Volante

There may have not been a coherent thread at the Biennale di Venezia this year, entitled Foreigners Everywhere, but Stanley Moss did manage to find true treasures among the repetition and pretentiousness

Photographed by Gioia Meller Marcovicz

With so many diverse points of view on this year’s Venice Biennale—entitled Foreigners Everywhere—it’s difficult to label oneself a contrarian. This year, everyone is. A casual sampling of published reviews makes us wonder: did all these well informed people see the same exhibition? The Biennale sprawls over two historic sites with hundreds of artists represented. The main pavilion alone houses old, young, dead, unknown and iconic talents in a super-curated exhibit that aims to embrace, um, all of humankind in one form or another. The art media coverage ranges from breathless praise to bald-faced cynicism and everything in between. The mainstream media, typically clueless when it comes to highbrow art, found examples of things to understand, an heroic effort to identify a coherent thread. Which we really could not.

This is not to say that the Biennale isn’t enjoyable. It is. You might call it only occasionally humourless, taking itself very seriously, bereft of wit. A sign of the times. It’s like a treasure hunt, trying to find new twists on oft-trod ground. In prior years, our coverage pointed the accusatory finger at cavernous dark spaces filled with echoey avant-garde sounds, pretentious video installations, expansive weavings, sculptural statements rendered gigantic, and the great thematic equalizer: repetition. All that is still present. But three days wandering the Giardini and Arsenale offered up some surprising discoveries. Like Heraclitis famously remarked in 500 BC, ‘Man moves much earth to find gold.’

Speaking of gold, the Biennale jury awarded Australia’s Archie Moore the Golden Lion for a monumental genealogical chart—rendered in white chalk on black walls—tracing his Kamilaroi, Bigambul and British ancestry going back 65,000 years. As installation art goes, it delivered a powerful statement about heritage not easily eradicated by the brutality of colonialism.

The lines stretched back into infinity for the very well received United States Pavilion, where Jeffrey Gibson mounted a highly praised solo exhibition. Gibson, a member of the Mississippi Choctaw Indians, shows psychedelically coloured geometric paintings and sculptures that frequently incorporate inspiring text, integrating styles borrowed from western modernism and Native American craft. In high demand, he keeps an atelier staff of around 30 people working full-time in LA.

In the Japan pavilion, Yuko Mohri wired locally sourced decomposing produce for sound in an audio installation that reminded us that fruits have feelings, too. The electronic tones proved strangely soothing. The rest of the exhibit consisted of water-catching assemblages made from items found in Venetian retail stores, a commentary on the leaky Tokyo subway system and the scarcity of water.

