LIVING Lola Cristall finds out more about the field of music supervision, talking to Thomas Golubić, president of the Guild of Music Supervisors, after attending their ninth awards’ show in Los Angeles

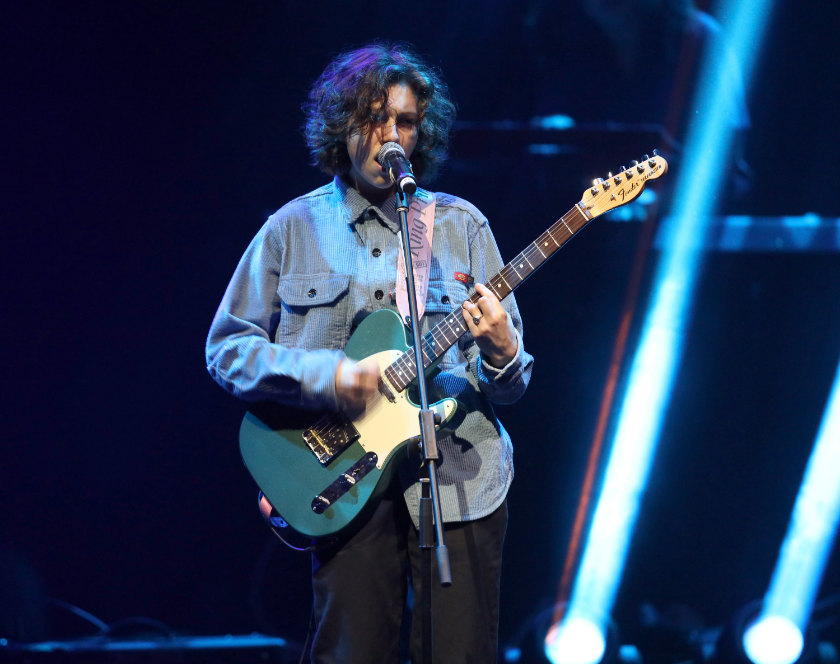

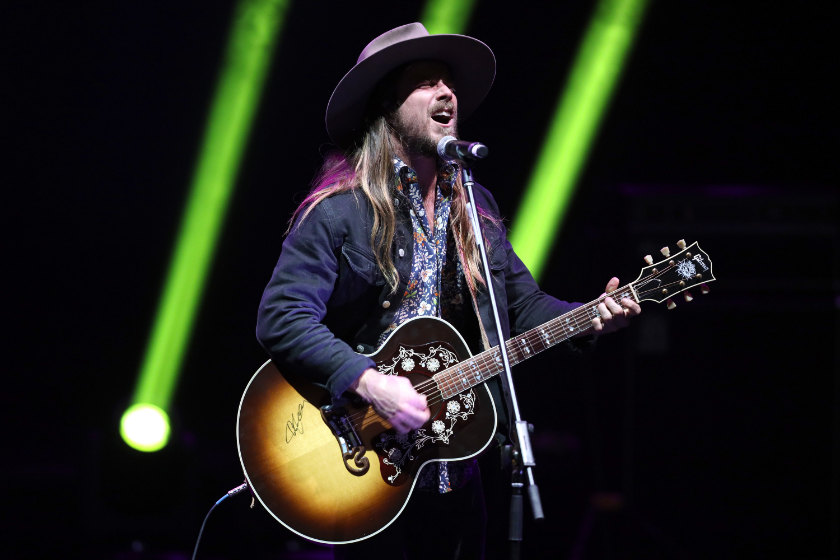

Photographed by Rich Polk, courtesy Getty Images on behalf of the Guild of Music Supervisors

Guild of Music Supervisors’ president,

Thomas Golubić

Lola Cristall is Paris editor of Lucire.

The Guild of Music Supervisors is a non-profit organization that is concerned with the creativity, the art and meticulous detail in the field of music supervision. It recently hosted its ninth annual awards’ show in Los Angeles with guests including Macy Gray, Gloria Allred, Linda Perry and Anthony Anderson. Marc Shaiman, Lukas Nelson, King Princess and Aimee Mann performed on the vast stage. Shaiman was honoured with the Icon Award and Joel Sill with the Legacy Award. The evening celebrates music supervisors in various categories such as film, television, trailers, games and advertising. We spoke with the Guild’s president, Thomas Golubić, a highly talented and deeply passionate Emmy-nominated music supervisor whose endless list of credits includes Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, Six Feet Under, The Walking Dead and many more renowned television shows. He explained to us the savoir-faire and methods applied to music supervision, while also revealing how some of his previous projects were put together, and what we can look forward to in the near future.

