|

fashion: feature

All in the jeans All in the jeans

Sylvia

Giles examines the history of denim jeans in the context of popular

culture

Expanded from

issue 23 of Lucire

POPULAR CULTURE has a lot to answer

for. Of all the cultural carnage created for the sake of being popular

with the masses, fashion could be considered the worst offender.

Defined as the ‘culture of the people,’ it relies on mass communication,

mass media, mass recognition but most importantly, mass acceptance

of symbols and icons that are presented to us. It often involves

the use of icons that become so everyday their original meanings

are lost. While this certainly could be said of denim, the longevity

of its popularity has meant it has transcended all fads and fashions,

making it a fluid gauge of popular culture that has morphed and

reinvented to suit the requirements of an erratic society.

While everyone is all too familiar with the Levi

Strauss story, the influence of pop culture over denim includes

rock stars, artists, intellectuals and film stars, and began with

the emergence of the USA as a superpower

after World War II. This supremacy would slowly translate to dominance

of popular culture across the globe. Denim was quintessentially

American, typically branded and fundamentally mainstream. In its

early history, denim embodied the wholesome all-American hero, the

cowboy and the labourer. It was seen as having been bastardized

by biker gangs around the 1940s, and it was the first sight of what

would be a long-standing relationship between denim and the rebel.

Denim companies had a token attempt to portray themselves as a socially

responsible choice of apparel. In 1953, Lee ran its first advertisement

to teenage youth that promoted denim as an appropriate choice for

school, in response to the banning of denim in schools. But ultimately,

denim was to cash in on a rebellious youth and an American cultural

explosion.

It wasn’t until Marlon Brando endorsed jeans

with the kind of placement companies dream of in 1947. In A Streetcar

Named Desire on Broadway, and the resulting movie, jeans emerged

into the realm of pop culture. James Dean, Paul Newman and Marilyn

Monroe all reciprocated and jeans reached their cult status, with

associations of stardom and celebrity. Pop icons were also used

to export to other markets, such as ventures into France with Brigitte

Bardot, and her Italian equivalent Gina Lollobrigida.

It also became an icon of intellectuals, particularly

in New York, as early as the 1940s. In 1949 Jackson Pollock was

photographed for the cover of Life fittingly in paint splattered

denim, and began something of a craze within the world of abstract

expressions. The style was echoed by Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein

and Saul Bellow. Warhol, in particular, was fastidious about his

jeans. He also went on to became the cover star for l’Uomo Vogue’s

special denim issue in 1980. He once said, ‘I wish I could invent

something like “blue jeans”. Something to be remembered for. Something

mass.’

During the 1970s, western pop culture’s influence

was being felt across the rest of the world. Within my parents’

library is a beautiful Russian book that my mother acquired while

on a train travelling through Russia. The currency for this book

was, in fact, her pair of Levi’s, spotted by a local passenger desperately

wanting them for ‘his girlfriend’. The trade took place. She still

treasures the book, and effortlessly bought a replacement pair on

her arrival back in the UK. The reality

is that in Russia in the 1970s, a pair of Levi’s could have reached

a much higher price than a paperback. Jeans had become a symbol

of western decadence because of the difficulty involved in getting

a pair in non-western countries. But that the demand existed at

all was an indication that the influence of western pop culture

was now sweeping across the entire globe.

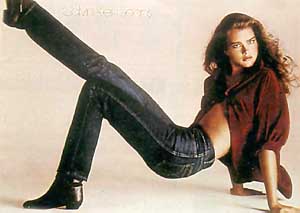

Fashion took on a life of its own in the 1980s,

and the creation of pop culture-turned-monster. The cult of the

supermodel and celebrity reigned. In 1980, Calvin Klein used a 15-year-old

Brooke Shields to communicate the sexuality of jeans. The use of

the boldly stated line, ‘Between me and my Calvin’s there is absolutely

nothing … if they could talk I would be ruined,’ was married

with a provocative, leg-spread pose. The ad was pulled from many

television stations. Klein’s rebuttal was left at a ‘Jeans are sex.’

He hardly needed to say more. Conservative Middle America could

not tame the beast that had become pop culture, and Klein’s sales

leapt to $180 million a year. Likewise, fashion houses such as Versace

and Dior launched high-end denim wear lines, modelled only by supermodels

in sexual, powerful poses.

Music’s contribution to fashion is generally

a treasured one. As a true voice of the street, it is unlike the

devised marketing strategies in the name of consumerism. Music is

also, in general, more politically charged than the impression left

on pop culture by movie stars. Elvis, for example, refused to wear

jeans on stage, after having been schooled by black musicians in

Memphis, where denim rang of cotton fields and share cropping.

In 1975, in a small bar in New York called CBGB,

Television bassist Richard Hell graced the stage in a ripped T-shirt

and jeans. It was observed by a very impressed Malcolm McLaren,

who recreated the look with the Sex Pistols, with the help of Vivienne

Westwood. This was the beginning of the punk movement, which was

to take on a life of its own. Denim sat alongside leather, vinyl

and safety pins. While the untrained eye was to brand it an “uglification”,

punk communicated a deep dissatisfaction of a generation that felt

deeply let down by the world.

The Ramones, also Television fans, created a

variation of their own, teaming their jeans with black leather jackets

and white T-shirts. Their manager, Danny Fields, was also a figure

in the Andy Warhol Factory scene. He easily identified why their

look resonated with youths: ‘It’s an easy enduring look and costume

that any kid in the world can create. It’s the way you face the

street.’

If the pop culture influences on denim history

read like a Who’s Who of the 20th century, the 21st century

would signify a break-down of the concept of “the mainstream”, and

the emergence of subcultures and individualization. The internet

is now the ruling authority on pop culture. Information is traded

in an instant. It has reduced the cycles of fashion and fads, which

now happen instantaneously and the globe. But by far the most interesting

outcome has been the explosion of subcultures—a fragmentation of

the mainstream. If you put denim distressing into Google

you will find many a website and thread devoted to home ‘distresseurs’.

The most interesting include one fashion devotee that had buried

his jeans in his back yard for an entire year. After a wash they

came up better than jeans one might find in the scientific laboratories

of any well-known, excessively funded denim factory. Likewise, with

the recent tendency towards very blue denim with very little interference,

anecdotal evidence filters through the web of fashion victims refusing

to wash their jeans in an effort to keep them as authentic to the

original denim as possible. But giving a voice to the public that

sits on the same forum as fashion reviews from Paris, New York,

London, suddenly equates the consumer with the label, giving a new

voice and authority to fashion at the ground roots.

continued

Add

to Del.icio.us | Digg

it | Add

to Facebook

|

Main photograph: Brooke Shields in her Calvin Klein print ad.

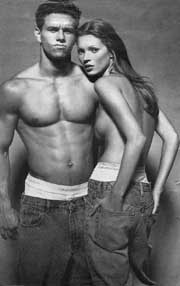

From top: Kate Moss appears in another sexy Calvin Klein

jeans advertisement, pushing more boundaries. Jeans from Free Religion.

Doosh Roadrunner jeans in Smoke. Levi’s Super Fit.

Within my parents’ library is a beautiful Russian book that my

mother acquired while on a train travelling through Russia. The

currency for this book was, in fact, her pair of Levi’s, spotted

by a local passenger desperately wanting them for ‘his girlfriend’.

The trade took place

|