|

Cyril Zannettacci

THE EAST

MEZZANINE at the

Quai Branly Museum located in the 15th arrondissement

in Paris, situated near the Tour Eiffel facing the Seine River,

has been home for the L’Orient des femmes vu par Christian Lacroix

exhibition. From the moment the exhibition’s doors opened on February

8, until they closed on May 15, 2011, a number of guests went on

a magical tour. With haute couture designer Christian Lacroix as

the artistic director, along with Hana Al Banna-Chidiac as the curator,

the exhibition provided a wonderful atmosphere and ambiance for

people of all ages to indulge. The exhibition, also considered a

‘hymn to oriental women’, has an amazing display of 150 pieces ranging

from children’s toys, women’s jewellery, dresses, vests, veils,

as well as coats. Lacroix added his personal touch and created an

elegant and serene setting.

Arriving

at the exhibition, spectators start their trip from the North of

Syria, going into Jordan, arriving into Palestine and concluding

the expedition in the Sinai Desert where divine Bedouin dresses

take centre stage. The presentation commences with dark colours;

however, as visitors move further into the exhibition, lighter shades

are vividly projected. Stéphane Martin, the president of

the Quai Branly Museum, describes it as, ‘a feast for the eyes.’ Arriving

at the exhibition, spectators start their trip from the North of

Syria, going into Jordan, arriving into Palestine and concluding

the expedition in the Sinai Desert where divine Bedouin dresses

take centre stage. The presentation commences with dark colours;

however, as visitors move further into the exhibition, lighter shades

are vividly projected. Stéphane Martin, the president of

the Quai Branly Museum, describes it as, ‘a feast for the eyes.’

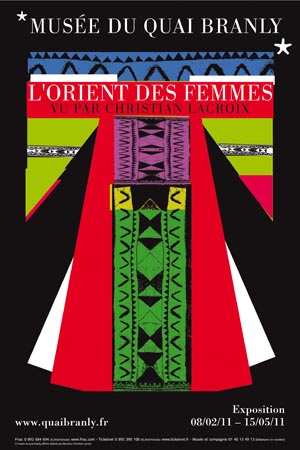

Along with the poster, the catalogue and other creative

decorations, Lacroix also designed the stunning carpet which is

based on embroidery spotted on one of the dresses on display.

One of Lacroix’s main aims is to transform the atmosphere

into more than just an exhibition but more as a fashion show; ‘a

poetic wandering’ is how he imagined the scene to be. The ‘poetic’

aspect is visually demonstrated through fashionable exquisiteness

deeply attractive to the eye. The dresses and coats are suspended

from the ceiling, as though floating in the air, providing the spectators

with the opportunity to observe each detail all around the pieces.

Viewers start to observe details along the sleeves, making their

way to the collars, and going down to the deep detailed work spotted

around the edges.

The bright colours and dim lighting rouses an oriental

atmosphere. The exhibition takes us back into time where handcraftsmanship

was more than just an artistic aspect; it was a way of life. One

of the first pieces that grab our attention as we enter the exhibition

is a child’s dress from the 13th century, found in 1991 in a Lebanese

cave (above left). The details of the stitching and patterns

create an incredibly delightful element to the eye. Wonderful innovative

features are remarkably accentuated throughout the tour.

Chidiac sat with us to discuss the work that was put

into organizing the exhibition. She enthusiastically takes us into

the beginning of the adventure, how the project evolved over time

and also explains how it was to work side by side with M. Christian

Lacroix.

Gautier Deblonde

Lola Saab is Paris editor of Lucire.

| Related articles |

|

The magnificence

of Bulgari

Lola Saab talks to Amanda Triossi, who has curated the

last two Bulgari exhibitions in Roma and Paris, with plans for

a third in Beijing

photographed by Pascal Le Segretain, Marc Piasecki and Marc

Ausset-Lacroix for Getty Images, and courtesy Bulgari |

|

The Hamptons in

Genève

Genève became the Hamptons for a night as Baume & Mercier, with

spokeswoman Gwyneth Paltrow, rang in a new era for the watchmaker.

Elle Hopper reports

photographed by Damien Keller/PhotoProEvent and the Image

Gate |

|  |

Lucire: How did the Women in Orient seen by Christian

Lacroix exhibition develop and come together?

Hana Al Banna-Chidiac: The idea of making this exhibition

was born three years ago. We have a very nice collection of textiles,

all of the dresses and even toys arrived in the Musée de

l’Homme in the beginning of the twentieth century. They were brought

by French people living there and even military archæologists

… Of course, I thought I can make something with all of these coats,

jewels, dresses, but very quickly I realized that some of the villages

of the country were missing.

This is why I asked Madam [Widad Kamel] Kawar, a Palestinian

living in Amman in Jordan to participate in the exhibition by lending

us some costumes, and she quickly gave her answer … it was a positive

answer. I travelled twice, I think, to Jordan to meet with her.

In the beginning I wasn’t sure if I wanted to just present

the costumes of the country and the Bedouin costumes ... but very

quickly I decided I wanted to show the first part …

In the big towns of the Middle East, women used to wear

dresses that looked like Ottoman, they were influenced by the Ottoman

style. First, I made a large selection of these costumes. The museum

bought costumes: Egyptian, Palestinian and Syrian; I was trying

to complete the collection. And even the beautiful headdresses,

at the end it was Christian Lacroix who made the last selection

because it was difficult for me to take away some of them. I wanted

to show so many beautiful things at the same time, but I didn’t

want to make a simple ethnographical exhibition. I had the desire

to give the exhibition an artistic dimension ...

