FASHION There’s been a lot of talk in marketing circles about the next influential demographic, Generation Z. Jack Yan looks at how fashion brands can appeal to them

Main photograph by Livvy Adjea/Unsplash

From the October 2021 issue of Lucire KSA

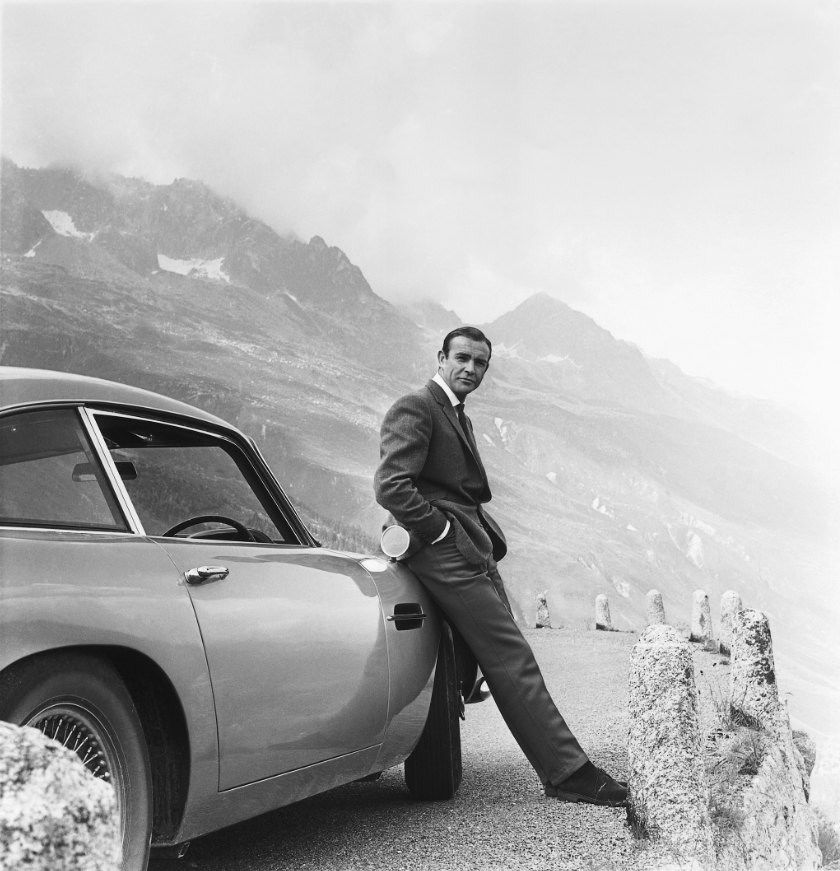

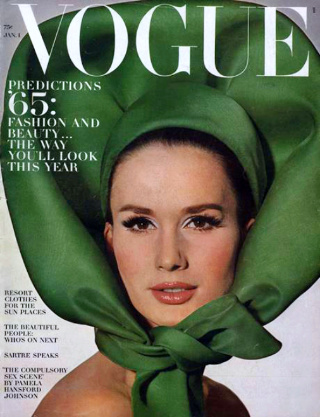

Danjaq LLC/United Artists; Chantal Lim/Unsplash

Header photo: Mary Quant’s designs displayed at the V&A. Top: One enduring sign of Britain’s energetic advance in the 1960s, the cinematic James Bond. Here, Sean Connery is at the Furka Pass in Switzerland during the making of Goldfinger. Above: A young woman in Lijiang, Yunnan, China. Below left: Vogue, January 1, 1965, when Diana Vreeland coined the term youthquake.

The 1960s have been a decade of some myth-making in the west, as it is easy to pinpoint the rise of a number of trends that coincided with this period. We discussed in an earlier Lucire how the start of the decade appears to bring with it some novelty, even though the threads leading up to those changes had been sewn into history years before. It might be argued, for instance, that the period between 1963 and 1973 marked just as tumultous a change as between 1960 and 1970, but we are drawn to tidy, round numbers.

Among those changes in the 1960s was marked by the word youthquake, first recorded in usage in Vogue in 1965. It was the idea that cultural change was spurred by young people, and in Vogue’s usage it specifically referred to the uprising of youth culture in London. Vogue editor Diana Vreeland is credited with coining the word, and there is certainly some truth behind London becoming a cultural centre at that point. Youth did seem to drive arts and culture: production designer, Ken Adam (later knighted) equated it to a burst of energy, where Britain felt conservative through the 1950s, before an eruption occurred in the next decade.

Among those changes in the 1960s was marked by the word youthquake, first recorded in usage in Vogue in 1965. It was the idea that cultural change was spurred by young people, and in Vogue’s usage it specifically referred to the uprising of youth culture in London. Vogue editor Diana Vreeland is credited with coining the word, and there is certainly some truth behind London becoming a cultural centre at that point. Youth did seem to drive arts and culture: production designer, Ken Adam (later knighted) equated it to a burst of energy, where Britain felt conservative through the 1950s, before an eruption occurred in the next decade.

There were labels such as Mary Quant making headlines with higher hemlines and Twiggy coming into prominence; in music, the Beatles rocked on to the charts around the world; and in film, the James Bond series kicked off with colourful and exotic locations that had seldom been seen in cinema before. The end of conscription in 1960 meant there were more teenagers participating in society (the last conscript finished his national service in 1963), coming off a decade of relative prosperity in both the US and the UK. They had earned more because of this prosperity, driving economic change; by 1959, four million out of five million UK teenagers were employed, and were able to keep the majority of their earnings. Technological developments included early colour television sets and transistor radios. It was not all positive: there were reports of drug abuse, and crises in housing.

