Above: Tony Curtis and Roger Moore in the première episode of The Persuaders (1971), showing turn-of-the-decade men’s fashion.

FASHION Twenty twenty is not the first time that the turn of a decade had so much change. Jack Yan looks at previous new decades, and remains optimistic

Abridged from the July 2020 issue of Lucire KSA

Elisa Rolle/Creative Commons 4·0

Elisa Rolle/Creative Commons 4·0

Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures

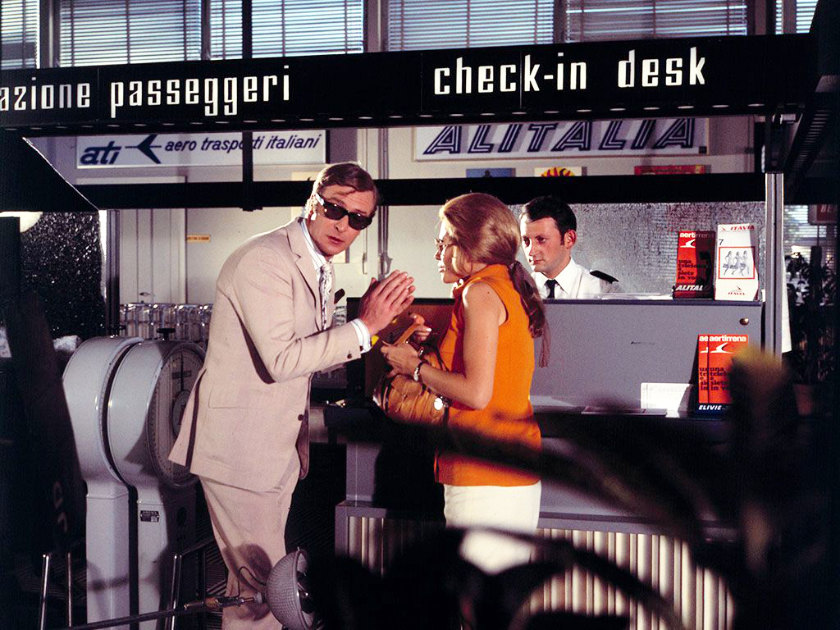

Top: As one decade ends and the next begins: Ossie Clark Lamborghini trouser suit, 1969, and Bellville Sassoon coat, hand-painted by Richard Cawley, 1970–1. Above: Michael Caine in a stylish suit in The Italian Job (1969); actress Maggie Blye appears with Caine.

Jack Yan is founder and publisher of Lucire.

There is perhaps little coincidence that a recent project, begun by HRH Prince Charles in the UK, was called ‘the Great Reset’, involving the World Economic Forum and the Prince’s Sustainable Markets’ Initiative. There’s been a sense of a “reset” throughout the world, not just with COVID-19, but with events ranging from the Australian bush fires that began 2020 to the Black Lives Matter marches in the wake of the killing of American man George Floyd. Go back to 2019 itself and the student demonstrations led by Greta Thunberg were another sign that there is a desire for change, while the protests in Hong Kong signalled that some legislation in the Chinese city had pushed part of the population too far.

A brief glimpse back through history suggests that it is easy for us to use new decades as markers for changes. The one prior to 2020 that was perhaps the greatest marker in most readers’ lifetimes was the new millennium in 2000, a year that felt “futuristic” to those who lived in the 20th century. Wind the clock back, and Americans might say that 1980 was a watershed year, with the election of Ronald Reagan to their presidency, and the promise he brought after a troublesome decade that saw Watergate and two energy crises. Head back another 10 years, to 1970, and there was a sea change in fashion, spurred on by what were then recent events: the US Civil Rights’ Movement, the counterculture, and a dissatisfaction with their country’s involvement in Vietnam.

This is not to minimize the changes that had been taking place prior, but it would not be wrong to say that there are people who see new decades as fresh starts, and that this is far from being a new phenomenon.