Did you previously plan to work with M. Christian Lacroix?

You know, these dresses are no longer worn anymore by women, and,

for me, I did not want the public to leave the exhibition with a

kind of nostalgic sentiment. This is why I decided to work with

a contemporary artist. I wasn’t sure at first with whom I wanted

to work with ... Somebody who would be sensitive to these beautiful

colours—very hard colours: red, yellow, blue and especially the

embroidery. And somebody matched all of these conditions, somebody

who really likes Mediterranean arts, and, of course, it was Christian

Lacroix! We contacted him three years ago and he quickly gave his

positive answer, it was wonderful for me.

How was it to work with M. Lacroix?

It was a beautiful adventure to work with him because Christian

Lacroix is so sensitive. He didn’t just work on how the scene was

supposed to be: he also designed the poster, he was also the artistic

director of the catalogue. All of the moments spent together were

very enriching.

Could you briefly tell us a certain theme or message that you

want people to attain as they walk through the exhibition?

I wanted to give the exhibition a historical dimension because the

embroidery is an old art in the Middle East. I didn’t want people

to look at the dresses and say, ‘OK, this was just born 50 years

ago.’ No, the embroidery was born centuries ago and this is why

I bought from the National Museum of Beirut a small dress found

in a cave in the mountain of Lebanon: it was a way to show people

the old-fashioned ways of fashion design at the time.

The most important message, and really what I hoped

to offer from this exhibition, is that people don’t just look at

the dresses because they are beautiful. [Just] imagine [the women]

behind these dresses. It is important for me because they did their

best to embellish themselves, to certainly try to exist and to soften

their lives. Perhaps, I hope that when the public leave the exhibition,

if they can have another look on these oriental women, to change

[the] image [they hold of them].

Tell us about the designs that have been added in and around

the exhibition.

The first time [Christian Lacroix] came to look at the exhibition

with the president of the Quai Branly, Stéphane Martin, we

came from here [points down to the ramp that leads to the mezzanine]

and he was smiling because it is not very easy to find the mezzanine

when you arrive. Here he had this idea to hang beautiful neon light

dresses [hanging from the ceiling as it signals the way to the exhibition].

He also put around the mezzanine veils and this beautiful carpet,

which is an impression of a design featured on a Syrian dress. The

design was enlarged one hundred times.

The artistic features have been specifically worked on and personalized

according to oriental attributes and designs. For example, the poster

that M. Lacroix designed to represent the exhibition is based upon

similar colours and shapes that we find on some dresses and coats

that we come across. Looking at the poster from afar, there is a

dress that fantastically comes to life. As you mentioned, there

are the neon lights in the shape of dresses that are placed to mark

one’s way to the exhibition. How would you describe all of these

custom-made elements? How have they contributed into making the

exhibition such an artistic vision in itself?

Usually, the Quai Branly works with an agency to make all of the

posters. But for this exhibition it was great that Christian Lacroix

made all of them, because there is a kind of unity between the exhibition,

the catalogue and the poster. In terms of the poster, he understood

this geometrical constitution of the dresses: you have the triangle

and other shapes that come together. He also chose the photographer

who made the photos featured in the catalogue. I didn’t want the

catalogue to be as a normal catalogue, very classical, very ancient

… For me it is as if the dresses went out of the stores to meet

the people … they are almost flying out and coming to life. I wanted

it to be a book of art.

After the opening of the exhibition, was the outcome of its

success what you expected it to be?

It was more than what I expected! I think for me, I worked for 17

years at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and I made lots of

exhibitions, and this one is smaller than the others but … gave

me a lot of satisfaction and happiness. Perhaps because there are

women presented in the exhibition and for me it was very important

to say to people, ‘No, oriental women did not spend their time wearing

black things …’ All of the preparations of the exhibition was wonderful

with Christian Lacroix, who was really so cute, so nice and also

so elegant.

In the nomadic society and villages people did not have

closets; they used to put all of their things in a box … Christian

Lacroix designed them and it looks really like the boxes they have

in the villages.

Unlike other exhibitions, this exhibition allows people to touch

the items that are featured. Why did you decide to include a different

system in which people are free to feel and touch the objects?

It was my way to make this exhibition livable and even this idea

of hanging dresses that people can touch, it was important for me.

When you visit an exhibition usually you shouldn’t touch things

at all, but here I wanted people to touch … for blind people as

well as everybody else.

How would you summarize what the exhibition represents?

If I were to summarize the exhibition, it is mainly to change the

image of the oriental women in terms of their dresses and outfits.

This is a poetic exhibition.

Christian Lacroix came to this exhibition several times

to see it and he was very happy! He told me that he didn’t imagine

that this would come together so closely to [the] project that he

had in mind.

Will the exhibition internationally go on tour? If not, is it

something that you envision in the near future?

We were contacted by different institutions. There is one that we

are in the middle in negotiating with, one that is featured in another

continent, they seem interested, but I cannot yet provide you with

the name. We first need everything to be confirmed. •

|