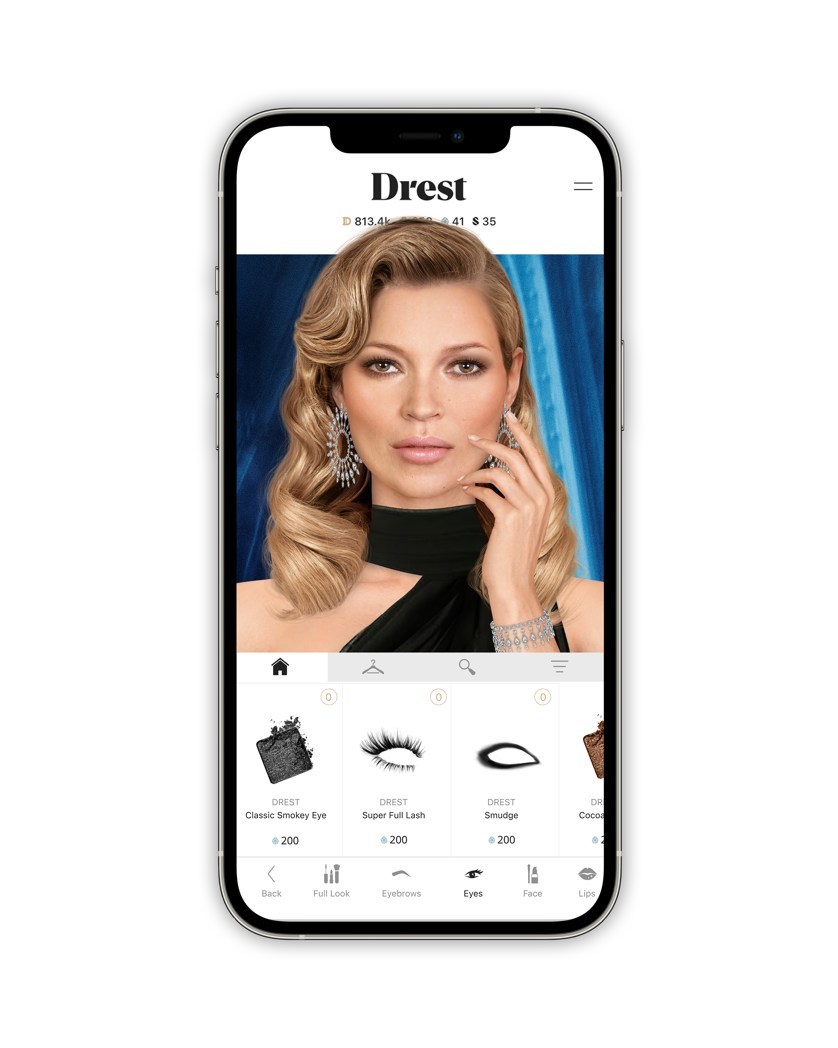

There were three stories in Lucire during March on virtual worlds. First, Riveka Thevendran took us into gaming fashion with a brief journey into its history, for a feature originally published in print. Secondly, DeepBrain announced that Chinese state TV channel CCTV will have an AI anchor. And thirdly, Kate Moss now has an avatar for Drest, the styling game founded by Lucy Yeomans.

I’ve respected Lucy’s work for a long time, and I’ve openly said that Porter inspired the last facelift for Lucire in print back in 2016. When she left Net-à-Porter to start her own digital company, you knew there was a solid reason. Later developments in the metaverse have proven Lucy to be prescient once again.

We’d be naïve to ignore such developments and I think they’ll play a greater part in technology than social media did. Drest, of course, has the great advantage of the brands that support it—major brands like Burberry, Prada and Stella McCartney that we all recognize. Natalia Vodianova and now Kate Moss, among others, have avatars there. Like Tmall in China, it has big-brand support, but unlike Tmall it hasn’t been opened up to as many participants. Drest remains a curated, high-end, and rather exclusive app, something with an analogue in the real-world, high-end, exclusive boutique. Technological democratization is more positive than negative at this point, but it’s not something luxury brands should really pursue in terms of platforms if they want to maintain their lustre. By all means, create technologies that get your brands to as many as you can, but doing it in someone else’s playground can limit you. It might even take you downmarket.

We’ve had years of accessible luxury—the idea that you can buy designer fashion at mass-market prices—a phenomenon popularized by H&M’s designer collaborations. The limited nature of these collections never devalued the designers’ brands themselves. Nearly two decades after the first, with Karl Lagerfeld, the novelty has worn off, and it has become apparent that it became a good way to recycle earlier themes and gain awareness for the genuine article. Like a licensed fragrance, which gives buyers a taste of an upmarket brand, the H&M designer collaborations essentially did the same thing using the medium of clothing.

Drest is something similar—it provides a shop window for the upscale brands, through a game that is free to download—but Drest itself doesn’t devalue its own market positioning. You can’t dress avatar Kate in H&M or Primark. Everything has a premium, real-world counterpart. The brands that are on there are not mixing with the mass market.

With social media, you are mixing. The interface for my personal account is the same as the interface for Lucire’s or anyone else’s. I struggle to see just how these services provide a premium experience. Sure, you can have online shopping within the app. You can post great photographs that scream premium or luxury. But, frankly, I never feel particularly special in Facebook’s or Instagram’s or Tiktok’s walled gardens. I can follow just the luxury brands but that experience is identical to following friends and family. If I buy ads there, not only are the numbers highly dubious, but I can’t offer people an experience that’s any different unless I take them off-site. And do I really want to be on platforms often criticized for hosting racist or fascist content that survives multiple complaints?

This might be why we never placed that much effort into building our social media followings. Individual team members often have more followers than Lucire itself. I once saw some fun and entertainment to having an Instagram account, regularly updated, but for Lucire? We’re in the business of telling stories and while a picture is worth a thousand words, those thousand words don’t fit into an Instagram caption. We can’t do our job on such platforms.

As to Facebook, we once imported our content there via RSS, till we realized no one was leaving Facebook to read Lucire. Rightly, we ended the practice. Having nurtured our Lucire group, Facebook suddenly announced ‘pages’ which, at the time, looked exactly the same. What to grow now? In the end, we couldn’t be bothered with either. Our Facebook page’s feed is automated. We shouldn’t spend any more time than is necessary on something that doesn’t help with our bottom line. Having readers not come to our sites because they’ve already consumed a story on social media is not in our interests, only the interests of the Big Tech platforms.

The 2020s will see brands be far more discerning, careful about how their products touch their consumers. Those experiences need to be special, and as the decade continues I become ever less convinced that Big Tech does that. Drest, however, does, and I expect others will follow.

Jack Yan is founder and publisher of Lucire.

Top image by Andrea Piacquadio/Pexels