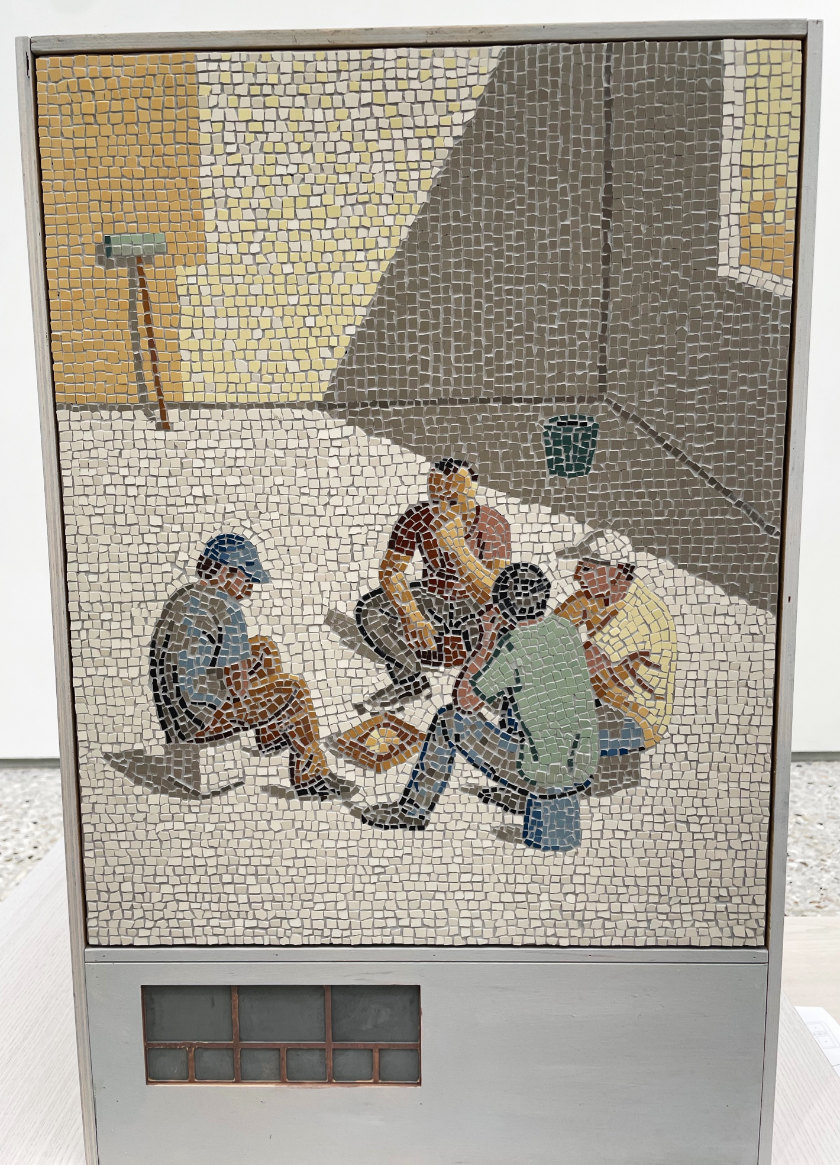

In the surprisingly enjoyable Romanian pavilion, Serban Savu showed painted scenes and mosaics of rest and leisure, reflecting on the socialist-era veneration of work, and commenting on ‘the indistinction of labour and leisure’. In a biennale short on figuration, these works really stood out for their excellence of execution.

We unexpectedly dropped into the Egypt pavilion. A filmed opera by Wael Shawky reminded us of just how good video can be when complexity, intelligent staging and affecting music combine. This artistic installation received many accolades from the world press.

Poland’s Repeat after Me video demonstrated everything problematic about video installations. Survivors of recent armed conflicts were asked to mimic the sounds of war machines. While the participants bear witness, the documentation seemed superficial, facile, gratuitous.

Outside the Scandinavian pavilion you couldn't miss a huge sculpted dragon head. Inside the pavilion a huge lattice of bamboo, much like the handmade scaffoldings seen in construction sites in modern Chinese cities, addressed the ironies of progress. Italia’s pavilion mimicked the same idea, but rendered its gigantic lattice in metal construction strut.

