Stephen A’Court

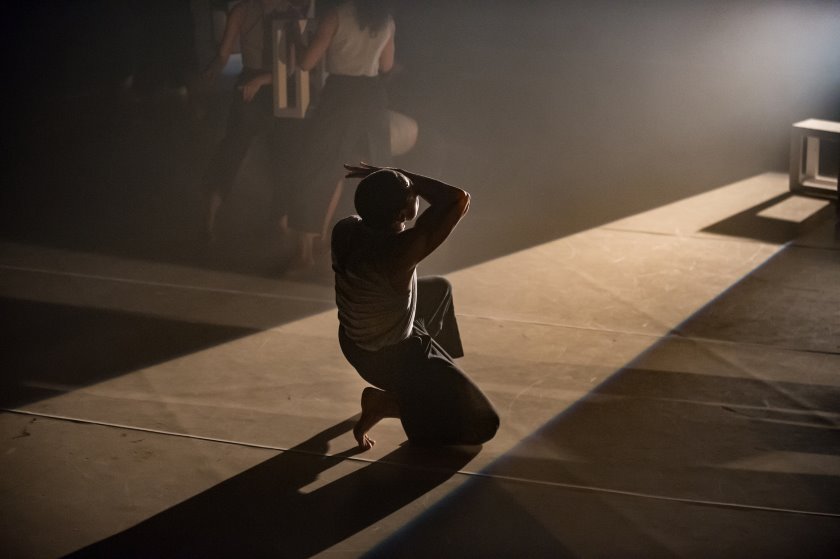

Top New Zealand School of Dance third-year contemporary students. Above Latisha Sparks, William Keohavong and Jadyn Burt.

The New Zealand School of Dance always puts on a stellar performance, especially with its final-year class, but Karst, its Choreographic Season for 2015, adds some unexpected and welcome twists, and puts audience members into the performance, at least during the first half.

Arriving at Te Whaea, you’re aware something is different: instead of the waiting area that you’re accustomed to, there’s blackness. The auditorium, meanwhile, has become the new waiting area, with TV screens showing the final-year students’ faces in the centre, and the tables moved within. As the show started, we were escorted to the catwalk above the plaza, where the show takes place.

Wind over Sand (See below) gives you a different perspective as we viewed this from above, or on the stairwell, and there was some getting used to seeing a performance while standing. However, this didn’t detract from the enjoyment at all, and, as it turned out, Wind over Sand was simply a prelude to the cleverer and more entertaining numbers that were to follow. Audience members in wheelchairs were wheeled to ground level and watched from there, but would have had the same appreciation we did.

Felix Sampson, one of the class of ’15, motioned us comically to come down from the stairs, surrounding the stage, where Jadyn Burt danced to Exhibit: J, using a single box as her prop, positioning herself on each side as she explored it.

Seated at what would be our vantage points for the rest of the evening, Samuel Hall and Jag Popham began their number stood at different corners of the set, one motioning ever frantically while the other stood still. Without Regard contrasted movements and styles as the pair moved closer on stage.

Another seamless segue, as bright lights shone from the end of the building, and we were into Volume, set to Planningtorock’s ‘Public Love’, with the notes asking, ‘If you could live in that place every day? Think of the possibilities.’ But, like some of the performances in Karst, those possibilities had a catch, the choreography signalling the old adage of, ‘Be careful what you wish for.’ (Manifest) the Subliminal, similarly, strikes at the idea of balance, with backgrounds moving, essentially reiterating that the universe is structured the way it is for a reason. Upset that balance, and there is chaos. Loscil’s ‘Esturine’, with its repetitive rhythms and crackles contributed to an airy, almost lonely effect.

Fragile Mortalities was the first number that blended visual effects as each dancer brought out a television screen with their face on it, looking cheerful, yet each began revealing their insecurities more and more, performing their internal collapses. In a similar world of paranoia, You Are My, set to the Harry Roy arrangement of ‘You Are My Sunshine’ saw cheer erupt each time the music started, but the despair soon strikes one dancer, then more and more, in different forms; words displayed at the back of the set disintegrated from hopeful to hopeless. At this point, one wondered if this reflected concerns students had about their lives in 2015; after all, who are better insights into the Zeitgeist, and more focused on the future than those who have settled in their careers?

The 79 Bonnie Special brought the mood up slightly with the background video showing what appeared to be an old cassette-recorded programme. A tribute to New Zealand singer Connan Mockasin, using his song ‘Do I Make You Feel Shy?’, this was a comedic take, with Georgia Rudd donning a silk gown and shades, and lip-synching into a microphone, perhaps telling a tale of fleeting fame and the low-rent world that some inhabit, thinking they are on the A-list. Again, it seemed to be on the pulse of where popular culture is, in what might be deemed a post-reality-show world. Such shows still air, but in terms of the cycle, are they beyond maturity?

Unfortunate Help, with Jessica Newman and Latisha Sparks in the main roles, see the dancers together with lengthy cardboard tubes, but pulled apart, others’ attempts at rejoining failing to unite the pair, who also fall into their darkness. At its end, Rowan Rossi emerges on stage, curious about the state of affairs, and we hear Sampson utter complete sentences for the first time, beckoning others to go as he and Rossi begin Only in Istanbul. Sampson narrates the piece, joking about Rossi and providing personal details about him, and the two come to dance in unison. Only in Istanbul is described as ‘A rigmarole’ in the programme notes, and the description fits: the movements are expert, but the story culminates in ‘Istanbul, Not Constantinople’ and the entire cast reemerges for Absent Ritual, a number that leaves Karst on an upbeat, positive note.

Te Aihe Butler’s music, which is at the fore in Absent Ritual, actually comes through in many of the numbers, and is the effective, unseen uniting force behind Karst. It deserves special mention.

Taken together, one does have to ask: where are society and culture today? Are we in times where we are leaving some of our citizens behind? What is the value of fame if it lacks fulfilment? If the students, who choreographed the works, are forcing us to ask these questions, then they have succeeded.

The season is directed by Victoria Colombus, an NZSD graduate, and is the most innovative Lucire has reviewed at the venue. Colombus rightly used the space to great effect, and we hope that there will be future performances there. Removed from the traditional shape of the auditorium, the students made very effective use of their new stage, and the architectural structure helped give a scale beyond what the auditorium offers.

Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School students worked on the lighting, which also showed a youthful passion combined with professionalism, while Donna Jefferis’s costumes were the icing on the cake.

The season runs at Te Whaea in Newtown, Wellington, till May 23, with tickets from NZ$12 to NZ$23. Bookings are available at www.nzschoolofdance.ac.nz.—Jack Yan, Publisher