Can you define the role of a music supervisor?

There is an excellent definition on our website … In essence, the music supervisor is the head of the music department for any film, TV, ad or video game … any media project. Their role is to essentially guide the storytelling process as it applies to music. So if somebody, for instance, is writing a screenplay and they're looking to have it turn into a film, at some point in the production process, if it has music as the major component, it is likely to hire a music supervisor to help lead that process in the storytelling. That means the supervisor meets with the creators, the storytellers themselves, the writers, the directors, the producers, gets a sense of the story that they’re looking to tell, sends different options of how music can aid that project of the storytelling device. That means the music supervisors are responsible for being able to read scripts, understand storytelling … and then also discuss with those producers budget, schedule, and create essentially a presentation of ideas of how they can proceed to make the most of music for that project.

As a non-profit organization, the Guild of Music Supervisors is all about promoting the art of music supervision. Can you further describe the role of the Guild?

The Guild of Music Supervisors previously were a very … loosely affiliated group. We barely knew one another, we were all dealing with individual challenges where we were not often not preparing notes or supporting one another. I think there was generally a problem [where] folks didn’t understand what music supervision was, and that includes producers, directors and studios, so we were frequently undervalued … We were frequently overworked and we were very rarely able to support one another as a profession. So the Guild formed about nine years ago to basically try to address those issues: to address the misunderstanding of what the job is, to try to clarify what the responsibilities are, to bring our community together to work together towards better practices, smarter approaches, sharing of resources, building a community where we all are able to support one another as we go through this rather difficult and very challenging job. We also work very hard to raise the standards of the profession and to give individual music supervisors and members of our Guild opportunities [to] learn, to educate themselves [and] to have resources available … We have an annual conference that we do and multiple educational events throughout the year and we also establish [the annual award show], which has now become obviously a very big deal, celebrat[ing] music supervision and the emerging of music and media together in the creative art.

continued below

Would you say it’s a considerably tight-knit community?

We’re developing it … Music supervision, unlike other professions, doesn’t have a clear pathway. If you want to be a film director you, generally speaking, go to film school and you focus on film directing and you navigate accordingly. So those folks know each other, they come up together and I think that the Directors’ Guild is a much more tightly knit group simply because of the much more narrow pathway developed in their career path. Music supervisors, we come from many different fields. I came from public radio and went to film school, others come from record labels or from music publishers or licensing companies. People come from many different standpoints, so we believe that the Guild is a meeting point where all these different pathways begin to converge and help to cultivate better work amongst the music supervision community and better support for one another.

While the Guild of Music Supervisors is about recognizing the talent and work of music supervisors, it is also about spreading knowledge and educating future music supervisors. What are examples of methods and techniques that are shared amongst music supervisors?

It’s an exceedingly complicated job in the sense that you’re dealing with a creative contribution and having the sensitivity to understand how music can effect storytelling, can effect emotional feelings and audiences. You have a business component, in a sense: people have to know how to operate and run their own business. Most music supervisors are independent and are working independently, they have their own companies. You have to also be able to view the business side of the process, meaning developing relationships with different licensing companies, publishers and labels, and being able to clear songs, knowing the nuances of the legal language that’s part of it. You’re in many ways ahead of the business component of the clearance process, which means you’re guiding a production in what are feasible approaches to being able to license the music for their project. If somebody comes in and says, ‘I want all James Brown songs, but I don’t have any money,’ you have to find a way to be able to say, ‘Well, this might be doable but only if we are able to do it the following pathway.’ That means you have to have knowledge of how to navigate that relationships with different people involved … people don’t realize how difficult it is to clear music, how obscenely expensive it can become, and without a music supervisor to lead that process, it can frequently become the most frustrating part of production … From diplomacy, the ability to work collaboratively in groups, to lead a team to be able to have a sensitivity of being able to guide your colleagues, whether it be music editor and helping them in the edits that they’re doing, whether it be a composer to help navigate through a difficult part of the pathway through their composition. It could be also navigating songwriters in the process of creating songs in the different projects or soundtrack partners in building soundtrack albums. There’s many different partners that music supervisors have to interact with. You have to do so with both a sense of diplomacy and also a sense of clarity, so you have to communicate well, you have to be diplomatic in how you work, and you have to bring everyone together behind the vision of filmmakers, and that can be a very challenging enterprise.

