There goes 20 years. Normally when we celebrate a birthday, we do what most magazines do: there’s a story on our founding, some of our best covers, and a nod to the past. I’ll be right up front: despite having thoughts of doing all of that, we haven’t planned anything for this particular day, October 20, 2017, to mark the 20th anniversary of Lucire.

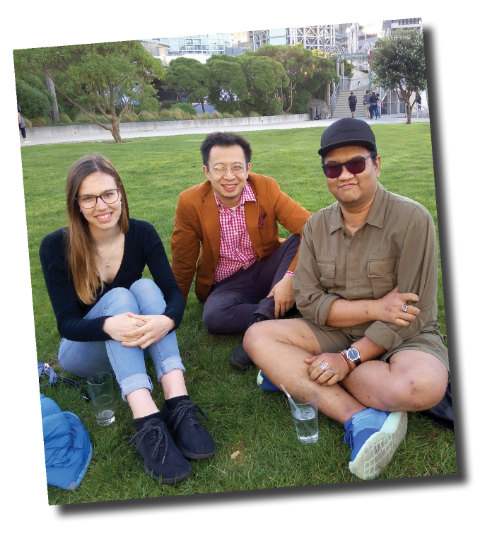

We will have a few nods in the next print issue, and of course we’ve run a few of our favourite pieces online over the last ten months, but even there we’ve been inconsistent. Our desire’s just to keep working on reporting and creating, and it was only Monday when I messaged our fashion ed., Sopheak Seng, and asked if we should go for a drink this Friday.

Above: From Rebecca Taylor’s autumn–winter 2003–4 range. Lucire had attended her first show as aprt of Gen Art some years before this. Top: Lucire covers from around the world.

Our next print issue won’t be a massive historical number. What we instead want to do is look at the future of fashion, something we’ve done with varying success over the last two decades. Lucire was ahead of its time when it launched 20 years ago, and for much of the first five years we introduced, for many readers, names such as Zac Posen and Rebecca Taylor. We broke stories on various labels and retailers before our competitors. And we even got paid by Condé Nast (via an agency) to run ads for some website called Style.com, which we could have previously sworn was flogging clothes from Express Fashion. It was fun being on the cutting edge, exploring technologies, and believing that the world would unite as humans, after all, aren’t that different around the planet. A global generation had sprung up, or so I thought.

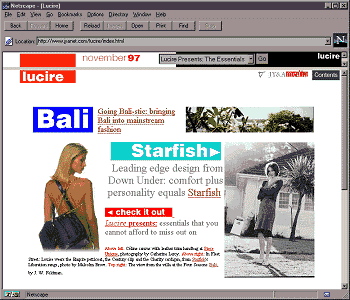

When I created Lucire the world was still very much print-focused when it came to fashion magazines. We adopted a print æsthetic in our online layouts. This might shock many of you, but my personal dream when I started in this business in the 1980s, 10 years before Lucire, wasn’t to report on fashion, it was to be the art director of a fashion magazine. When Lucire became a print magazine in 2004 (which a colleague at Condé Nast told WWD was no surprise, given that we always looked like a print magazine online), a venture that never found the level of success I anticipated, it was very much a fulfilment of that. But in the first seven years prior to going into print we had found a voice: we had become the first fashion partner of what is now UN Environment, we acted as a lightning-rod for new talent, and we dealt with what was next. We mixed unknown labels with famous ones in our shoots—a no-no once upon a time. We felt that Karl Lagerfeld collaborating with H&M was the way of the future: that regardless of what you could afford, you deserved nice design. It was about ‘accessible luxury’.

What happened next has never really been told properly. And here’s where I will go back in time.

