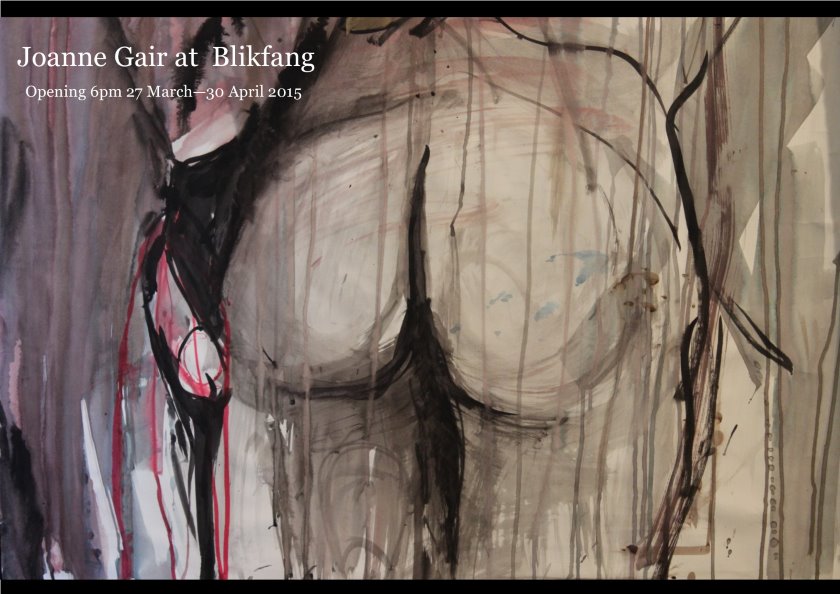

Energetic Joanne Gair’s art, showing in Auckland, reveals a very different side to the famed make-up artist

Janie Duneas is a guest contributor to Lucire.

Janie Duneas looks at a different side to Joanne Gair, internationally known and sought after for her make-up and body-painting work, on the eve of an exhibition opening of her paintings at Blikfang in Auckland

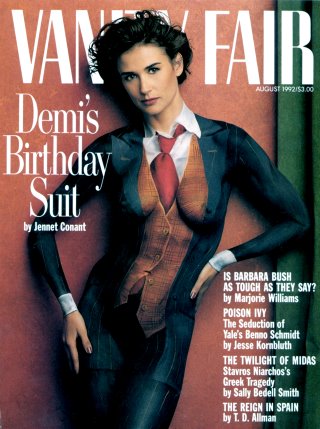

Joanne Gair, iconic make-up artist and body painter, has worked and collaborated with many of the top international photographers, directors, models, celebrities and brands. She has worked extensively in editorial, fashion and advertising campaigns and has established an important presence within her industry. Gair’s client list include Demi Moore, Madonna, Heidi Klum and Lada Gaga, among many others. One of her most recognized and iconic work is the Vanity Fair cover featuring Moore in a body-painted three-piece suit. With Madonna, Gair spent 10 years as her make-up artist on many of her famous images, tours and also music video shoots. Gair can be seen throughout the documentary Truth or Dare. Her music video work with Madonna spanned ‘Express Yourself’ and ‘Vogue’ all the way to ‘Frozen’.

In 1999 Gair’s body painting first appeared in the pages of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition. It has since been a yearly featured section for her in the magazine. A few of the models that she has worked with on Sports Illustrated include Heidi Klum, Rachel Hunter, Sarah O’Hare, Petra Nemcova, Chrissy Teigen and Kate Upton. Recently, Gair’s body painting appeared on the cover of the regular edition of Sports Illustrated featuring baseball player Giancarlo Stanton. This body-painted cover was a first for Sports Illustrated. She also had the opportunity this year to design multiple looks with a large cosmetics company in a branding campaign that is due out later in the year. Gair’s creativity, her experimentation, mastery of her medium, and conceptual interpretations have established a strong and successful career. She considers herself an image maker, and her work on paper is now an extension of her body painting.

Substituting for the body, Gair is here working directly on paper. Contrasted with the meticulous trompe l’eoil detail that she achieves on skin, her ink drawings of bodies on paper are a vigorous outburst of line and tone. In her profession, her artistic concerns are tactile; the body is alive, breathing sweating, tightening, and the surface of the skin changes from limb to limb. To achieve her illusions, she has to consider textures, tones, and the qualities of the cosmetics she uses to achieve the desired effect depending on the exposure that the painted body will receive. Hot, cold, in water, over sand, each environment will require specific resolutions.

