Sanja Bucko

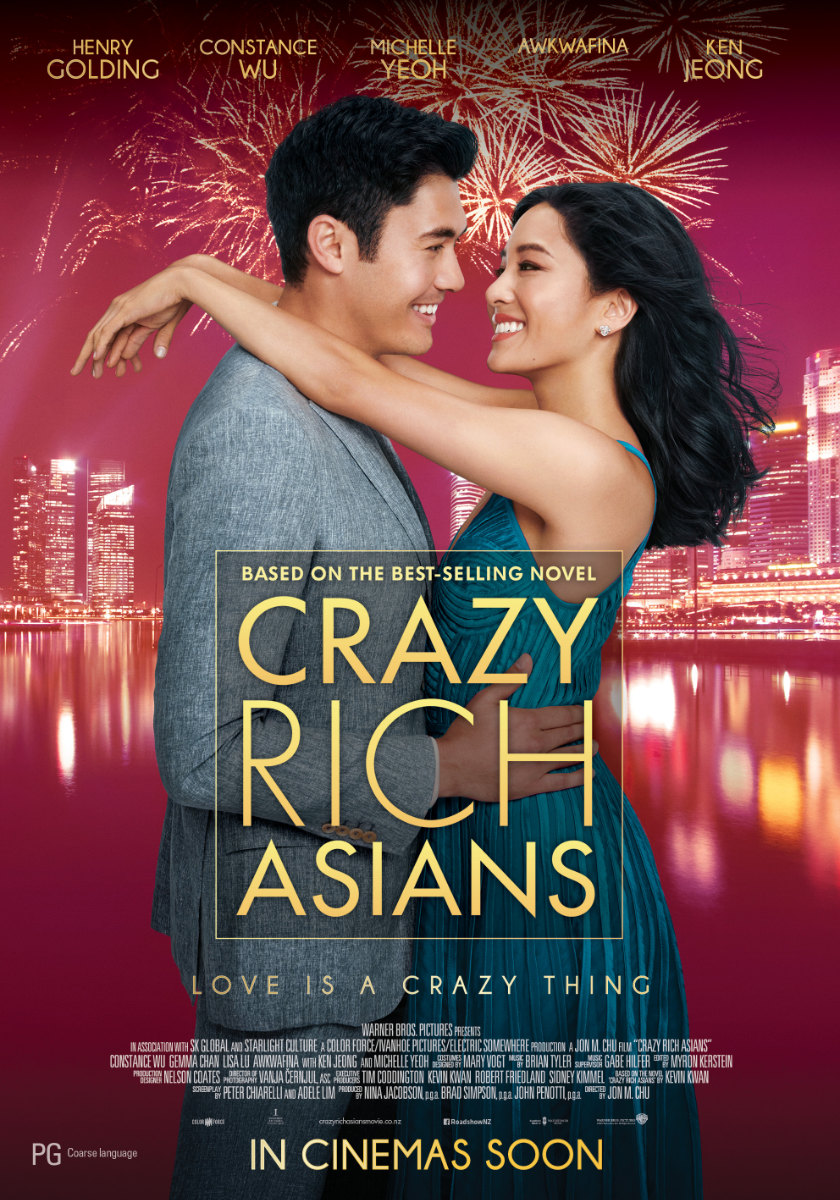

From top: Michelle Yeoh, Henry Golding and Constance Wu in Crazy Rich Asians. Henry Golding and Constance Wu. Lisa Lu’s Ah Ma character meets Constance Wu’s Rachel Chu.

What a pleasure it was to see, finally, Crazy Rich Asians, which opens here next week. It’s already been doing very well in the US, beating the New Zealand-filmed The Meg, which itself has Chinese actors (and Chinese money, incidentally) behind it. Predictions are that Crazy Rich Asians will see another US$25 million this weekend, following the US$26 million of its début weekend (see video at the end of this story).

