Living

The Dandi March, popularly known as the Salt March, also called the Salt Satyagraha, began on March 12, 1930. It was an organized protest against the British Raj’s monopoly, which was first legislated in colonial times by the Salt Act of 1882. Gandhi’s march continued for 23 days and formed a crucial part of the Indian freedom movement. Gandhi led his followers south from Sabarmati Ashram, his base near Ahmedabad, to the sea coast near the village of Dandi in Gujarat, a distance of 240 miles. Along the way, Gandhi continued to meet and address people. Growing numbers of Indians joined him. It sparked large-scale acts of civil disobedience by millions of Indians and changed world attitudes about independence from Britain. In the process, Gandhi was arrested in May 1930, but later freed. It established the use of non-violence as a technique for fighting social and political injustice. It’s credited with inspiring the American civil rights activist Dr Martin Luther King, Jr.

This excerpt from Becoming Gandhi describes Perry Garfinkel’s effort to retrace Gandhi’s steps 93 years later—his book is released today and available here

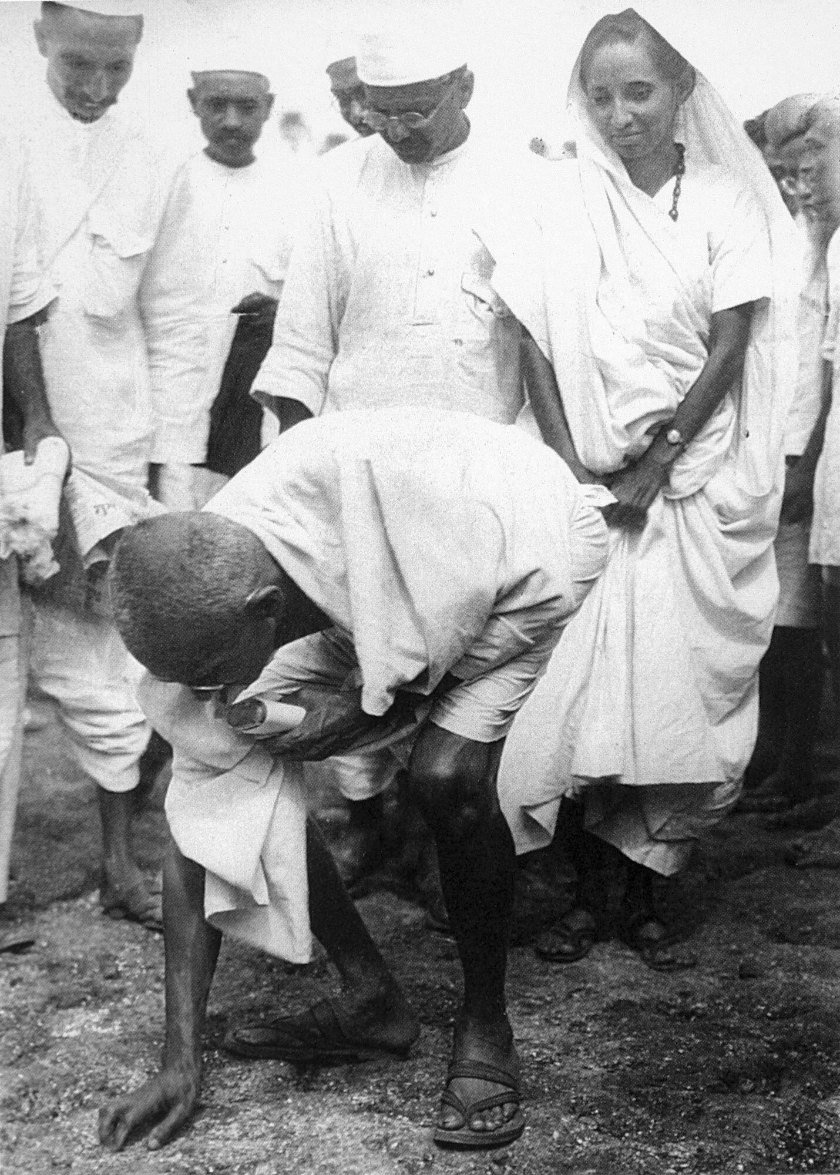

Top: At completion of his walk, the author reaches Dandi Beach. Centre: Gandhi during his march. Above: Gandhi on the Dandi beach collecting salt, an illegal act since tax was not paid, cause for arrest in 1930.

The months, even years that I built up in my mind had finally arrived: to begin the Salt March. I was both excited and anxiety-stricken. It turned out to be more and less than my expectations.

The months, even years that I built up in my mind had finally arrived: to begin the Salt March. I was both excited and anxiety-stricken. It turned out to be more and less than my expectations.

My escort-cum-expert was Debashish Nayak, an Ahmedabad-based colleague, who has been involved in managing urban conservation issues in historic cities both in India and abroad. He was director at Ahmedabad University’s Heritage Management Centre. He had made it clear to me that not only was it fairly impossible to follow Gandhi’s exact route due to the build-up of infrastructure—buildings that blocked the original path, highways that paved over his path, the crazy traffic that made it unsafe—but also that I would be unable to replicate Gandhi’s march with any kind of verisimilitude. Further, he convinced me it was unsafe to walk alone in these times. And who would want to do the walk with me anyway? Some friends had made sounds like they would, but logistically that was impossible, too.