With her familiarity and appreciation of painting on the body, Gair’s work on paper continues her theme of bodily representation. Not only does she grasp human anatomy, she also understands how it moves. Gair explores how bodies portray emotion, reflect interpretations of intimate moments and provocative movement. On paper she expresses a freedom of form that is in contrast to the fine detail of her make-up practice. She says that when she works with a medium, for example, ink, the medium, like the living body, expresses a life of its own. Its fluidity encourages her to work more spontaneously, with big, fast movements; it takes an energy, rather than conscious effort. The character of her medium affects her expression and approach, resulting in an eclectic layering of textures, colour and lines. Gair’s dynamism is reflected in her paper works. She says that she is encouraged by the fact that she, and her environment, is constantly evolving and in flux rather than stagnating in conformity and the security of familiarity.

The history of skin adornment often reflects the “earning of one’s stripes”, or commemorates a moment of tradition, lineage, ritual or passage. Adornment of the skin, through make-up or paint, provides the opportunity to encompass later change. Your look can be altered to reflect your mood, your agenda, and your identity. She is well aware of the ephemerality of existence. Living in New York, she says that aura of the streets invades the environment. The excitement and pace of movement, the visual delights that are so readily available to intoxicate the senses, Broadway on your doorstep, art galleries, street performers, heritage, culture and soul, it’s all there in New York to be consumed and to consume you. In her desire to follow a creative journey, Joanne Gair has found New York to be her ideal creative placenta. Although she still gets very homesick and each return to New Zealand is profound.

Her New Zealand origins have, nevertheless, been important. She says that the Māori culture of tattoo and dress, their adornment of skin, has revealed to her the power of transformation as an ‘expression of maturity of thought’. She is also very in touch with the primal and pivotal awareness of the body and how we adorn or fashion it. The body has been shaped and hidden by “culture” and polite society, by trends, times and circumstances. But Gair has a blatant and feral acceptance of the body, akin to primitivism in western art, explored by artists like Picasso, Klee and de Kooning. It is this confrontation and unapologetic familiarity with the body that Gair uses as a vehicle of experience and thought in her work on paper. Most philosophers before the idea of phenomenology, the study of experience, were occupied with issues to do with thought or the mind, ignoring our bodies as vehicles to actively extend and transfer thought. Husserl and Merleau-Ponty, for example, considered the body as a subjective, sensory flux. They asserted that immediate living proceeds from the body and the way in which we measure the world, therefore environment is measured by the situation and appearance of the body in the world.

In Phenomenology and Perception (1962), Merleau-Ponty analysed the manner in which our body provides us with a ‘corporeal and postural schema’ within the world as we know it. It centres our awareness of space (up, down, left, right) which is formed by a self-body reference. We think with our bodies, connected to our brains through the nervous system. Our consciousness is both body-oriented and body-involving. Gair’s work, primarily body-centred, manages to create an awareness not only of how other minds envision bodies, but how we can begin to see and feel our own bodies through the interpretations of others. The body is a continual rotation of associations and comparisons, male, female, child, disabled, abled, genetically enhanced, and desired, a nervous system, and a chiasm of touching and being touched, of affecting and being affected, of ageing, of progression and decay. In this way art, and the bodies that Gair paints, generate a brave awareness of the body as a conceptual vessel that can project various thoughts and feelings, often provocatively. •

Joanne Gair at Blikfang, from March 27 at 6 p.m. to April 30, 2015

Blikfang

130 Queen Street (corner of Clarence Road)

Northcote Point

Auckland

Telephone 64 9 480-1795

Open Wednesdays to Saturdays inclusive, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Olga Lomaka: Parasites of Consciousness

Olga Lomaka: Parasites of Consciousness

London-based artist Olga Lomaka brings femininity and sexuality into her work, bringing dreams and fantasies into reality. Elina Lukas speaks to her on the eve of her new exhibition

Phil Stern: from shadows to enlightenment

Phil Stern: from shadows to enlightenment

The renowned photographer celebrates his 95th birthday and career with the opening of a permanent exhibition at the Veterans’ Home of California. Elyse Glickman reports

photographed by the author

A new take on Newton

A new take on Newton

Lola Saab attends the Helmut Newton exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris, the first retrospective held in the city since the photographer’s unexpected death in 2004

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.