The 1964 Ford Thunderbird: an early appearance of the fake landau roof.

FASHION Two years ago, we drew parallels between modern design trends (and economic events) and those five decades ago. If that is true, then what is around the corner? Jack Yan peers into history

AmFAR

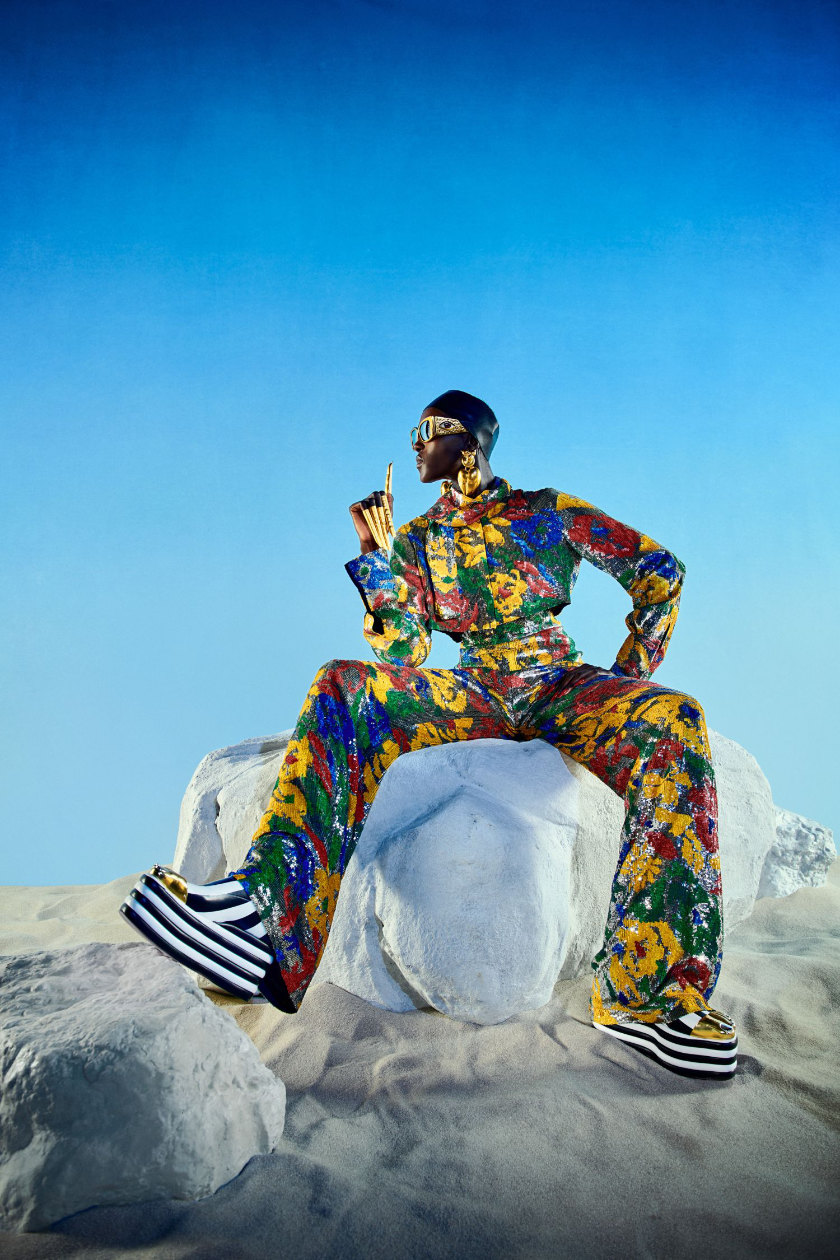

Bright colours from Valentino for autumn–winter 2022–3, and Schiaparelli for spring–summer 2022. Above: Eva Longoria in

Mônot and Cartier at the AmFAR gala.

In 2020, we publicly advanced the thesis that tough times were coming, though we waited till the pandemic had become a reality before our story was published on our website. I had privately mentioned it in social media, though it’s a little difficult to claim to be prescient when most people could have, by April 2020, predicted that COVID-19 would have an impact on the planet.

In our case, since this is a fashion magazine, it was examining trends, and noting the parallels between the early 1970s and today. In October 2021, we made some comparisons in Lucire KSA, looking at how to appeal to young consumers by seeing what history told us. The earlier 2020 story, however, started with something rather esoteric: small car windows.