Lucire won awards when it became a print title. We were fêted by our colleagues. But we also attracted more than our share of dodgy types who saw a nascent title as a way to further their own agenda. A New York designer asked for print magazines for goody bags and promised to pay for shipping—then gave a fake FedEx number so we got stung with the bill. The server got hacked and someone pumped through gigabytes of traffic, which we had to pay for over many months—even though we believed our web host then should have caught it and nipped it in the bud. We had issues internally with our own team, which is what happens when a sociopath sneaks inside. One editor attended New York Fashion Week and was never seen again. We posted a loss. We looked at ways of upping sales in our home country, in a market that really didn’t care if foreigners owned the competition: they liked their offerings more and voted with their dollars. Media buyers never budged from the establishment and we were pressured to become more like them—inward-looking with more shopping pages. It was hard slog. The memo that New Zealand was the home of The Lord of the Rings and other international films hadn’t arrived at the traditional agencies, who refused to believe that New Zealanders could create something world-class. They hadn’t even figured out in 2005 how to integrate online with old media. It didn’t matter to these people that Lucire was the first international magazine to publish a sustainable style editorial, or that we were targeting carbon neutrality. We were constantly asked, ‘What’s carbon neutral?’ Back then, I felt like Eddie Albert’s Oliver Douglas in Green Acres when I went to Auckland. The mid-2000s were the dark ages, with none of the optimism of pre-bust northern California.

The website was one place where things still ticked along, even if the beginning of 2006 was mired with difficulty and we took our eye off the ball there to make sure the print magazine worked in its home country. The reality in the mid-2000s was that the world hadn’t united, many people who bought print magazines still wanted to read about things that concerned them only domestically. Taking web principles, where readers wanted to get a global view on things, into a print format proved to be unappealing—at least in New Zealand. We as a people then were fixed on looking inwardly when it came to fashion, consuming magazines as catalogues rather than sources of knowledge and inspiration.

We found some incredible and loyal print readers, but never the numbers I expected. It became apparent our readers were the early adopters of any cycle, those who cared about gaining an advantage over others, wanting more information and journeying the globe with us each issue. But as any marketing graduate will tell you, early adopters are a minority. Adventurous people will always be outnumbered by followers, otherwise we would never have leaders in human endeavours. I forgot the lesson that you could never get poor underestimating the intelligence of the public, which is why trashy weeklies sell 20 times more than what I projected for Lucire. But I wasn’t interested in treating people like dummies. I don’t in real life, and I wouldn’t in publishing. People, I insisted, wanted to reach for the next higher goal, like a school pupil in the primers looking at the bigger books that the kids in higher years were reading, wanting to achieve. Additionally, we had a role as a corporate citizen to be socially responsible. That was admirable, but it wasn’t a way to be sustainable in the market-place of the mid-2000s.

There were fewer such issues when we licensed Lucire out to Romania and (as Twinpalms Lucire) Thailand; even our Qatar and Bahrain ventures, however short-lived, hatched some decent product. On international trips I pick up magazines from all sorts of publishers and I enjoy the depth of coverage and attractive layouts. Every year I see titles that mirror elements of what we tried to achieve, be they local titles like Brummell or something as substantial as Monocle, which does succeed at pushing a single product worldwide. My belief that a title could be launched from New Zealand hasn’t completely gone, but the economies of scale were against us: 20,000 copies in a population of four million was a hard ask without budgets bigger than what I could afford. We might have been too early in terms of expecting a globalized audience (it now exists, to wit how major newspaper sites now target international readers), and if we were to do it again in 2017 it might still be a hard copy, but more customized and revolutionary. The print edition has continued, but it is more a luxury product today, a soft-cover coffee-table book in some ways, taking a lead from what Miguel Kirjon accomplished with Twinpalms Lucire.

There were fewer such issues when we licensed Lucire out to Romania and (as Twinpalms Lucire) Thailand; even our Qatar and Bahrain ventures, however short-lived, hatched some decent product. On international trips I pick up magazines from all sorts of publishers and I enjoy the depth of coverage and attractive layouts. Every year I see titles that mirror elements of what we tried to achieve, be they local titles like Brummell or something as substantial as Monocle, which does succeed at pushing a single product worldwide. My belief that a title could be launched from New Zealand hasn’t completely gone, but the economies of scale were against us: 20,000 copies in a population of four million was a hard ask without budgets bigger than what I could afford. We might have been too early in terms of expecting a globalized audience (it now exists, to wit how major newspaper sites now target international readers), and if we were to do it again in 2017 it might still be a hard copy, but more customized and revolutionary. The print edition has continued, but it is more a luxury product today, a soft-cover coffee-table book in some ways, taking a lead from what Miguel Kirjon accomplished with Twinpalms Lucire.