It’s a pleasant enough tale: a rom-com romp set in NYC (for a short while), Singapore and Malaysia. As someone of Chinese extraction, what a pleasure it is to see Hollywood have another film with a majority-east-Asian cast, 25 years after The Joy Luck Club. We’re a demographic that’s massively under-served, yet judging by how east Asians have flocked to this movie, you have to wonder why, since it obviously makes financial sense. Like Snakes on a Plane a decade ago—a film with which this magazine has a behind-the-scenes connection—the title makes it pretty clear what the film’s about, and that’s enough to entice many of us along, even if it was far from a full house at the Penthouse in Brooklyn yesterday.

Those of us in the diaspora don’t have many cinematic experiences like this, and as my other half and I exited the cinema yesterday, I remarked how important it would be for a young person to see their own race represented on screen. You feel your stories are being told, and you’re not an “other” any more. On that note I completely empathize with women who are being slightly better represented in film, such as Star Wars, and being cast in roles once held by men in remakes, Doctor Who perhaps being the most notable this year.

Crazy Rich Asians works in enough Chinese culture for it to be relevant to us and be understood by the mainstream: remarks about not needing to thank family, for instance, a reference to physiognomy, another to lucky colours, and a stereotype about foreigners sticking their elderly in rest homes all resonated.

And it’s certainly true how some overseas Chinese are perceived as bananas, and that we divide our own lot just as well as, say, certain Brits might look down, or at least a little oddly, at their colonial cousins. Constance Wu gives a great performance as the Chinese American, with the cultural issues coming on top of the nervousness of meeting her character’s boyfriend’s family. We’re expected to believe that an economics professor hasn’t online-stalked her boyfriend after a year to find out about him, but then the story wouldn’t work if she had.

In among all the good this film is doing, it’s disappointing to see some go after leading man Henry Golding for being Eurasian, when he himself identifies with his Asian side, and has spent more years in Asia than anywhere else. A parallel was drawn by one writer with Barack Obama: if we didn’t have a problem with him identifying with black, then why should we have any issue with Golding identifying as Chinese Malaysian? My only real complaint was the interchange ’twixt Cantonese and Mandarin among the same family members, which stems partly from my not understanding much of the latter (for those who don’t know, it’s like an Italian trying to understand a Dane. They might both use Latin characters, and some things are recognizable, but generally you need to be schooled in both to understand both). But then, you think, it’s just nice to hear your own language spoken (thank you, Michelle Yeoh), and in the correct setting (and not Cantonese-speaking Mongolians in the remake of Flight of the Phœnix). It doesn’t insult non-Chinese viewers, otherwise you have a sense that someone thinks that a lack of authenticity is OK because it’s principally gwailo who are going to see it.

continued below

Golding gets second billing in the film’s credits, understandably: the story is told from Wu’s character’s viewpoint, and she’s the one that western audiences will identify with. And, to be fair, she’s the bigger star: Golding may have done some film but his CV has a lot of TV hosting. Hence Marlon Brando and Gene Hackman preceded Christopher Reeve in Superman (1978). It’s interesting, then, to see the order reversed on some posters, and certainly the one here, where the male lead gets top billing, but, when it comes to the credits in small type underneath the image, he isn’t mentioned. Even with a film that tries to do right by east Asians, and has a female lead, not everything has been fairly applied.

It’s not a masterclass in film, but it is fun, and director Jon M. Chu understands plenty about the conceit of too-moneyed Chinese in the far east, displaying it on the screen for us to either find vulgar or admire, depending on your slant on such things. It also changes the ending of the Kevin Kwan novel (and omits some subplots for time), lacking its ambiguity, in favour of a happier Hollywood ending. A perfect film, then, for a chilly winter’s weekend, and you leave feeling a bit warmer, and brighter, that in this cinematic world, character and mana win over bank balances.—Jack Yan, Publisher

See our interview with co-star Awkwafina here.

Sanja Bucko

From top: Pierre Png and Gemma Chan. Constance Wu. Dr Ken Jeong, Constance Wu and Awkwafina.