Just as some have the hemline theory (the higher the hemline, the more buoyant the stock market), we have the window theory. The US, which led this trend, began by selling glamour in addition to practicality, something they have done in the automotive market since before World War II. But this trend led to ever-larger swathes of vinyl applied to the metal roofs of cars, in an attempt to ape the hoods of horse-drawn carriages, even though these car roofs did not fold down. Although the idea probably came from Ford in 1963, with its Thunderbird model, it really took off once the 1970s started. Detroit could not sell performance due to the changing regulatory environment, so it sold faux luxury instead, and this filtered through to other parts of society. Wide lapels, flouncy fabrics, porcelain make-up were its parallels in fashion and beauty.

Rather than examine what consumers really wanted, the established players served up more of the same, in extremis. Good design became garish. And when the next economic shock happened in 1973, with the Arab–Israeli war, petrol prices soared, and suddenly Detroit was left in the position of the emperor with no clothes: big cars were something no one truly wanted, if a small economy model from Toyota, Nissan, or Volkswagen would suffice. In the west, inflation understandably followed.

It is not the task of this title to examine geopolitical conflicts, though it is easy to draw parallels with the period. When we published our story in 2020, we alluded to the fuel crisis, and it’s tempting to equate Detroit’s big cars with modern, inefficient SUVs. Except this time, the Japanese are making them, too, as is Volkswagen; it is probably no surprise that the Tesla Model 3, hardly the newest design, nor one that is affordable for many families, did brisk sales in 2021.

Where are we with fashion? The Cannes catwalk showed more revealing outfits than ever before, with plenty of eye-popping colour. It’s mirrored in Tiktok, with users brightening up their followers’ days with colour. We see it in Instagram, and we see it in youth culture, with what Shein’s been serving up—questionable its policies may be, but it shows where trends are.

Once again we have some parallels with the early 1970s: having cast off the purples, oranges, browns and yellows that started the decade, designers went to great lengths to do something to make their mark. The 1960s’ trends exhausted, where should they head next?

In 1973, le Grand Divertissement à Versailles—later known in English as the Battle of Versailles after the press declared it one—saw five French couturiers show their wares, along with five invited American designers. On the French side were Pierre Cardin, Marc Bohan for Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent, and Emanuel Ungaro. On the US side were Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Halston, Anne Klein, and Oscar de la Renta. The purpose was to raise funds to restore the château.