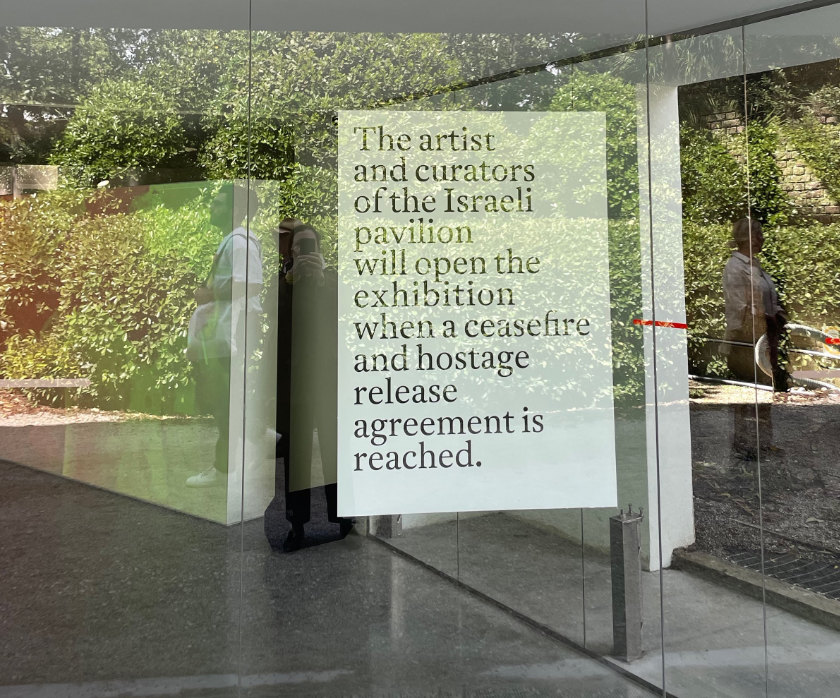

The Biennale did not escape the Israel–Hamas war. The pavilion’s curator chose to stay closed, posting a sign promising to only open its doors when a ceasefire and hostage release agreement was reached. Of course the pavilion remains shuttered. We strolled tranquilly past the entry, which sits next to the USA pavilion, where four paramilitary guards had been posted. From a distance, minutes later, we heard a crowd forming and a made-for-media demonstration happened. It did not last all that long, generated a lot of noise, many photographs were taken, and a sea of red flyers were hurled into the air en masse. By the time we got back to the site the crowd had dispersed as if never there. All that could be found in its aftermath was a sea of non-recyclable red flyers scattered on the ground.

Austria’s pavilion featured a refugee ballerina and video re-enacting another refugee artist’s first nights sleeping on benches in Vienna. This was a pavilion with artful resonance.

In the anthropomorphic department we were pleased to see the actual Refugee Astronaut by Yinka Shonibare, which played well in real life. Another mannequin attired in LED looked like fun, the kind of object which might be seen in department stores, making its point about dehumanization. The hardest working man at the Biennale could be seen wandering among the entry lines at Giardini every day. The strange sculptural cartoony figure blowing fragrance out of its mouth at the olfactory-themed Korean pavilion attracted a lot of attention.

Within Arsenale’s many vaulted chambers, installations are the order of the day. The recreation of studios was seen more than once, and some large constructions—more commentary on scarce resources. These grand chambers are ideal for monumental murals, large scale light and video installations and showcasing of textile work. A huge circular Disobedience Archive of videos demanded far too much of our time. Who wants to look at so much dark matter in a world already full of struggle and pain?

Arsenale was frequently the site of enthusiastic, overly loud echoey performances. There was little reason to hang around when you are being blasted with distorted percussive ethnic music and later suffer hearing loss. Still, many visitors came face-to-face with illuminating takes on costume and style.

Repetition, the last refuge of scoundrels, figured in an installation of neon in the dry docks. It could also be seen in the many variations of the biennale tote bag and T-shirt on offer in the gift shop. Very decorative, light on message.

Our favourite souvenir was the counterintuitively legended commemorative watch from faithful sponsor Swatch. Wear it and you’ll never forget you’re an outsider. Nor will your friends.

Kudos to LA artist Lauren Halsey for an installation of columns next to the dry docks. These celebrate local south Los Angeles heroes, using graffiti motifs and expert sculpting. It wasn’t about foreigners at all, but it did reference heritage and reminded us that community is one of the forces that helps humans feel less like strangers. •

Stanley Moss is travel editor of Lucire.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

A sidelong look at the 2024 Venice Biennale

Stanley Moss noticed the fashion at the Biennale di Venezia, and says it’s reflective of the polarized world we live in

Photographed by Gioia Meller Marcovicz

La Biennale di Venezia introduces 60th exhibition: Foreigners Everywhere

Stanley Moss attends la Biennale di Venezia’s opening press conference, with a preview of we might expect beginning April 20

Return to the Biennale

Stanley Moss returns to the Biennale di Venezia, spending three days at the 2017 event. While many countries excelled, some exhibits left question marks

Photographed by Paula Sweet