Fast forward one generation and there isn’t quite the same romance with the 1980s and 1990s. The 1980s were regarded as a decade of consumerism, partly spurred by technology (the Walkman, the video cassette recorder, the home computer) and economic changes in the occident. However, it has also been written that youth of this generation (Generation X) were more media-savvy, having grown up their entire lives with television commercials. The educational series Sesame Street was concocted to deliver numeracy and literacy skills to young Americans in video- and soundbite fashion, because attention spans were shorter, and commercials had become pervasive. The result from this lifetime exposure meant, according to at least one commentator, that youth from this period had built-in lie detectors, if a company made claims that were instinctively untrue in mass media advertising.

Media attention these days has turned toward Generation Z, the group of ‘zoomers’ that succeeds millennials, and might be defined as those born between 1997 and 2012. As with any other demographic, there is no agreement on the years precisely. But this group can claim to have been exposed to online media since youth, if not birth, and if the Xers were savvy about traditional media and its advertising, then Zers had the same cunning with online messaging.

Whether that is true or not remains to be seen as more of Generation Z emerges in society. It is also too early to tell what cultural movements they will drive. But there are some interesting representatives of this generation: Greta Thunberg, the activist, is able to point to the hypocrisy of the generation before in the west as it failed to deal with the climate crisis, and mobilize mass protests globally with her and her supporters’ use of internet tools. One wonders, however, if solutions will be forthcoming from the next generation once idealism is replaced by practicalities, and they witness the inertia that certain institutions have. We can only hope they can create a better world for themselves. Protesting about the environment is a good start, and suggests at least an awareness of the planet’s health.

On social media, young people are indeed less likely to get fooled by “fake news” or scams, and as social media sites have been mainstream since the mid-2000s, there are relatively few Zers who remember a time before them. They are also more opinionated as a result, since the sites encourage expressing what they think and feel, and with the rise of certain technologies—broadband, more powerful computers, mobile devices, better cellphone cameras—they have been able to do so easily.

Recent research by Vogue Business suggests that the exposure Generation Z has had to all existing forms of media have given them a sophistication that older generations possess. Focusing on the mainland Chinese market, the trade publication identified four types of Generation Z, which may well be mirrored in other countries. After all, Generation X was said to have been one of the first global generations—if you were lucky enough to be in a society where there was television—because of converging tastes in music, thanks to MTV. It’s likely that with technological convergence—and this is far wider than what television achieved at its peak—there is more commonality between representatives of Generation Z around the world.

China, too, is instructive as a consumerist nation, where luxury is well understood, according to the publication. Interestingly, it is the male Gen Z shopper who spends 20 per cent more than females in fashion and luxury.

The four categories the publication identified begin with the ‘understated classicists’, who seek understatement and fashion-forward design; the ‘avant-garde showmasters’, who want edgy, bold designs, including genderless looks; the ‘fashion experimenters’, who are trend-driven and trying to figure out their personal style; and the ‘artistic expressionists’, who look for lesser-known designers because they want to be unique and different.

These tell us that Generation Z doesn’t differ from previous generations in terms of the types that exist: each of these was arguably reflected in earlier generations.

What is more fascinating is what draws them all together. There’s some celebrity fatigue among this group—while some do have influence (see Lucire issue 42, where Kim Kardashian guested with influencer and livestream host Huang Wei, a.k.a. Viya)—they call for more sophisticated and creative campaigns. There is an expectation that in some cases, consumers drive manufacturing (also outlined last year in Lucire), with plants making goods based on consumer orders.

Consumers also feel they have a part to play in influencing and nurturing brands themselves, a development of what we saw in the previous generation. Perhaps this group has grown used to the collaborations between fashion and other brands, some of them with unlikely bedfellows. Last generation, with the rise of social media, we saw organizations lose the ability to both communicate and control their brands’ image, and subvertising (the parodying of brands, often to subvert their message) entered the vocabulary. It became just as important to manage audience reactions to brands as it was to create corporate identity manuals or steering creative direction of a brand. The next logical development is for brands to take on consumer thoughts about where they should head.

With China having developed its own luxury brands, there’s no allegiance to following foreign ones. There’s an additional development to this: with the proliferation of information, Generation Z is prepared to do more research to seek out something different. They also pay attention to the brands’ heritage and culture. In other words, those back stories are important—ones that organizations might once have told their teams internally to build up corporate culture are now as relevant to consumers themselves. They understand that this is a global society, so why not look at what the world has to offer?

These last two phenomena—the consumer nurture of brands and a desire to understand their heritage and culture—show a unification of how brands are communicated: that there is a decreasing need for brands to separate internal and external audiences. In many ways, the stories in Lucire have reflected that, providing more depth and trying to understand the internal cultures behind the labels. It’s certainly not restricted to China.

Overall, these are positive developments. This level of transparency had been forecast by this magazine in the first part of the 2000s. These are progressive trends, driven by a global generation that wants to be treated intelligently. •

Jack Yan is founder and publisher of Lucire.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

New decade, new energy

Twenty twenty is not the first time that the turn of a decade had so much change. Jack Yan looks at previous new decades, and remains optimistic

Abridged from the July 2020 issue of Lucire KSA

Print’s the next big thing

With a web-savvy generation who know about Big Tech’s issues with privacy and surveillance, print magazines are looking like a great time-out from digital screens at every moment of the day. Jack Yan looks at the trends

Fast and furious fashion

After decades of being the realm of early adopting computer users, e-commerce is now the norm—but will a western or Chinese model prevail? Bhavana Bhim asks

First published in the September 2019 issue of Lucire KSA