Nicola Edmonds

Stephen A’Court

Garth Badger; make-up by Kiekie Stanners

Hansel & Gretel, the Royal New Zealand Ballet’s newest production, answers an important question: what can be made when you have every creative firing on all cylinders?

Here we have Loughlan Prior (right) with his first full-length ballet, based on the Grimm Brothers’ collected story, with his outstanding vision, wonderful pacing and choreography; Claire Cowan composing an original score that underlines her versatility; and award-winning designer Kate Hawley, an international talent and veteran of blockbuster films whose creativity shone.

Perhaps it should really be called Gretel & Hansel, for it is Kirby Selchow’s character of Gretel who proves the more resourceful (when Gretel is under the Witch’s spell, Selchow performs an excellent solo), while Hansel, attached to his toy rabbit, is played with childlike wonderment by Shaun James Kelly. The two dancers, who have appeared in countless RNZB productions, have come into their own in this one as leads, and it is stronger for their characterizations. The parents, played by Nadia Yanowsky and Joseph Skelton, have an enchanting pas de deux in the first act, when they realize the dire financial situation they face (broom-selling is a tough gig in the 1920s European town in which the ballet is set), yet the romantic dance demonstrates that their love and faith will see them through.

This, and other pieces, emphasize that this is a classical ballet, one which is geared perfectly toward family audiences, with a wide appeal.

Cowan’s newly composed score brings together numerous elements: romantic at times (the aforementioned pas de deux), jazz and Broadway (Act II’s Gingerbread House number with the Witch and gingerbread men), and cinematic (the parents’ emotional search for Gretel and Hansel in Act II). She is the first female composer commissioned to write a full-length score for an RNZB ballet, and one hopes that Cowan’s talents are recognized far more widely than they have been. Cowan helps redress the balance of the few women in her profession, and her work shows that the composing versatility of, say, Aaron Copland, who wrote for ballet and film, is, fortunately, very much still with us.

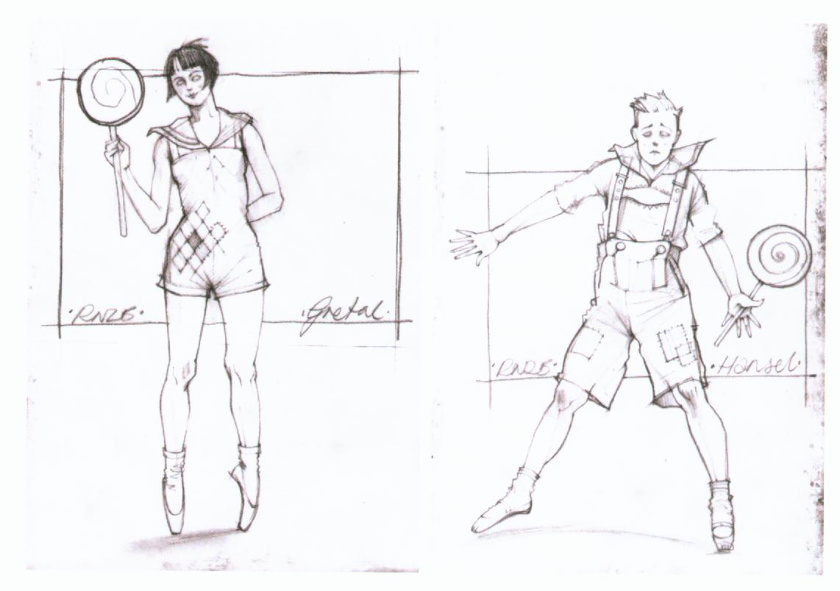

Visually, Hawley—whose credits include costumes for Suicide Squad, Edge of Tomorrow for Christopher McQuarrie and Doug Liman, Liman’s Chaos Walking, Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim, and Chris Sanders’ The Call of the Wild—shines here with her designs. The 1920s’ townsfolk and their black-and-white finery (top hats, fox furs) contrast the grey costumes of Hansel and Gretel and their family. In the forest, Hawley has turned the Dew Fairies into flappers, and the Sand Man (played by the tall ballerino Nathan Mennis) channels Buster Keaton with his costume.

The team brings together numerous references: Méliès’s 1902 science fiction film Le voyage dans la lun is parodied with an ice-cream in place of the spaceship on the moon, working in the food theme; hypnotic circles in the background projection reminded us of pop art and, it must be said, some of Saul Bass’s film work; and the Dew Fairies’ numbers owe a little to Busby Berkeley (not on the same scale) and Million Dollar Mermaid, especially when we saw the Queen of the Dew Fairies, played by Mayu Tanigaito, who executed an impressive sequence of fouettés. The Witch’s transportation is a steampunk bicycle. The Gingerbread House’s components float and join together like an animation; the fact it is like a Tardis—bigger on the inside—is referenced in the notes. The Gingerbread House’s extreme colour (extravagant reds and pinks) and the Witch (Katharine Precourt) had the spectacle of ‘All That Jazz’ in Chicago meets Cabaret. (The ‘Eat Me’ sign is straight Broadway.) When the Witch’s true form is revealed (played by Paul Mathews, who camps it up), it’s out of early horror films. As Prior wrote in his notes, ‘She’s a mash-up: a cabaret performer, Kylie Minogue showgirl meets Leigh Bowery, vampiric Nosferatu.’ Indeed, the gingerbread men, with their hooded costumes, also channelled Bowery.

There are additionally themes of income inequality—there is no middle class in this story, only the impoverished main family, and the richer city folk and private-school students who taunt Gretel and Hansel; of greed and child abduction, as in the Grimms’ tale; and of love (the original story in the Brothers Grimm’s collection did not have a “wicked stepmother”, and this adaptation follows that). What is not explained is the payoff at the end: a happy ending is what we expect (and we get one—not really a spoiler), but what happens to the Witch’s funds that the gingerbread men, presumably free from the spell that kept them subservient, present to the family?

Two years of work went into Hansel & Gretel, and it shows. For those wondering where the RNZB would wind up under artistic director Patricia Barker, and the first year with Lester McGrath as executive director, here is your answer. It’s in a fine place when a creative team can stretch its legs like this. If you can remember their 2010 production of The Nutcracker, you’re coming close—but ramp up the originality more. Ryman Healthcare’s sponsorship has helped make it a reality, along with others. It’s a perfect family ballet for the holiday season, having commenced tonight (November 6), running through December 14. Wellington is its first location, before it tours to Palmerston North, Napier, Christchurch, Invercargill, Dunedin, Auckland and Takapuna. Full details are on the RNZB’s website.—Jack Yan, Publisher

Stephen A’Court

Kate Hawley’s designs for Gretel and Hansel.