Generally speaking, how long would a project take to put together?

It depends on the project. An advertising project could be anywhere from a one week turnaround to being an entire year of development, depending on the complexity of the project. Film can be anywhere from a few months to multiple years. I’ve worked on films for three or four years at times … In many ways, the music supervisor’s goal is to work with the time schedule and be able to strategize accordingly …

Every project is different and every window of time is different. This also becomes a major issue when it comes to paying supervisors because frequently supervisors are paid a very low fee for a very long production window, and so part of what the Guild is trying to do is help supervisors get a sense of what are appropriate fees and how they can navigate that and to some degree also educate the community as a whole about what our job is … People have a sensitivity towards what is actually involved, they’re not just throwing out random numbers and they’re not trying to get as much as they can for as little as they can, but recognizing that there is an art and craft to the profession and that having a strong supervisor who is able to really focus on your project is a really valuable commodity.

You have a number of credits that include Six Feet Under, Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead, Better Call Saul and many more. How do you know what kind of music to incorporate according to the story and characters? It is said that you create ‘mix tapes’ for each character, can you elaborate?

It is a very collaborative effort … When I work on any project, I look for what makes that project unique and I discuss with the filmmakers what it is that they’re trying to express and how we can possibly do that. Some of that is them telling me, and some of that is me suggesting to them. [There are] different factors, depending on the project. In the case of Breaking Bad or Better Call Saul, we have the same team on both projects, which is wonderful because we’ve been working together now for over a decade, but at the same time we did a very different approach to Better Call Saul than we did to Breaking Bad … That also applies to Dave Porter, the composer: he has a very different palette of sound and in many ways a very different approach to the project.

Every project is very unique. Six Feet Under was very much about a Los Angeles-based family-run funeral home with younger people, meaning people in their 20s, both a teenager as well as two brothers in their early 20s, you’re able to explore music of their generation. We also had the mother Ruth, who is in her early 60s, [there was] the ghost of the father and his sense of music and the many different characters that were introduced into the story, so we were able to explore, Gary Calamar, partner and I, many different approaches to music …

It was perfect for us, too, because we both came through KCRW, which is a radio station here in LA, and [we] would be very much in the pocket of the character’s listening experience. We were able to explore music [that] we were already listening to and playing on the radio, into that show as was appropriate and we were very much learning about storytelling since early in our careers. As it came to Breaking Bad, we had a completely different location, very different story in Albuquerque, New Mexico. I took a trip out, when I was first hired, to Albuquerque and literally sat in everything from bodegas to little taquerias, to convenience stores, to warehouses, every place that could possibly have music playing. Whether it was music for workers, whether it was music for customers, whether it was music that was just playing in a cab as I was driving around, it really gave me a sense of what the sound of Albuquerque was … Helping to stitch a palette of sounds and ideas that were, for me, what I thought Albuquerque could be, so we could give it a reality and give it a consistency … You really had a sense of time and place with music even in the subtle background. That was a very different kind of project.

Then there was Halt and Catch Fire, a 1980s-era story about technology, and we had very kind of avant-garde, forward-thinking characters, and we were able to delineate each one of them individually, into very different people and tell their stories with their own relationship to music. It was a very exciting opportunity to kind of explore these different worlds and go through a huge selection of music, that I have, and my team has, to try to find the best ideas to articulate the story as we could.