Even Gandhi did not walk alone. I had miscalculated how long it would take me and still keep to my schedule of next adventures and flights. So I made a compromise. Day 1 I would go by car with Debashish and his team from Sabarmati Ashram past the first place Gandhi stopped and continue to the second night stop where we would meet a group of Gujarat Vidyapith heritage management students studying the Salt March. That seemed interesting. As soon as we were on the road for 15 minutes, I saw what he meant: among foot traffic, motor rickshaws, vehicles, buses, trucks, wooden carts, bicycles, cows—just a normal array of street life in Indian cities—I would have been at risk with each step. It would have been nothing like what Gandhi experienced. From there I would proceed with Debashish and team in a vehicle; they would let me out of the car to walk alone for miles, and meet them again at the far end. In villages where Team Debashish was conducting research, we’d disembark, walk by foot and then jump in the car for the next stretch. Then repeat the drill. This way I could cover the whole Salt March and see what there was to see. I did feel a bit guilty after building other people’s expectations—and my own—when I said I was ‘doing the Salt March’. But I quickly overcame my guilt.

Along the way, I marvelled at how differently Debashish worked. He was part-detective, sociologist, gumshoe reporter and community builder; part-anthropologist, archæologist, and architect; part-historian, psychologist and city planner. It reminded me of the many hats we journalists must wear.

But he was not a walker. He joined me for one stretch and I could see we did not match: he preferred to stroll while I walked at Gandhi’s pace—in other words fast. Strolling through a village was fine, as there was much to stop and study in minutiæ that I would never have picked up—rooftops, archways, doorknobs, window frames. He’d stop in a tiny plaza and paint a picture of Gandhi standing on a balcony and speaking to a small or large gathering. After three days it became hard to keep track of which village had what and when.

Nevertheless, there remain a few moments that I know will stay with me a long time.

I was left off on a small road in the countryside to walk alone. In India it’s nearly impossible to stand anywhere and be in complete silence. Yet there I was, and so stunned by the sound of nothing that I stopped and started recording me talking to myself, holding my phone mic in the air, whispering, ‘Can you hear that? Me neither. That is the sound of silence … in India! I can only imagine that Gandhi might, just might have had some similar moment in 1930. I hope so!’ Those moments of silence were often interrupted by a motorcycle speeding by, or the white noise of high tension wires. So I’d interrupt my taping until another minute of silence came around again.

Another realization came at a juncture when I was walking alone. I am, by nature, a loner. I feel entirely comfortable being just me with me. Indians are very rarely alone. Family and friends and others are always around. They seem to enjoy the tumult and chaos. If not enjoy, at least one can say that is the condition to which they are accustomed. ‘Joint family’ means parents live with their kids, their own siblings, their kids’ wives and kids, sometimes 12 to 15 bodies under one roof. I once told an Indian friend if Americans generally lived like that, they’d have to reserve a separate room for the family therapist. Gandhi never walked alone on the Salt March. He travelled with about 80 constant followers. When he left one village, the villagers followed him halfway to the next village where the group was joined by the next village while the previous villagers peeled off and went back home.

It was another stark moment to realize that while I could try to become Gandhi, I would never “be” Gandhi, nor would I want to be.

The night stops had been organized by a company that specializes in events. The accommodations were, to be kind, rustic. A step up from country cabins, they did not have great bedding. The meals, prepared in someone’s home kitchen, were brought to their guests in a common dining room. I worried about sanitation. I could not envision foreign visitors who were above the grade of backpackers.

The last 13 miles of the march were most memorable. I’d broken off from Debashish to travel at my own pace to the “finish line” at Dandi Beach. Even then my very protective driver Vijay insisted on travelling behind me in a car. There’s a memorial statue dedicated to Gandhi and his followers a few kilometres before the beach. I whizzed past it, so intent on getting to the sea. The great relief and release of walking the long beach to the water, stiff and tired as I was, as burning as my feet were, was one of the most fulfilling moments I’ve ever experienced.

The five-hour drive back to Ahmedabad seemed endless but the pull of a bed with a real mattress and a long hot shower made me feel like the horse that smelled the barn. Om sweet om, where it was. •

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Being the change

Perry Garfinkel’s Becoming Gandhi is a well timed book, with the author following the Mahātmā’s ways and finding truth in his quotation, ‘Be the change you want to see in the world’

Errands for the soul

Stanley Moss heads back to Varanasi, then to Amritsar and Dharamshala, where they were granted an audience with HH the Dalai Lama

Photographed by the author; audience photographs by the office of HHDL

What if there was a cancer drug breakthrough?

Physician Mary Austin tells a story about a miraculous cancer drug—which is then suppressed by Big Pharma. Jack Yan interviews her about her book, The Last Rose of Summer

Photographed by Elīna Arāja/Pexels