What puzzled me was the feedback from our own compatriots: ‘I always thought you were a foreign magazine, that you licensed and brought to New Zealand,’ and ‘It looks very international,’ or ‘It looks very European.’ Yet everything about Lucire was New Zealand. Run here, designed here. We looked at a lot of local designers. The typefaces were all-Kiwi at one point, and no one was doing that. But apparently, it looked foreign. I took that to mean that it looked too good to be local. Ten years ago, it seemed that we didn’t have a high opinion of what we could, as a people, achieve, despite winning all those Oscars with Sir Peter Jackson’s films. I hope we think differently now.

We came out of that difficult patch. Certain people were replaced as we restructured, and we became more wary of opportunists who wanted to use Lucire for their own gain exclusively. We were no longer losing money. Everyone who contributes today does so as a real part of the team. We struck a better balance between online and print media. We went through a few years of running video content that not many had. I often remark jokingly—yet it is based entirely on fact—that whenever we mentioned Cheryl Cole our traffic would rise. Or Kate Middleton. Or HRH Princess Madeleine of Sweden. Then, the rest of the world caught up and plenty now run the same content, because content wants to be disseminated through whatever means possible. It is only right that people, individuals or magazines, indulge healthy, creative passions, including being their own publishers. Goodness knows I have enjoyed it for decades and others deserve the same sense of fulfilment. It meant, however, that merely mentioning celebrities wouldn’t result in a traffic hit.

But where we have a distinct competitive advantage, is the make-up of our team. Our long-serving editors such as Sopheak, Stanley Moss, Elyse Glickman, Lola Cristall, and many others on our team, are passionate, and it shows. Jo Gair has helped made the print issues more beautiful than they have been for some time, and we know we can depend on our editor-at-large Summer Rayne Oakes or our newer editors Jamie Dorman and Cecilia Xu. They speak with their individual voices here, but there is something that unifies them all. It is our culture, our desire to make the world a better place, and an innate curiosity to explore the world and share it with others.

The crew in Bahrain at Lucire Arabia came up with the slogan, ‘Independent, intelligent, inspirational,’ even if I probably uttered those words in our original Skype meetings. The fact it took a licensee to craft this says something about how busy we all got internally (we started off as quarterly, then monthly, then fortnightly, then weekly, and now we’re virtually daily here on the web) to recognize that this is what makes us special. The same could be said for the amazing talents who create the shoots in our print edition. Their output is astonishing and we are always proud to share it, and humbled they continue to work with us.

Amanda Satterthwaite

Above: Quick drinks after work on a Friday to mark two decades of Lucire: new writer Sarah Arnold-Hall, publisher and founder Jack Yan, and fashion and beauty editor Sopheak Seng.

The world is now different than it was in 1997. Then, Google did not exist. Lucire was one of the survivors of the dot-com bust, and we even had our content licensed by Altavista, the biggest search engine in the world (once upon a time). Today, content producers are dependent on Google News, a site that cares little for independents and puts the establishment first. It’s a sorry state of affairs that big firms have consolidated their power, with some even calling for a two-speed internet, which disadvantages independent voices. It’s the opposite of the internet that emerged at the time Lucire was founded, which was to serve the many rather than the few. (It’s also the opposite of what Google once stood for when they appeared on the scene one year after us.)

If there’s any lesson as we turn 20, it’s to keep fighting the same forces that seek to work against people and their self-interest. Once the web was a haven from those greedy tendencies that existed in the real world. Now we have to take the same fight online to keep the ideals alive. It is a fight that must, by necessity, have Google and Facebook in its sights as they seek to intrude on individual privacy and slant the ’net toward the biggest players, silencing diversity.

There’s still a lot about Lucire in 1997 that applies in 2017: that we should be about the next thing, that all people deserve good design, and that we should talk to you as intelligent human beings. I believe now we are looking for depth again, giving a voice that no one else can. How we navigate and succeed in this late-2010s market will be dependent on how we earn your support. And we’re keen to do that as we begin our 21st year.—Jack Yan, Publisher