Top: In September 2021, Chiara Ferragni was named a Hublot ambassador. With 25 million followers, she’s the exception rather than the rule when it comes to bloggers and influencers. Above: Peak blogger? Elin Kling modelling for H&M in 2011 with her own collection for the Swedish retailer.

There’s a good reason that whenever we do a story on NFTs, it gets very few readers: the virtual world is not as interesting or as colourful when it comes to fashion.

Of course there’s room for the creativity that virtual spaces offer. You can see design students experiment with new creations and test them out on virtual models, for instance. But the real world is always more enriching.

During COVID-19 lockdowns, so many of us craved connections with our friends and wished we could continue travelling. And it’s not just those of us who have become accustomed to it. Children realized that school was a place of social connections and friendships. Experiencing it through a screen is a poor replacement, placed somewhere between reality and having a pen pal.

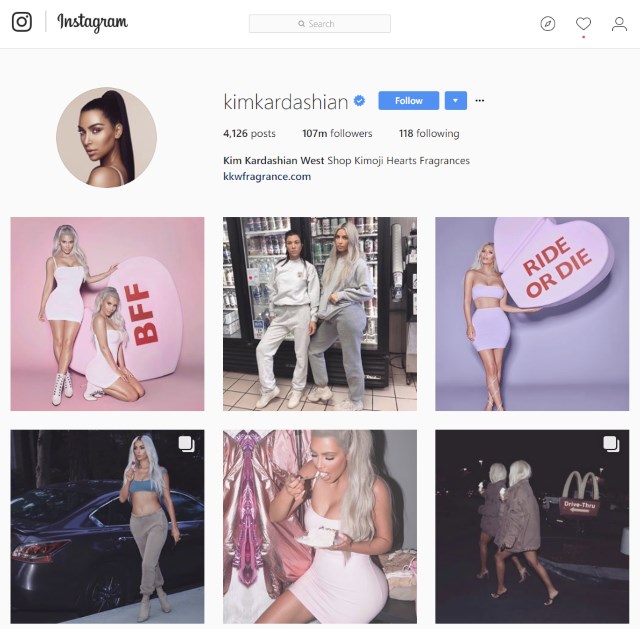

This month, one trade publication wondered whether we have reached peak influencer on social media. On the flip side, The Business of Fashion has done a story wondering whether companies should employ virtual influencers. The timing of these two pieces isn’t coincidental: they are both in the Zeitgeist. With Facebook finally owning up to a drop in user numbers—its app is not even tops among youth—and Instagram getting more filled with suggested posts and advertising, no wonder youth are turning more to the likes of Tiktok. There’s an extra theory: Tiktok has become a place where physical activity, e.g. dance, short video clips, is celebrated—things that virtual actors aren’t yet adept to doing. To the Tiktok generation, there’s more reality there.

We’ve long said that platforms such as Facebook and Instagram are plagued with bots. While no platform is perfect, we’ve filed enough reports over the last 15 years to know that not all are acted upon, and parent company Meta’s record of responding and taking them down has got poorer. So if these are the platforms that companies are still spending on (why?), then there’s probably a case to let a virtual influencer communicate to bots on these platforms and just leave it to them. Nothing will actually get bought or sold. In fact, we’ve seen bot nets at work on Facebook, talking to one another, and fooling Facebook’s own systems.

Peak influencer was probably a few years ago, in our opinion, and now there is an ecosystem of noise, users modelling and promoting items that mean even legitimate posts are advertisements in amongst the advertisements on Instagram, for instance. How does one break free of this?

Like so many things, we’ve witnessed all of this before.

In the 2000s, bloggers were all the rage. They were getting better seats than traditional media in some fashion shows. But where are they now? The word blogger seems dated, a throwback to an earlier generation. They peaked, and they fell when companies realized they didn’t have the cut-through to consumers that they needed. Obviously, there were always exceptions—Chiara Ferragni (still very active on Instagram) and Elin Kling (whose site is now gone)—but they were never the norm. You can sell opinion, and you can even sell snark—up to a point.

Even web media were once novelties—we recall a competitor’s column, ‘Chic Happens’, which took on a life of its own. Its gossip authors were fêted by the New York fashion industry at the turn of the century. Hint, the brilliant web magazine helmed by Lee Carter, was a perfect place for the column, thanks to smart design and an understanding of the medium. While Hint continues, ‘Chic Happens’ is another throwback to an earlier generation.

Fashion labels really need to re-evaluate how they promote, and it must involve real-world experiences and real-world media. Fashion shows are not necessarily big-budget affairs: they can be intimate gatherings of existing clients. For new labels, friends will be the first promoters. Of course, they will use social media as well to tell their friends, but at least this isn’t done at a level that almost feels automated. If a regular Instagram user posts about her daily life, then it’s going to be quite special when she posts about an event she attended. It’s all the more real. Contrast this to an influencer where every post is promotional, or shot at a beach or some holiday spot.

You want a genuine story told by people who are enthusiastic about what you do.

Fashion media, big and small, help tell the story, too. What better than something written up by a professional, letting the story have its own life with angles that you might not have foreseen? Or hiring a public relations’ expert who knows enough people who will love your work. Advertising, of course, will get you even further when it comes to visibility. Its role, as us advertising guru Bob Hoffman puts it, is to make a brand famous.

Hoffman himself writes of the top brands such as Apple and Nike: ‘The main advertising influence on their success is fame. As you’ll see, I believe the most probable driver of brand success—and the central principle of communication that we advertisers can control—is fame. Not brand meaning, or relationship building, or brand purpose or any of the other fantasies that the advertising and marketing industry has concocted.’ He cites other examples, e.g. why some actors can get seven-figure sums (or more) in movies while others of equal talent get nothing?

And getting fame for a brand in amongst a sea of influencers, human or virtual, is not a very prudent game.

Not everyone can afford advertising, but if you’re in the right industry, there is joy to doing something meaningful, or making something wonderful. If others talk about it—that could generate fame. We’re not talking about something happening viral overnight, but a constant, sustained, long-term effort on making good things that others will value, cherish, or spread the word about. You don’t need influencers for that, just believable parties that others have real engagement with. And again we come back to individuals or fashion media, or pr professionals who aren’t reliant solely on influencers. Many of our story leads come from PR firms.

Sometimes, it’ll pique the interest of someone who can make your brand viral. Barack Obama was a senator only known by some—till actor George Clooney publicly mentioned him during the US Democratic primaries in 2007. All of a sudden, Hillary Clinton was no longer the anointed front-runner.

Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, rode the wave of a TV show that helped cement a reputation that he had been building for decades before.

Other times, those magic moments might not happen. But if you are doing something you love, should it matter, as long as it’s sustaining you and your family, and brings you joy?

It’s only right to get word out and be proud of what you create. But it must be prudential. We had our Zeitgeist column on the fall of the influencer many years ago. We’ve seen little to convince us that things have changed. Sometimes you need to go back to tried-and-trusted methods that have worked for far longer than fleeting phenomena. •

Jack Yan is founder and publisher of Lucire.