tradition of hospitality ‘is unique … among the modern nations.’

Raising his glass, Dato proposed, ‘May each nation believe it is the most hospitable in the world—and may each be right!’ •

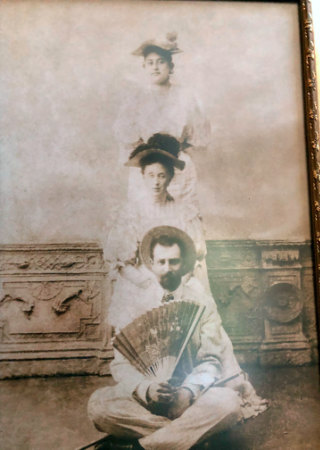

Top and above left: Photos of Prince Alexander and family. Above right: Icon of St. George.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Making excuses on the road in Madagascar

George Rush has had a long-time fascination for Madagascar, finally venturing there to discover the nature and culture of the isolated island nation

Photographed by the author

Errands for the soul

Stanley Moss heads back to Varanasi, then to Amritsar and Dharamshala, where they were granted an audience with HH the Dalai Lama

Photographed by the author; audience photographs by the office of HHDL

Delirious Dubrovnik

Stanley Moss finds a gem on the peninsula near Dubrovnik, a discreet, deluxe hotel with first-class food in a personal, authentic setting

Photographed by Paula Sweet

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.