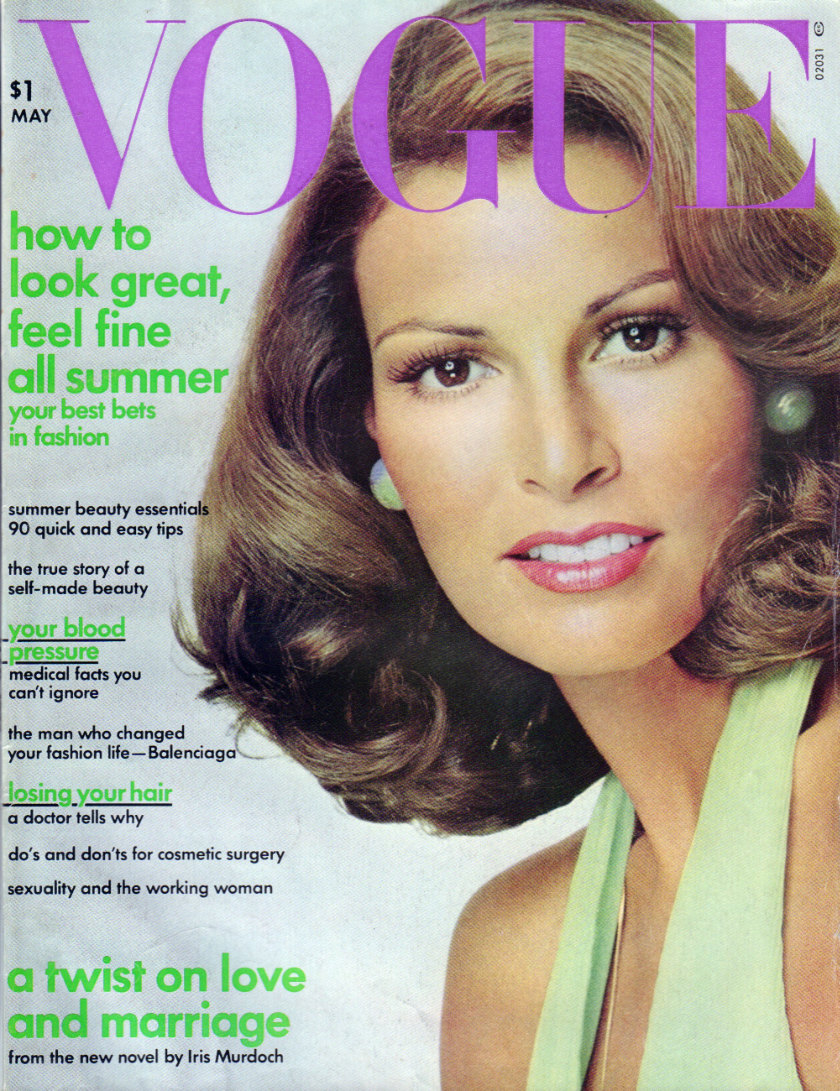

With hindsight, battle is probably not an inaccurate word, for the contrast between the nations was clear: the old world’s class system versus American meritocracy; the art of couture versus the US’s commercialism; and the all-white French designers’ line-up versus the US’s diversity (Burrows is black, as were 10 of the 36 US models). Trend-wise, this was a night of colour, with the Americans using the brightest shades—red, green, yellow, and blue—to signal their arrival and a sense of fun, and history generally regards the visiting underdog to have “won”. The effects of the Battle of Versailles continue today: in Europe, it signalled that US design had arrived. Nowadays, however, one has to ask if the US is the hierarchical establishment that needs to face a challenge. From where will the new meritocracy emerge?

It was a turning point in trends, giving the western public some optimism when things were uncertain. The heaviness of 1970 began shifting in favour of lightness. What also occurred around this era, trend-wise, was a greater embrace of the efficient: self-sufficiency with growing your own food became trendy, cars’ window areas (that again) grew once more since it let light in to cabins, and rational, modernist product and graphic design became stylish rather than experimental. This was an era of ItalDesign, the Trimphone, and the jumpsuit. A women’s trouser suit became acceptable. Straight lines were more trendy than curves since they conveyed volume and modernity, even if we had to suffer through the era of flared trousers. We can only hope that 2023–4 will not be this garish, but early signs are promising: Chinese electric cars such as the IM L7 have a simple, efficient æsthetic.

You could argue that this theory has no real connection to economics; that things are simply cyclical and when one trend is exhausted, another must necessarily pop up. Maybe. But we might respond: would a trend be considered exhausted if the public is quite happy to stumble into more of the same, in a desire to tell themselves “everything is normal” when clearly it is not? Historically, we did that till the events of 1973 shook so many out of their slumber. This time, we might even realize just what is systemic in the occident, leading us to such a similar point in the economic and trend cycles again. Can that, too, be given a good shake so as humanity we can really advance together? •

Above, from top: Vogue’s May 1974 cover: colourful clothing and type. The 1974 Volkswagen Golf. The 2022 IM L7 electric car from China.

Jack Yan is founder and publisher of Lucire.

Related articles hand-picked by our editors

The Generation Z game

Le jeu de la genération Z

There’s been a lot of talk in marketing circles about the next influential demographic, Generation Z. Jack Yan looks at how fashion brands can appeal to them

Dans les milieux du marketing, on parle beaucoup de la prochaine génération démographique, la génération Z. Jack Yan examine comment les marques de mode peuvent les intéresser

From the October 2021 issue of Lucire KSA

Weight: a moment

The US car industry’s design excesses of the 1970s had their roots somewhere, mirroring what was happening in fashion. Jack Yan thinks they emerged during more optimistic times and history may be repeating

Enlever le pied de l’accélérateur

Les consommateurs ont beau dire qu’ils n’aiment pas la fast fashion, la réalité est que des plateformes comme Shein gagnent des millions, la génération Z constituant un marché souvent coopératif, écrit Jack Yan

Dans le numéro du juin 2022 de Lucire KSA