Being a child of the 1970s, I was always fascinated by the decade change that happened just prior to my birth. If you watch film and television shows from the time, there appeared to be a real desire to mark the novelty of the new decade. Traditional men’s hairstyles gave way to big sideburns. Women’s hair also gained volume. Fashion went floral with yellows, mustards, oranges and browns surfacing en masse. The cuts might have been still a little 1960s, but the colours were signalling a departure. One of the last films of the outgoing decade, The Italian Job, was big on colour for men’s suits: purple was all right as a way to push traditional blacks and navies out.

continued below

Paramount; ITC/Carlton Communications

Paramount; ITC/Carlton Communications

Above, from top: Mission: Impossible’s cast photos, beginning with season 2; by season 5 in 1969 restraint was out and sideburns were in. Roger Moore and Tony Curtis in the première episode of The Persuaders.

The Brady Bunch and Mission: Impossible, two US TV shows that spanned the 1960s and 1970s, showed not just an evolving style, but sudden changes between seasons as the 1970s dawned. The same phenomenon could be observed with That Girl: evolutionary for most years between 1966 and 1969, then hairstyles and wardobes suddenly changed for 1970; even the theme tune changed. Co-star Ted Bessel’s ’do was noticeably different that year.

Get into 1970 and 1971, The Persuaders, the British TV show, sees frilly shirts for men as part of formal wear, and womenswear was more rustic. The clean-cut styles were suddenly history. Sideburns were still big and lapels and flares were growing.

An indication of where people saw the future can best be found in another British series, UFO, made in 1970 but set in 1980 (and possibly later, based on some scripts). The makers of the series expected things to evolve gradually: there would still be miniskirts and the cars would get bigger, trends that they would have observed as the new decade dawned. They also foresaw wigs being a fashion staple. No one suspected that efficient cars would become desirable or that the flouncy, English countryside fashion of Laura Ashley would be in vogue.

It is a common mistake to think that things will develop on the same path they always did, and granted, hindsight makes us all wiser, but the observation of such trends should inform us—and maybe help us navigate the future. They might help us make sense of the times we now face.

To me, those muddy colours and impractical designs of the early 1970s portend less rosy economic times ahead, as they feel like fashion has lost its way, reflecting the greater mood, or the Zeitgeist.

Big lapels, big sideburns and big hair aren’t practical but they seem to indicate fashion trying hard to stay relevant and eke out some extra sales, reinventing something that has already been invented. When changes are merely cosmetic, when new products have no noticeable advantage over the ones they have replaced, then to me it signals that certain sectors have become bereft of ideas and disruption is coming.

Bringing things forward to the decade just passed, there were some signs. Apps and e-commerce tied to them didn’t promise new fashion or consumption patterns, for instance: they simply sped up the old system. Fashion and luxury, Lucire travel editor Stanley Moss points out in his latest Global Brand Letter, are significant polluters, ‘responsible for more of the world’s CO₂ emissions than the international aviation and shipping industries combined.’ He adds, ‘Synthetic fibres are being found in the deep sea and only 13% of total material in the clothing industry is recycled … Brands that preferred to over-manufacture by 30–40% have been making far too much product for far too long. Much ends up incinerated or in landfills.’

Fashion is not alone, with products that we often don’t need winding up in online shops. In the automotive sector, I’ve observed vehicles such as the Mitsubishi Mirage replace a far more efficient and better designed Colt from the decade before, and the rise and rise of SUVs could not be positive on so many counts: these are often inefficient designs that are overpriced and, given the inertia they generate along with a higher centre of gravity, not necessarily safe. It is no coincidence that this magazine has often named smaller, more fuel-efficient cars the ones ‘to be seen in’ each year, as our contribution to waking people up from their consumerist slumber. Our most recent one was the Alpine A110, a compact and light French sports car that is the antithesis of the SUV.

As we will see in this issue of Lucire, the traditional runway show is being seen as an extravagance, and with most major European labels cancelling their cruise (or resort) 2020–21 shows, Chanel excepting, there could be a greater move to online shows, to at least demonstrate that change is in the air. Shanghai Fashion Week was the first to provide a fully digital showcase, thanks to China having an advanced e-commerce and digital platform, with the likes of Alibaba and Tmall. Some are going even further to predict the end of bricks and mortar, though we’ll hold back from that at Lucire: there will always be a place for consumers to try on their wares before purchase, if only the high street would stock better fashion and fewer fast items. That, too, is an area ripe for change, where quality must take place over quantity again. We have also seen many labels profiled in this magazine that have abandoned the idea of seasons: this isn’t a phenomenon that came with COVID-19, but it is one that could well become the norm as labels adjust to the new reality.

