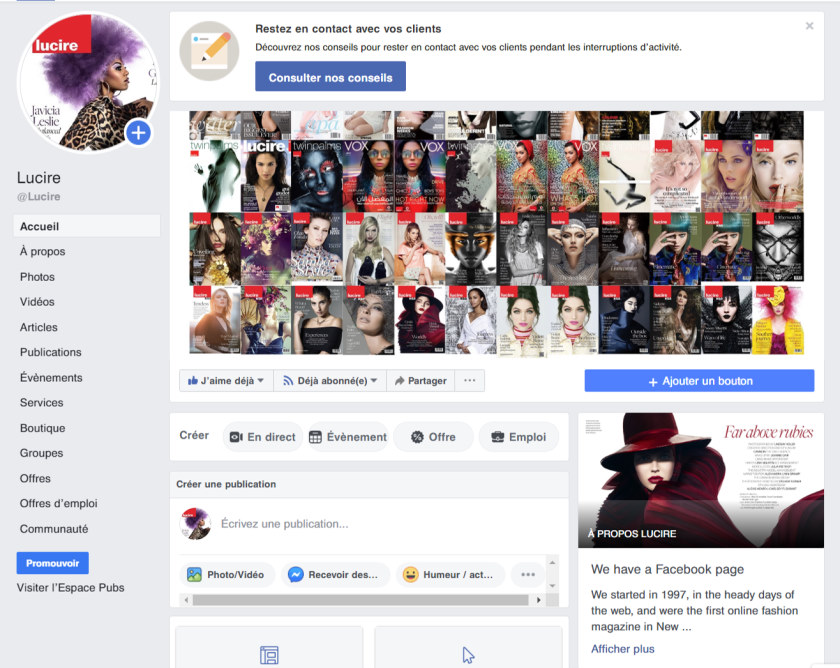

Like many other publications, Lucire sends updates to Facebook, Twitter and Mastodon. Occasionally we’ll Instagram an image to a story. However, we’ve had reservations about social media, especially Facebook, for over a decade. In November 2010, we wrote on our Facebook page, ‘We have stopped the automated importing of notes to this Facebook page. These stories receive around 200–400 views each, but that also means that our site loses 200–400 viewers per story.’ At that stage we probably had around 600 fans on the Lucire fan page, showing you just what cut-through pages were getting before Facebook intentionally broke its sharing algorithm to force people to pay to get the same reach. (Reach dropped 90 per cent overnight.) We didn’t feel any desire after that to build social media presences, because we spotted the con—as did this YouTuber:

Back then, Facebook allowed the importing of articles via RSS, which meant everything from Lucire’s news pages automatically wound up on the social network. It was a crazy idea, when you look back: it wasn’t designed to drive traffic to our main site, it only made Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg rich as you spent more time in their walled garden.

Even after we stopped, we still shared headlines to Facebook, thinking that these would entice fans sufficiently to click through. At one stage, we could see referrals from Facebook among our stats, but these days, there is no correlation between the Facebook reach numbers and the actual views of the story on our own site.

In 2016, NPR posted a headline to its Facebook page, ‘Why Doesn’t America Read Anymore?’ but the contents of the article read, ‘We sometimes get the sense that some people are commenting on NPR stories that they haven’t actually read. If you are reading this, please like this post and do not comment on it. Then let’s see what people have to say about this “story.”’ You can predict what happened: the link got plenty of comments. Anyone who says that Americans don’t get irony is gravely mistaken.

Even in the late 2000s I was saying we lived in a ‘headline culture’ where people might never read the article itself, and social media have exacerbated this phenomenon. Many social media today, including the largest sites, are little more than glorified Digg sites, places where links are shared, but not necessarily places which drive traffic.

Of course there will be exceptions to the rule, but generally, social media do not mean engagement. A 2015 study by Parse.ly showed that social media-referred readers engage the least with a given article. Search engine-referred readers were slightly better. But the best came from those who were already loyal readers on the site.

In an age of “fake news” I do not believe the statistics will have improved, particularly on websites whose businesses thrive on outrage. People are divided into tribes where they seem to derive some reward for posting more links that support that aims of those tribes: a situation rife for exploitation, if certain countries’ investigations are to be believed. Certainly as early as 2014 I was warning of a ‘bot epidemic’, something that only became mainstream news in 2018 with The Observer’s exposé about Cambridge Analytica.

But none of that bad news broke the addictions many people have to these websites. On our ‘about’ page on Facebook, we note: ‘Fast forward to (nearly) the dawn of the 2020s. We won’t lie to you: we’re not fans of how Facebook says one thing and does another. In our pages, we’ve promoted based on merit, and Facebook wouldn’t actually pass muster if it was a fashion label.

‘We know Facebook is tracking you, often more than your settings have allowed. Therefore, we’re consciously trying to limit the time you spend on this website.

‘However, we also know that we should maintain a Facebook presence, as there are many of you who want that convenience.’

Nonetheless, I regularly wonder if that convenience is even worth it if there is no correlation with readership.

Twice this month I was locked out of Facebook, because, allegedly, there was unusual activity. If checking your Facebook on a far less regular basis—say a couple of times a week—is unusual, then I’ll expect to get locked out far more frequently. As the importing of our Tweets to Facebook is driven by another program (on IFTTT), and that is linked to my personal account (one that I haven’t updated since 2017), then each time Facebook blocks me, it breaks the process. It’s also a website that has bugs that were present when I was a regular user in the late 2000s through to the mid-2010s, including ones where we cannot even share Lucire links because the site automatically ruins the address, rendering the previews anywhere from inaccurate (claiming the page doesn’t exist) to useless (taking you to a 404). Only the text link will work.

We get the occasional like and share from our Facebook, although these do not inform our editorial decisions.

We won’t go so far as to proclaim the end of social media, regardless of how angry the US president gets with fact checks; but we’ve been sceptical about their worth for publishers for a long time, and there are increasing days where I wonder whether I’ll even bother reconnecting the sharing mechanism from Twitter to Facebook if Facebook breaks it again. The question I’m really asking is: does the presence of links to our articles matter much to you?

Ultimately, I care about all our readers, including Facebook users, and that remains the overriding motive to reconnect things one more time after Facebook locks me out. And I suppose the lock-outs in 2020 are much better than the ones during most of the 2010s, where Facebook forced you to download a “malware scanner” on false pretences, planting hidden software with unclear purposes on to millions of computers around the world. Their record is truly appalling, and if Facebook vanished overnight, I wouldn’t shed a tear.—Jack Yan, Publisher