Every project is radically different from the other, that’s one of the exciting things about music supervision, you’re never doing the same thing twice. You might have similar approaches, you might be reaching out to similar companies or colleagues for clearances and for licensing and creative ideas, but the truth is that every project is unique. And the more you can empathetically channel the characters of a story, the more you can get a sense of the tone of the personality of the project, and in many ways, the creative leadership that are leading that project and their sensibilities, the more effective you can be as a music supervisor. You have to bring all those elements into one equation and then find a way to make that work … so it’s an interesting mix of business and creativity and being able to really tell stories with music.

Have you noticed a considerable evolution in the field of music throughout the years?

Absolutely, I think the greatest change is technology. Technology has changed everything in the last twenty to thirty years … When I was in high school, and was really obsessive with collecting music, I would have to take a 20-minute walk to get to a bus to take a 45-minute bus ride to get to a train, to take another 30-minute ride into the city to go to the record stores that would have the music I was looking for … I was collecting vinyl, there was no real way of being able to listen to a few things here and there hoping that it [was] good. Then doing the exact road back to just figure out if I even liked what I got. You think about the amount of investment that goes [into it] … It gives you a sense of patience and it gives you a sense of curiosity … even just putting a needle on a record, the time it takes to get up and change the record motivates you to be patient. Whereas now, you literally click a button and change to the next song, you have almost the entire collection of recorded music available to you digitally, which changes the equation dramatically … It has also dramatically devalued music, because now people are able to access everything for free, or very inexpensively … So these overpriced pieces of plastic, that used to be what the music industry ran on, are no longer a valid business model. In many ways, we hope that listeners will be respectful of the work that goes behind it and will financially support the artist … There is many other avenues to supporting music, but it is, in many ways, a more voluntary effort … so that has changed dramatically.

Are there any particular projects that you are currently working on?

We are right now working on a few projects, we are working on Better Call Saul season 5, we’re just preparing that … We got a sense of the general art of the story, a little bit of the sense of the evolution of the characters. Our next role now is going to be building more of the ‘mix tapes’ that you mentioned earlier, being able to get a sense of potential direction that the writers, the editors and the directors of the episodes would take …

We’re working on Grace and Frankie season 6, which is a wonderful comedy with Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin. We’re working, right now, on setting the palette for that show. We just wrapped up on a show called Sneaky Pete. We have a couple of film projects that are in the works that I cannot speak about yet. We’re busy, we have lots of different projects going on at all times, so there is always a sense of new and exciting adventures ahead of us.

What does it take to professionally acquire the techniques and methods in the art of music supervision?

I would say perseverance is certainly one of them. It’s a tremendously challenging job, it requires, as I mentioned earlier, a number of different skill sets. It requires, I think, the ability to recognize that you’re never going to get rich doing it … you have to basically enjoy and love the work and be able to really focus on a daily basis and put all your passions and excitement into the work. I think, it’s like any job ultimately, the people that do the job best are the ones that really love it. If you love listening to music, if you love watching films, reading scripts, really focusing on storytelling and thinking [of] how it works, you will get better at it with every effort, so it’s the people who love the work the most that, I think, are the most successful at applying the craft of the profession. •

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

Awkwafina: working among crazy rich Asians

Rapper and actress Awkwafina plays Peik Lin in the summer hit Crazy Rich Asians. We sit down with her to ask about her experiences on the film, whether she saw any real-life crazy rich Asians, and what it was like working with Constance Wu and director Jon M. Chu

Hear her roar!

Hear her roar!

Award-winning documentarian Leslie Zemeckis returns with a film about Mabel Stark, another fierce and fearless Hollywood trailblazer, writes Elyse Glickman

Gal Gadot makes waves

In another look back through our first 20 years, Jack Yan spoke with Gal Gadot in 2009. Back then she was beginning to make a splash in Hollywood, years before she was cast as today’s Wonder Woman. We had the foresight to put her on the cover

Photographed by Andrew Matusik

Hair by Jonathan Hanousek/Exclusive Artists

Make-up by Elaine Offers/Exclusive Artists

Styled by Cliff Hoppus

Digital post by DigitalRetouch.net

Photography assisted by Kirk Palmer

From issue 27 of Lucire

Advertisement

Copyright ©1997–2022 by JY&A Media, part of Jack Yan & Associates. All rights reserved. JY&A terms and conditions and privacy policy apply to viewing this site. All prices in US dollars except where indicated. Contact us here.