You could make a very strong argument for saying that many of these trends have created, or at least are connected, to the major crises of 2020. Bush fires and climate change are linked, the latter driven by increasing industrialization to cope with consumption and urbanization. Wuhan became the source of an outbreak because of a mixture of poor sanitary conditions that are the result of increasing inequality and urbanization, with many multinationals setting up shop there without regard to the environment and natural habitats that have been disrupted.

The secrecy observed in China and the violence perpetrated against black Americans in the US are nothing new, but these have come to a head lately because people have reached a point where both are no longer tolerable by a large enough group of people.

So, we have to ask ourselves: what lies ahead?

We might take a lesson from the past once more.

Come 1980 and there seemed to be a collective sigh of relief in the west as the 1970s were cast off: disco became passé, and neons and electronica conveyed modernity in readiness of more optimistic times, in the belief that perhaps people had been through enough in a decade marked by uncertainty.

I’m not saying COVID-19 or the Black Lives Matter protests will take another decade to resolve themselves. Far from it. But I am saying that ignoring the roots of these problems by a hastened return to the old normal will not fix these issues. Humanity is faced with the opportunity to reinvent itself anew, and it needs to decide just what had been so wasteful in the decade just gone. New jobs will be created as a result of this: the cessation of traditional catwalk shows, for instance, will spur a demand in specialists who can produce them online.

We may, therefore, recognize the folly of overproduction; the expense of running an SUV; the goods that we never needed; the sheer wastefulness of human energy if one part of a country’s population lives in fear because of the colour of their skin. We may have noticed the enjoyment we have from cleaner air and quieter neighbourhoods.

Just as the western citizen of 1960 would not recognize 1970, ideally this could be a decade of such positive change that we will not recognize 2030. But I argue that the same western citizen of 2010 could recognize 2020 because of the lack of progress, and maybe even some regression, in the last 10 years. President Donald Trump’s election could be foreseen by anyone who noticed the earlier conservative movements marked by Sarah Palin’s ascension on to the American political stage in 2008.

Fashion, then, will have to shift to become more practical, and be of better quality. It may have to appear more professional as people seek jobs and head to work. The industry will change, and hopefully those countries and territories that have found themselves in a post-COVID society will take a positive route and demonstrate the first signs of optimism, just as we observed of 1980. Sometimes the more uncertain, the more positively things turn out. By 2022 we may see the first fruits of this better world, if we collectively do the right thing and rethink the way we treat our world and others.

As George Taylor proffered his hemline theory in 1926—the anecdotal idea that skirt lengths and economic prosperity are connected (with the economy driving the length, incidentally, not the other way round)—observers of fashion will look back at this era and write about the massive shift, just as I pondered about 1970. •

Mabalu/Creative Commons 4·0

Mabalu/Creative Commons 4·0

Top: Laura Ashley dresses from the 1970s, which few in 1969 could have predicted. Above: The light, sporty Alpine A110, the antithesis of the SUV.

Top: Laura Ashley dresses from the 1970s, which few in 1969 could have predicted. Above: The light, sporty Alpine A110, the antithesis of the SUV.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Print’s the next big thing

With a web-savvy generation who know about Big Tech’s issues with privacy and surveillance, print magazines are looking like a great time-out from digital screens at every moment of the day. Jack Yan looks at the trends

Where have the fun fashion magazine websites gone?

Removing the design and content review scores from Lucire’s link section is the result of much larger forces in publishing and technology, as Jack Yan explains

Unmasking the history

From the history books to hot off the runway: Victoria Whisker looks at how the face mask has evolved from necessity to a fashion accessory and why so many people are creating their own

First published in the July 2020 issue of Lucire KSA

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.